Since I’m only an hour of traffic away, I took a look at Sontag’s archive at the UCLA library. This includes several dozen diaries that her son David Rieff—instead of burning them, as she probably intended and as a decent person might have done—published in a highly abridged two volumes (depriving the general reader, among other things, of several of her complaints about what a little dumb-dumb he is! For a portrait of his creepy incestuous/vampiric relationship with Mom, see the middle portion of Ed White’s roman-a-clef, Caracole, which is the only entertaining bit of fiction I’ve read by its author and is probably such an effective satire of the pretensions of a would-be intellectual because White himself, having no actual interest in or capacity for ideas except as borrowed items of mental decor, could observe all the more effectively and cruelly the maneuvers of those who use them).

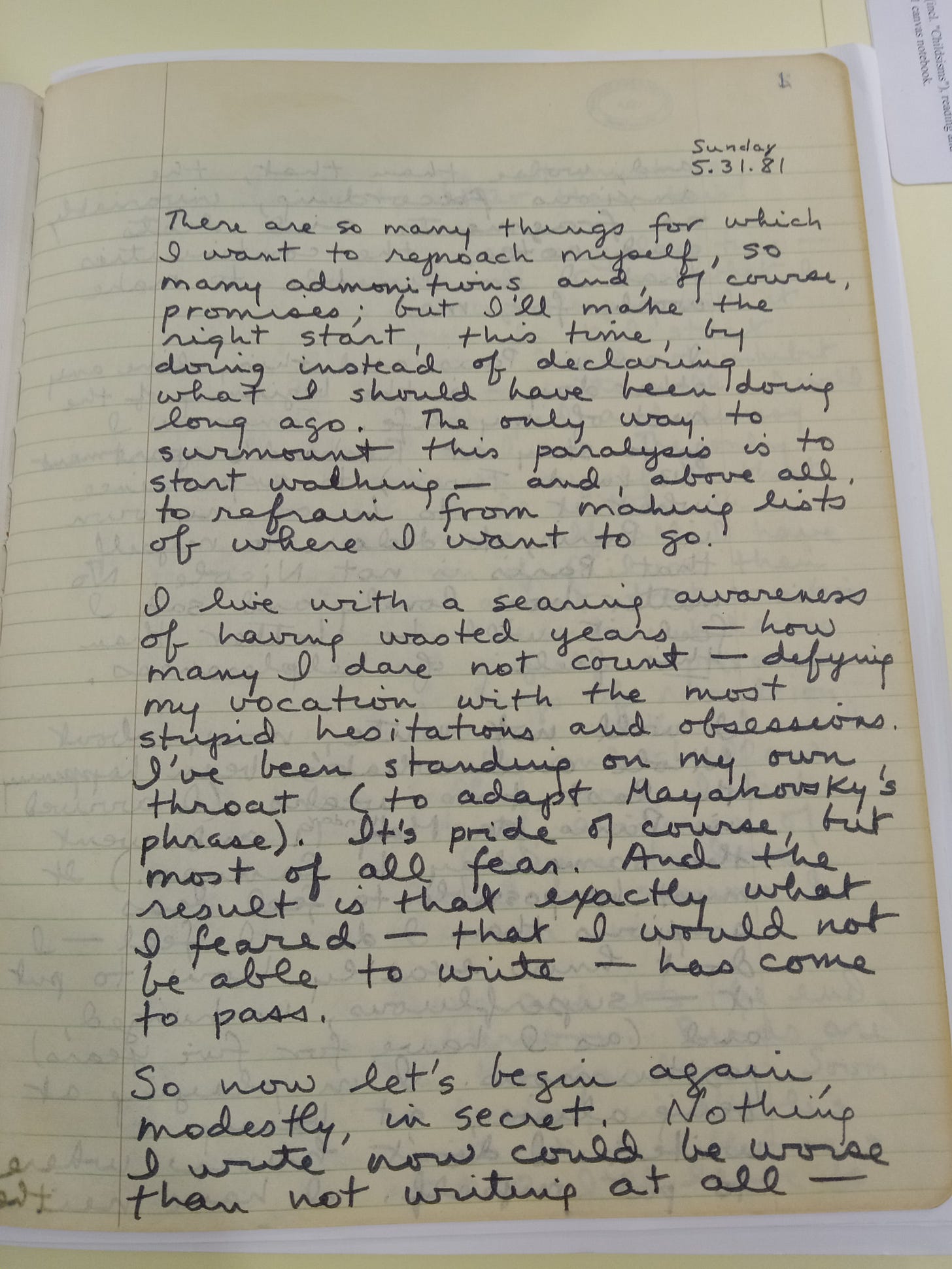

I’d looked at some of Sontag’s diaries from the late 80s and early 90s while working on last year’s essay about her novel The Volcano Lover (which as far as I can tell had zero impact on the public (dis)esteem of that, I must repeat, actually good novel). This time I caught up with her in the mid-70s to late-80s, roughly the period from her getting and writing about cancer to her writing about and not getting AIDS—the period also of some especially self-loathing bouts of not writing, which she… uh writes about and deeper into.

