Learning ‘how to be gay’ as David Halperin* puts it, is a central theme of much gay fiction. Gay novels often stage pedagogical relationships between a gay man who is ‘older’ (or at least has been gay longer) and a baby gay fresh to the life. These relationships are ways to show both the transmission of an ethic over ‘generations’ of gay men, but also the differences, and ambivalences, between generations, each of which has to be gay (or these days, non-binary, androphilic, etc…) in its own way.

From the friendship between Sutherland and Malone in Dancer from the Dance, in which the queeny older character tries to impart practical knowledge and a detached, wry, campy irony resistance to tragedy to the younger, butcher, more romantic and sincere beginner (this is also the stuff of Jack and Will’s relationship in Will and Grace —Jack [McFarland… Sutherland… queer is a different country!] isn’t older than Will but has been gay longer and otherwise) to the mentorship an Edmund White-type character provides for a younger gay in the contemporary (and I hate to say, bad) novel by Zak Salih, Let’s Get Back to the Party, this is one of our ‘big themes.’

(*for Halperin ‘how to be gay’ means, ‘how to watch old movies and get sentimental when Adele comes on at the bathhouse in Hanoi—now I love screen queens, non-Adele divas, and Asians, but this is maybe not the most capacious or accurate definition of gay life?)

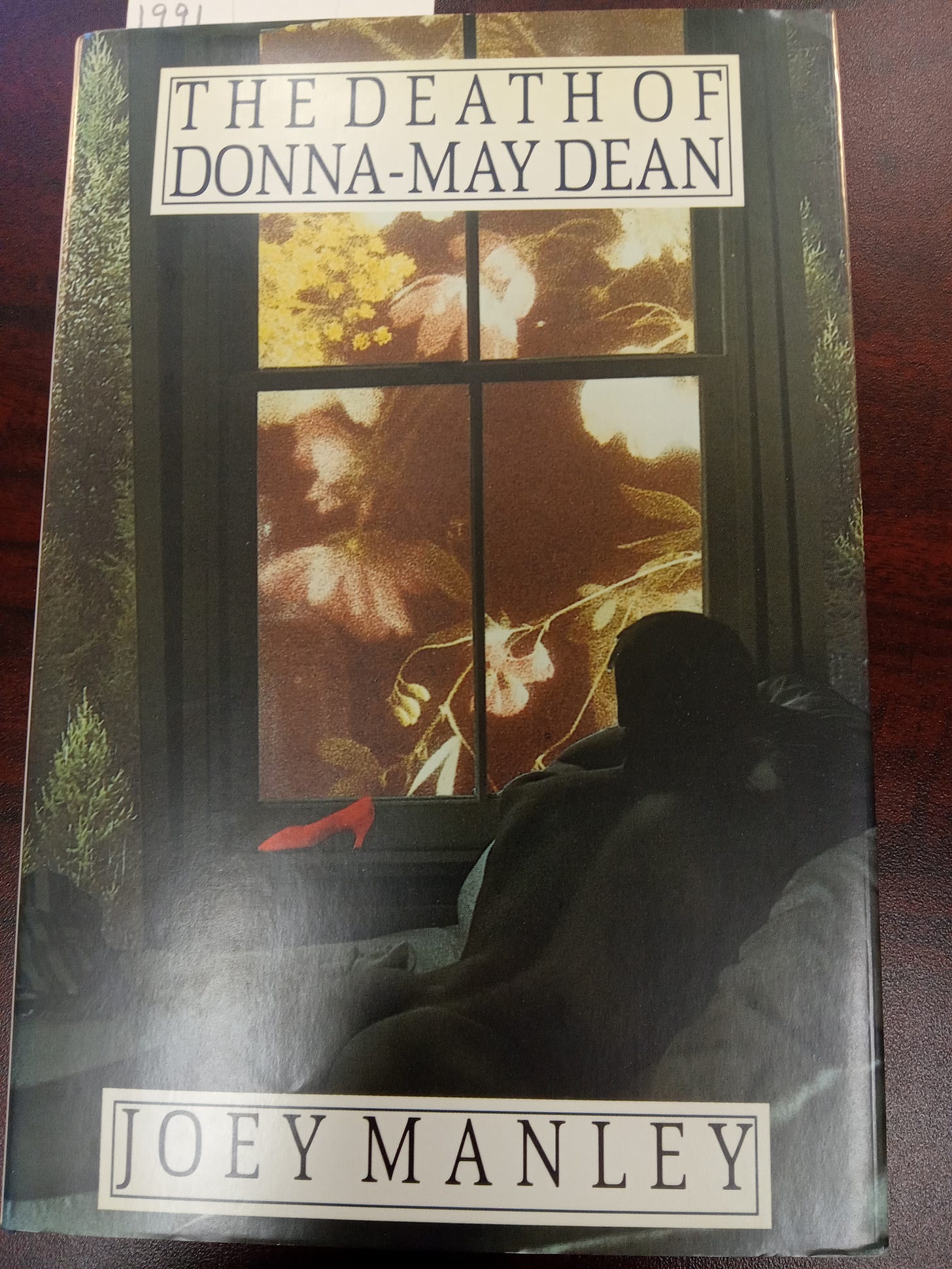

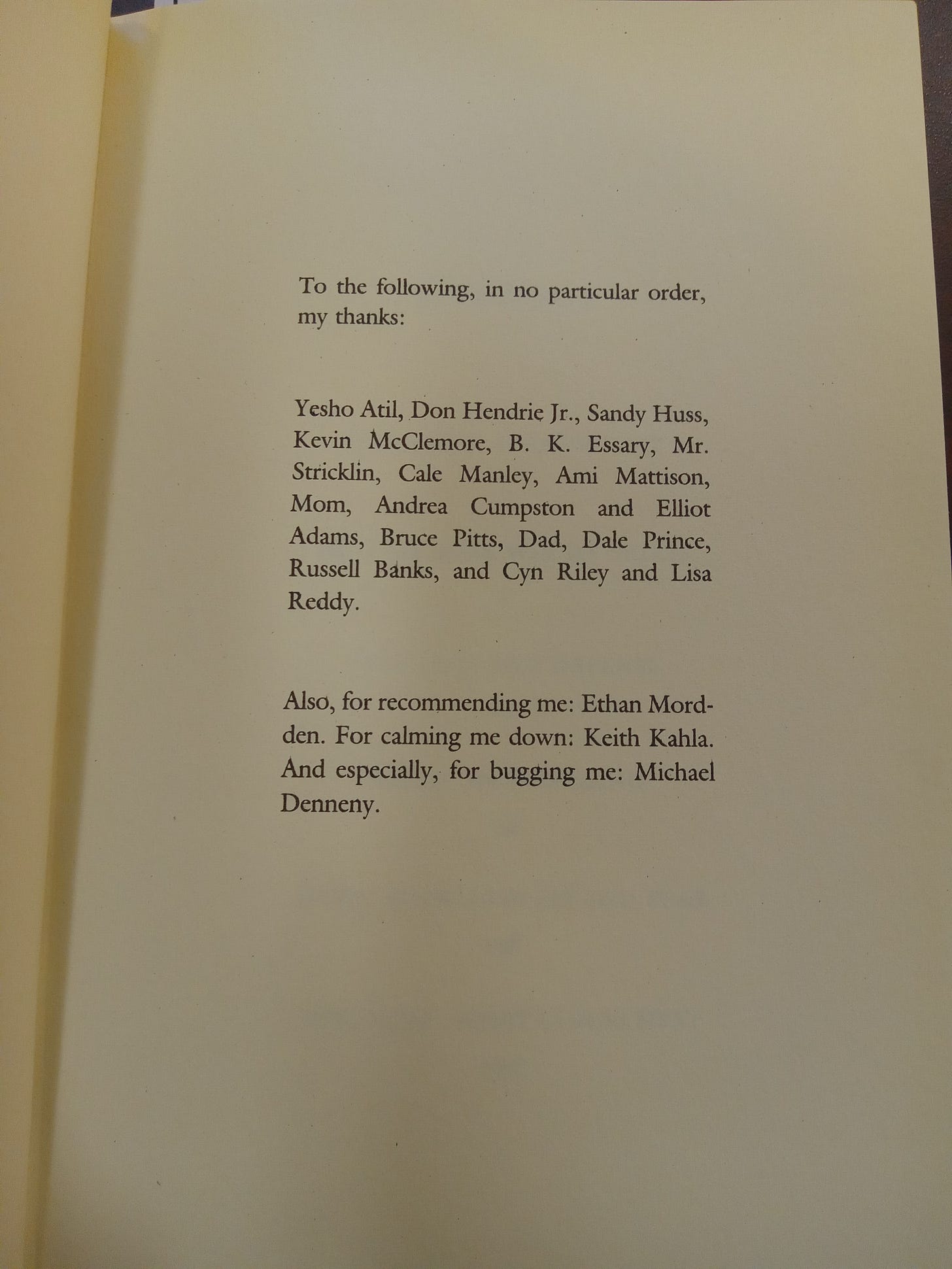

The Death of Donna-May Dean (1991), by the Alabaman Joey Manley (1965-2013) is one of these novels—as well as a ‘Southern’ novel (written while the author was doing an MFA at the University of Alabama) and an ‘AIDS’ novel. Published by Michael Denneny on his gay line at St. Martin’s, it’s a charming but of course imperfect first book. Manley went on to move west, become an early internet comics entrepreneur (developing early subscription services), get quite fat, and die rather young :(

Donna-May is set in a fictional town in northeastern Alabama (‘Genoa’—meaning, I suppose, Florence), a corner of the state that is quite a bit quite whiter than Birmingham and which, from the novel, seems to have a gay life confined to cruising grounds (which double as gay-bashing zones) and house parties—rather as Andrew Holleran portrays the as-far-as-I-know similar rural Florida panhandle.