It’s grim stuff. There are some people who keep, Pepys-style, regular accounts of daily goings-on, the happy as well as the sad, and/or who treat the diary as a correspondent who should be entertained (“Dear Diary, you’ll never believe what happened today!”) but a lot of people seem to use diaries to bully (they must think, to better) themselves or to record—as if it would help them understand and thereby escape—their episodes of self-loathing. Sontag wrote almost no fun gossip about contemporaries (we learn that her friend Richard Howard had a “filthy” apartment in Paris, that Howard said Barthes preferred the seedier uptown bathhouses when he visited New York), but lots of lacerating notes urging herself to amend her inadequacies:

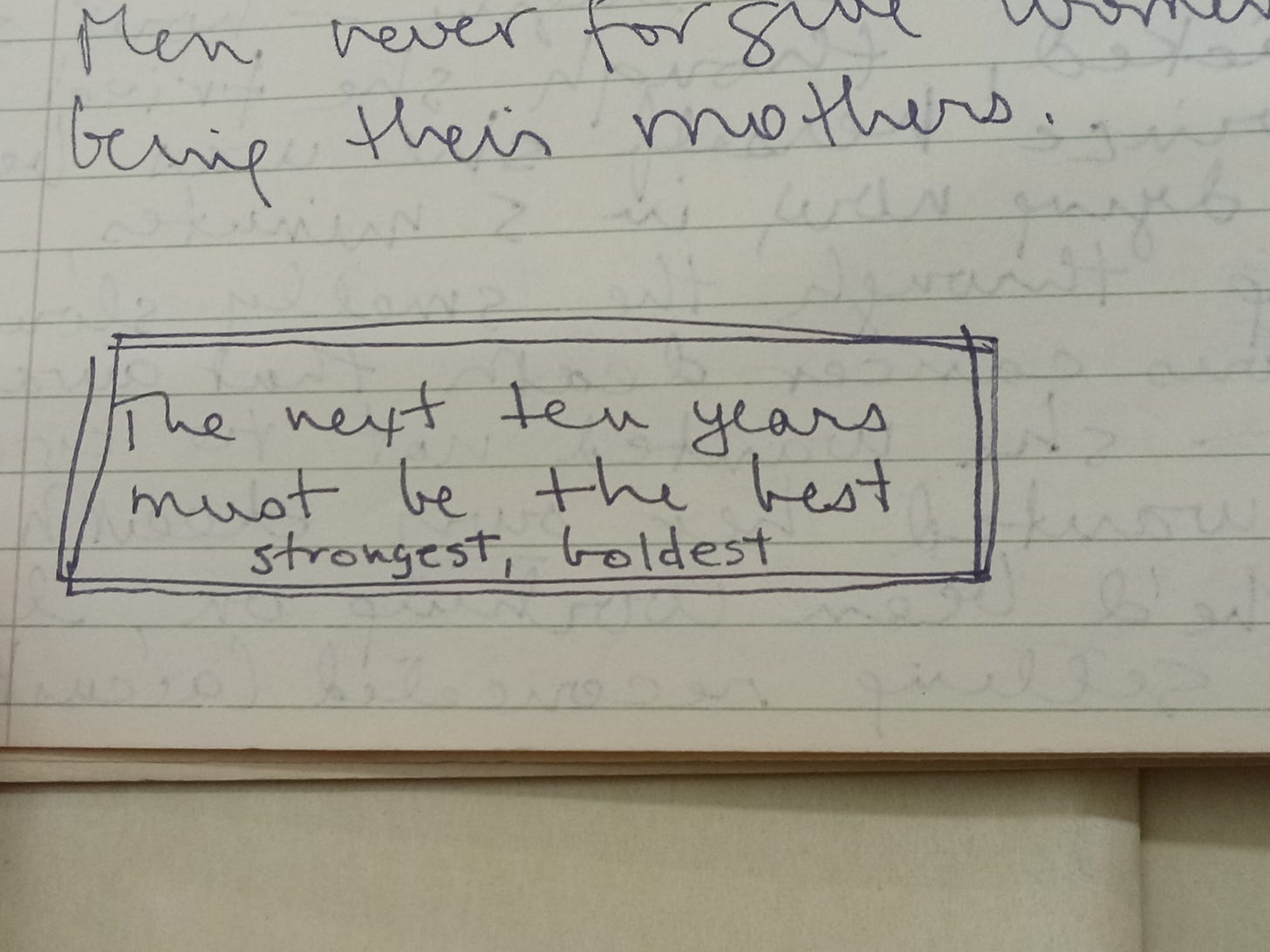

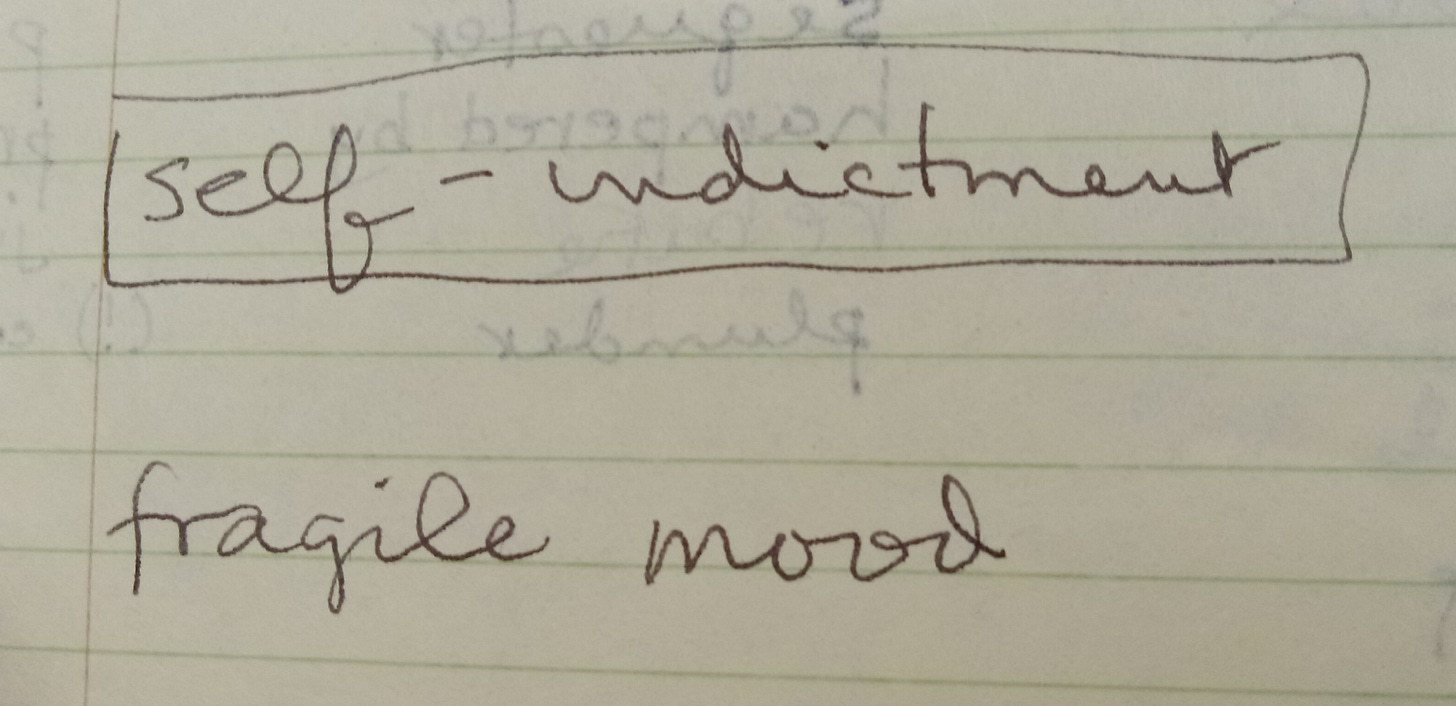

There are short bitter little recriminations in the guise of resolutions, and more extended analyses-attacks:

I feel very sad for her reading such things, and there are a lot of them. As I say in the Tablet essay, there’s something Nietzschean-Nazi about her emphasis on the will to self-creation and genius (I Must Destroy Everything Around Me That Prevents Me From Being the Master), which, like fascism in politics, I don’t think even can be defended on its own terms—that is, it doesn’t succeed; the will gets in its own way. I think her writing might have been less aphoristically constipated, less brusque and pushy in its constantly self-reversing aesthetic and political pronouncements, better able to apprehend the phenomena it was right to be fascinated by (whether Barthes, camp, monster movies, Pedro Paramo) if the writer had unclenched a bit and been a little kinder, if not to all the mediocrity and mental deadness of the world, at least to herself.

But then, I resemble in my own prose many of the things I don’t like about hers, and I’m not sure after all that my wanting to be more self-indulgent, funny, at ease, etc., does anything either to make me a better writer/thinker or (and this isn’t the same thing but neither, I must always remind myself, is it the opposite) to give me the sort of authority and popularity Sontag has among the vast audience of readers who, hating to think (for themselves or for anyone else) love to be bullied and talked down to as if that were an education (the sort of people who pay 300 dollars for NYRB lectures by Merve Emre or Substack courses by Garth Greenwell are I suppose exercising in the domain of letters the sort of masochistic impulses other people get out of their system by shelling out for feet pics from particularly average-looking findoms—people do not want to be free).

Sontag yells at herself until the ideas come. Harold Rosenberg in contrast has an admittedly insane and chauvinist essay arguing against women’s liberation in which he says—making a brief moment of sense in his misogynist delirium which appeared in all places in Vogue (1966)—that like the odalisque waiting boredly in the painting for something to happen, the writer sits in expectant open blankness for thinking to befall (this is not, and indeed is the opposite of, what Andrea Long Chu says about how we’re all women because subjectivity has the shape of sissy porn—firing up porno vids that let you imagine yourself as a non-subject and fetishize your gendered non-subjectivity as ‘female’ is a very agentic, very male activity, and writing up your goonery as vulgarized Theory for the middlebrow readers of N+1 or New York mag is the furthest thing from being surprised by thought like the fisherman’s wife by the randy octopus). It’s not passivity; it’s a playing passive that makes the idea feel in charge. Sitting around in a seductive pose of boredom sighing languidly until at last a thought swoops in to save you. As opposed to berating yourself to rev up your essayistic will.

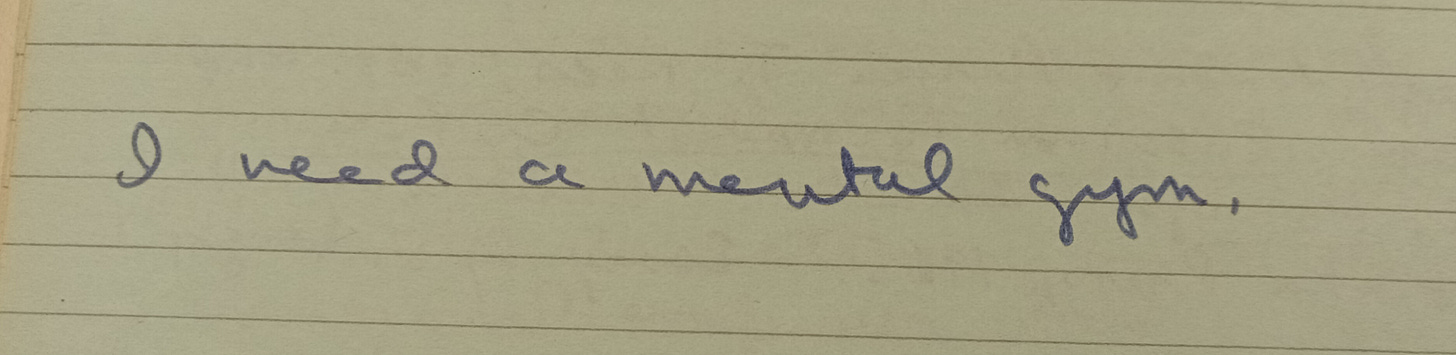

But maybe writers don’t have much control over the personae they adopt to get themselves thinking, or coax thought towards them. Chu has to imagine herself hypnotized; Rosenberg pictures himself as a coy harem girl in the Topkapi of thought; Sontag’s got a membership at the “mental gym.” All these scenarios sound, to me, pretty awful—but then again, all these people, even Chu, are doing better than me, careerwise! Maybe I haven’t yet found the exact fantasy I need to get off.

Btw one of Sontag’s shrill notes to herself—the very opposite of my mom putting '“I love you! Have a great day” on a post-it in my lunch box—goes, tragically/hilariously:

It didn’t work.