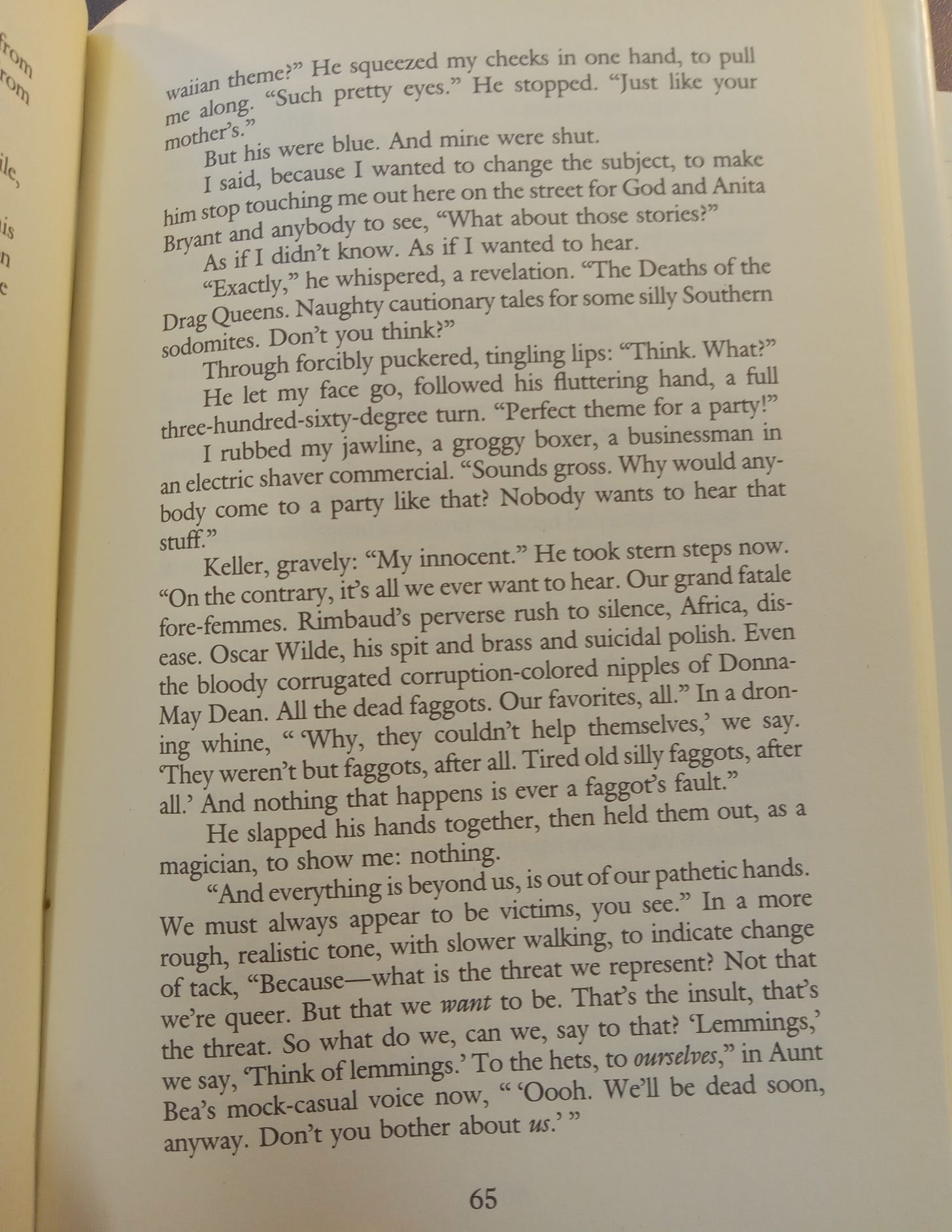

The title character is a drag persona from the 70s who ‘died’ when the queen (Donna-May; out of drag, Keller) who used to do her hung up her heels and settled down with trade. The couple take boys home, and let the protagonist of the novel, whom the former queen picks up at a cruising stop and who is I think just barely legal (?), come live with them. He goes from denying his sexuality to learning the argot and postures of a vanished pansy underworld (playing Miss Lady), which he finds alternately fun and pathetic. He gradually befriends some of the other boys from their circle and starts to develop his own sense of what being gay might mean outside the register of Impossible Doomed Faggotry putting on a brave, rouged face. In that sense, the novel gets at something important and deserves to be better-read, even if as a novel, it doesn’t quite land.

The preface and epilogue both center the theme of intergenerational cultural transmission:

Now, I hate the little. significant. sentences. that end the epilogue. And I don’t love being beaten over the head about the importance of narrative. But I like the titles of the sections, and the resolute-wavering between ‘this has always been our tragedy’ and ‘this is something new and awful; we can also do something new in answer.’ And I like that it works through the sense that gay history is embarrassing as much as it is anything else—the gestures by which yesterday’s queens concealed themselves or brazened it out make us squirm (not least because some part of our personal history, or some potential part of our virtuality, resembles them) no matter how much we either dismiss or celebrate them. And well, those were (as ours are) squirming times!