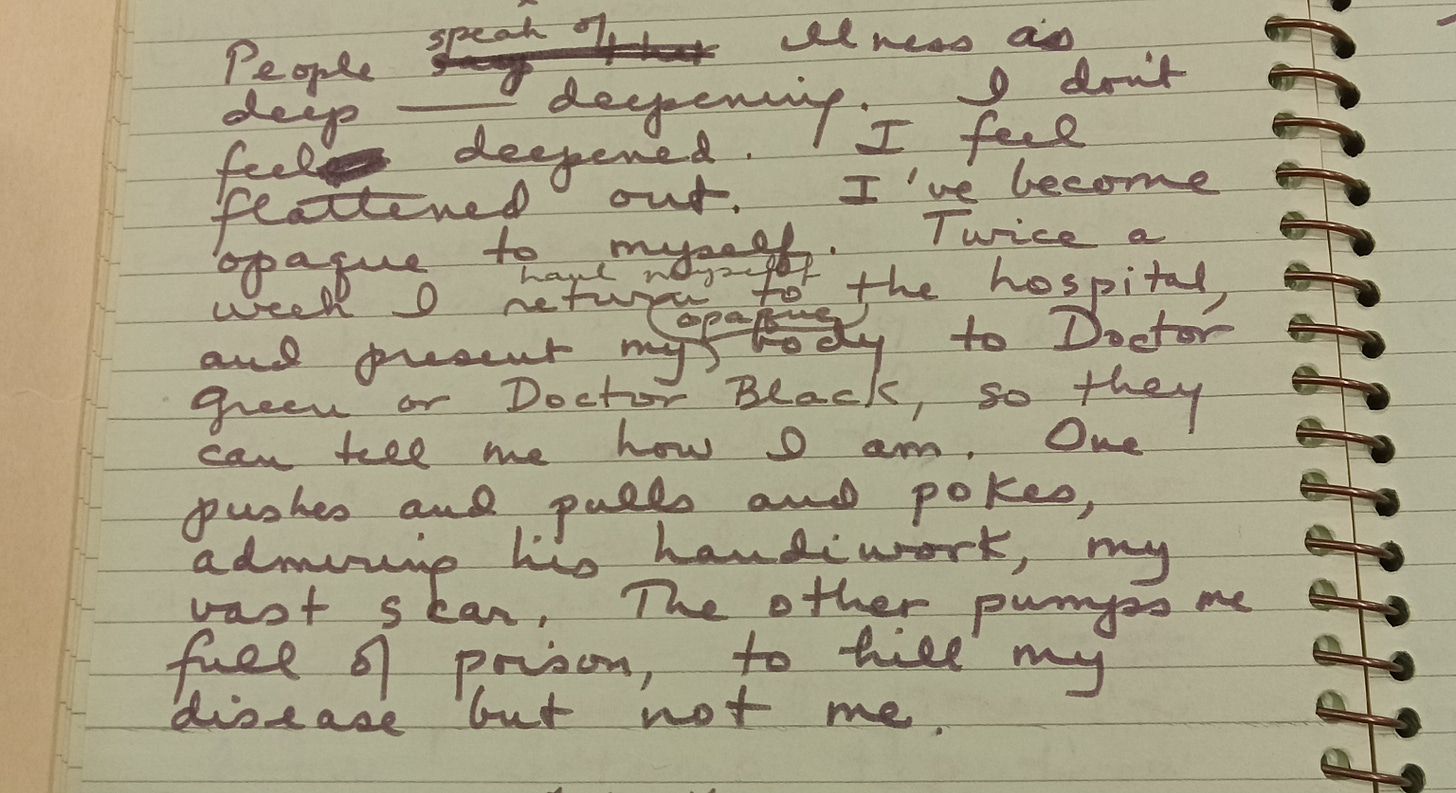

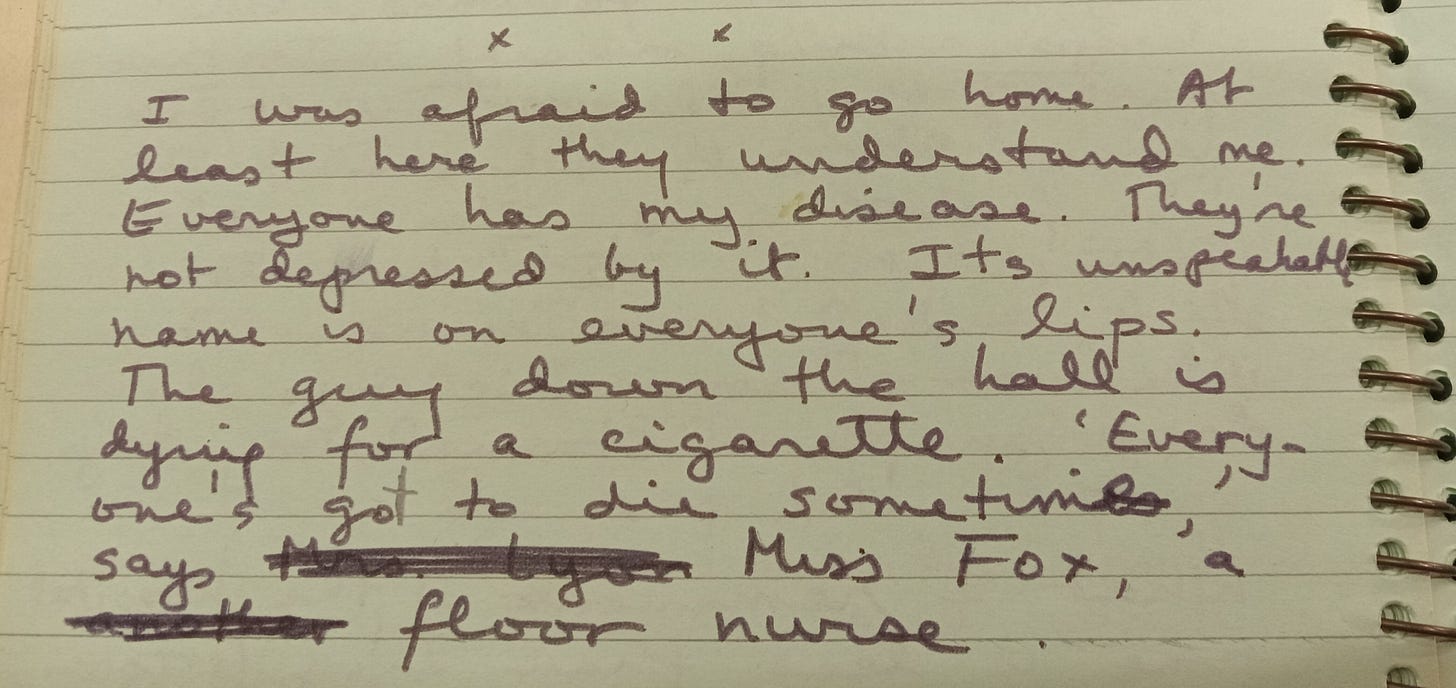

Sontag’s relentless attacks on herself don’t let up even during her cancer in the late 70s. The main reason she wrote a long essay about how we should stop making illness a moralized matter of blamable victims or brave survivors is that these terrible interpretations—like all such readings—were coming less from ‘society’ than from her own self-torturing that she had to accuse everyone else of in order to write her own way out of (with limited success).

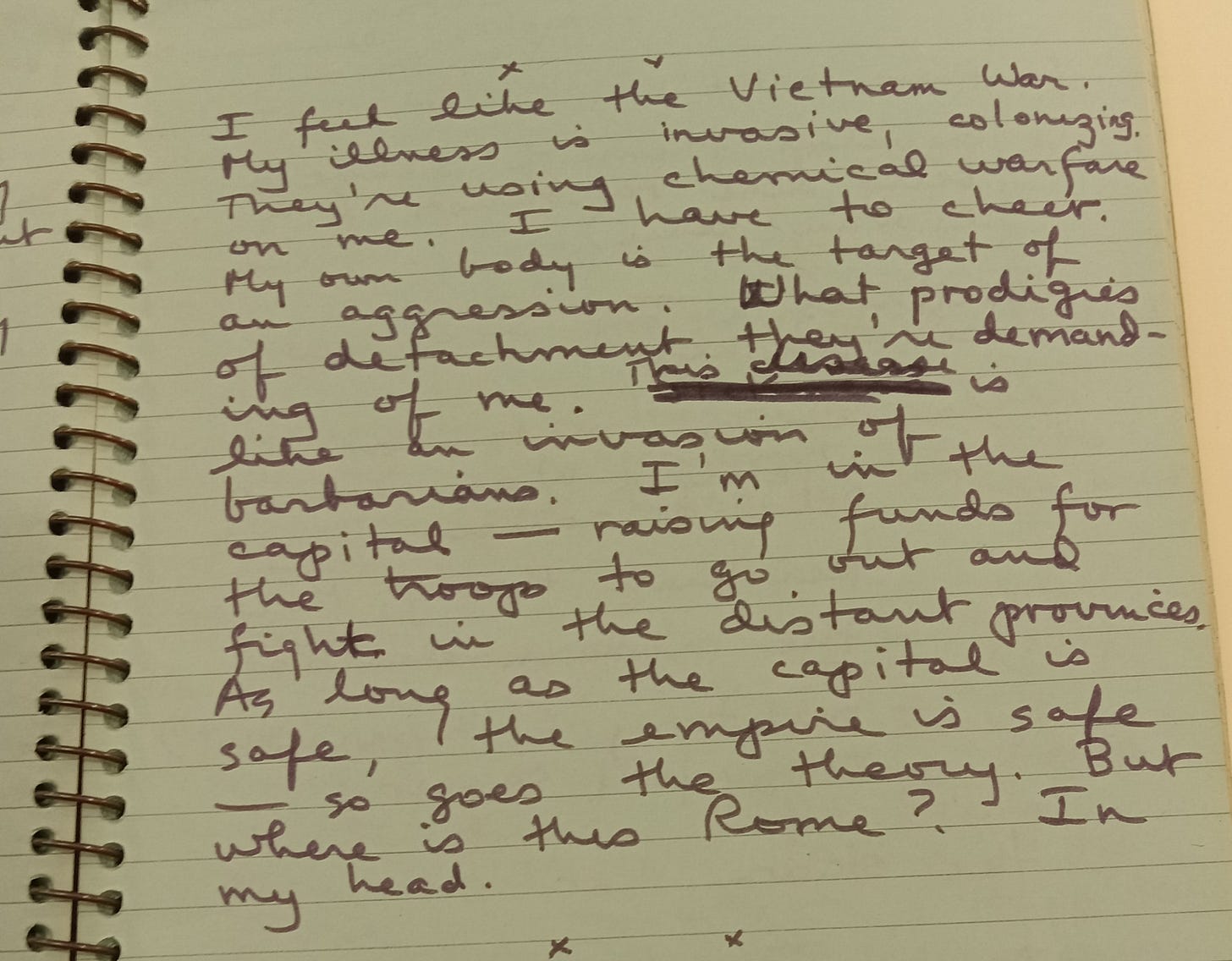

Cancer is Vietnam (during the Vietnam war Sontag infamously said white people were cancer, so I guess white people are also Vietnam):

Her struggle against making too much meaning out of illness—the refusal to see suffering as teaching us something, as “deep”—seems on the one hand very right, but then again also, awfully, to set her up to write what I’ve come to see (having once defended it) as a retarded essay about how we shouldn’t moralize and politicize and metaphorize AIDS, a disease that, after all, needed to be fought, to use a martial metaphor, and not merely set free (another metaphor!) from pernicious interpretation (when, after all, are we ever out of interpretation—or against it? we’re always up against one interpretation or another. You’d think a woman who styled herself a great follower of Nietzsche would be a little suspicious of campaigns against metaphor! [D.A. Miller btw has great polemical essay attacking Sontag’s AIDS essay—and one might also read him as contesting, in Bringing Out Barthes, her own closeting and self-closeted promotion of Barthes as an unpolitical enjoyer of texts; not that we’re anymore in the era when Sontag’s writings on Barthes set the terms for what Americans think about him]).