The novel has some funny sex scenes:

And funeral at the end (Donna-May/Keller dies for real):

While living Keller is the last of the decadents—an A-Reboursian/Yeats-in-Byzantium-ian contempt for nature and luxuriation in our downward spiral, with some half-ironic acknowledgement that this is after all the part we are asked to play:

It’s a bit of Sutherland’s nastier monologues in Dancer—or the queeny tirades that interrupt Cal Yeoman’s plays from the same period—or Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant pleading in court that he couldn’t have solicited trade because no real man ever wants a pansy. What to do with the burden of not only the historical oppression behind such gloomy camp, but with the inheritance of its postures and speeches, is one of our novelist’s big problems—along, of course, with what do about the Happy Pansy, whether dancing on stage on George Chauncey’s 20s-30s New York for the pleasure of the Vanderbilts, or mincing on Youtube for straight women today (not that I don’t love the queens!).

The apparently superannuated but somehow still haunting figures of our historical repertory—doomed queen, giggly pansy, but also the butch clone, the PC activist, whole Village People set, along with contemporary archetypes like the tenderqueer sadsack, the Twitter-posting sex-pig, the PhD who thinks gays need more Adorno and less Deleuze (or vice versa)—how to hold all these as somehow reflections of oneself, without contempt and without indulgence? It’s possible maybe through a kind of political solidarity I find hard to imagine, maybe through a parodic but loving sort of fiction that makes the former imagining less hard.