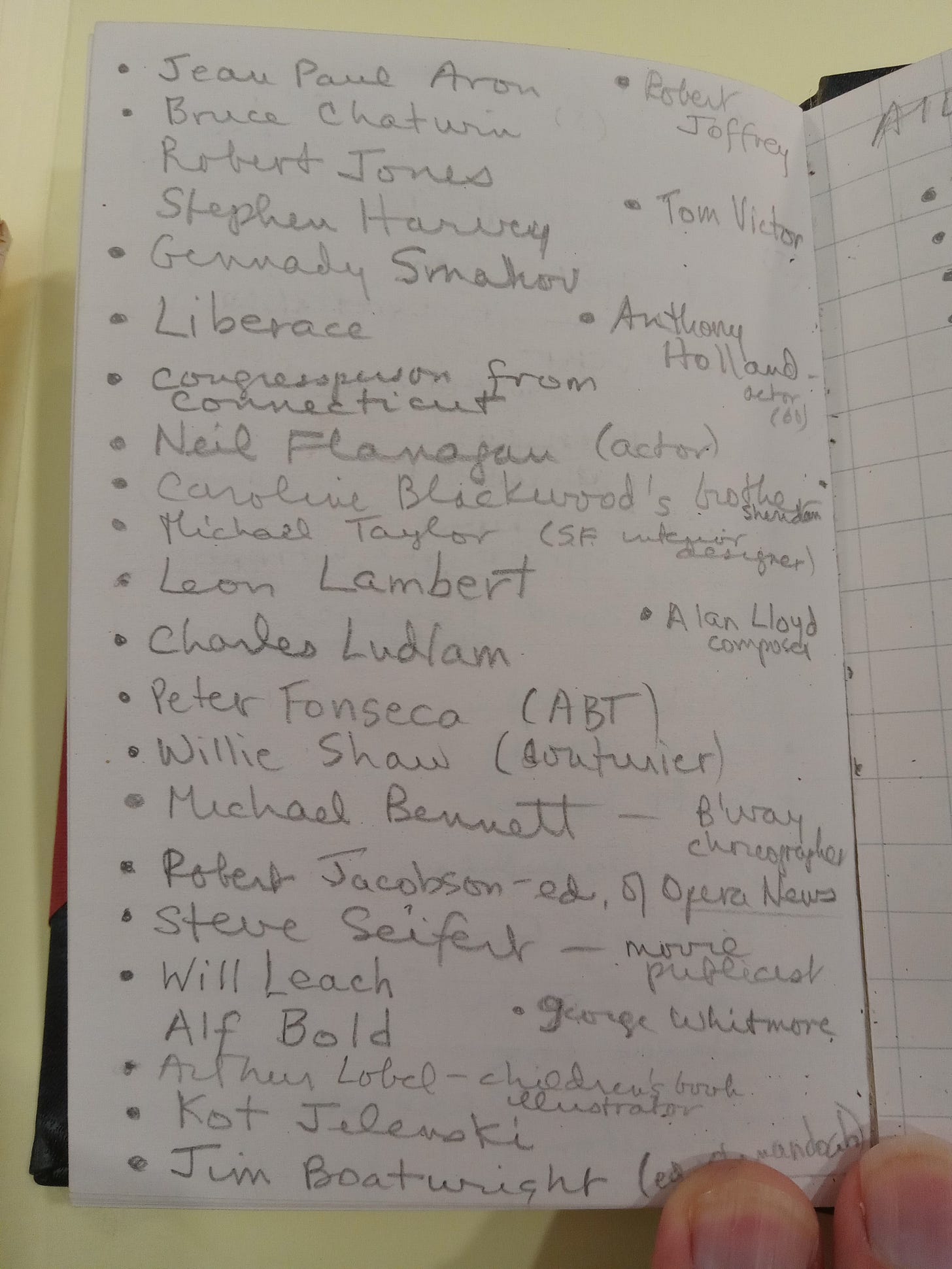

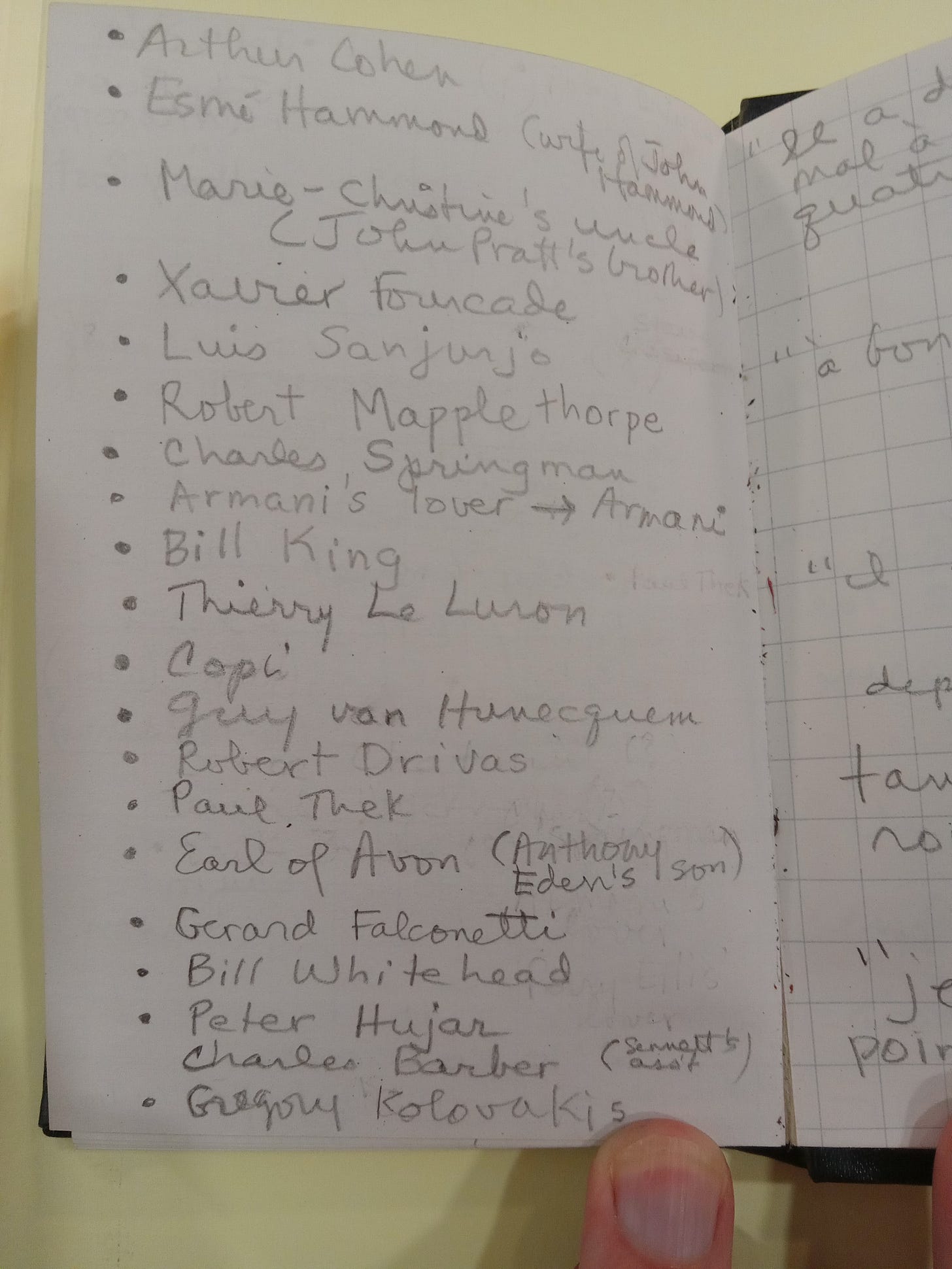

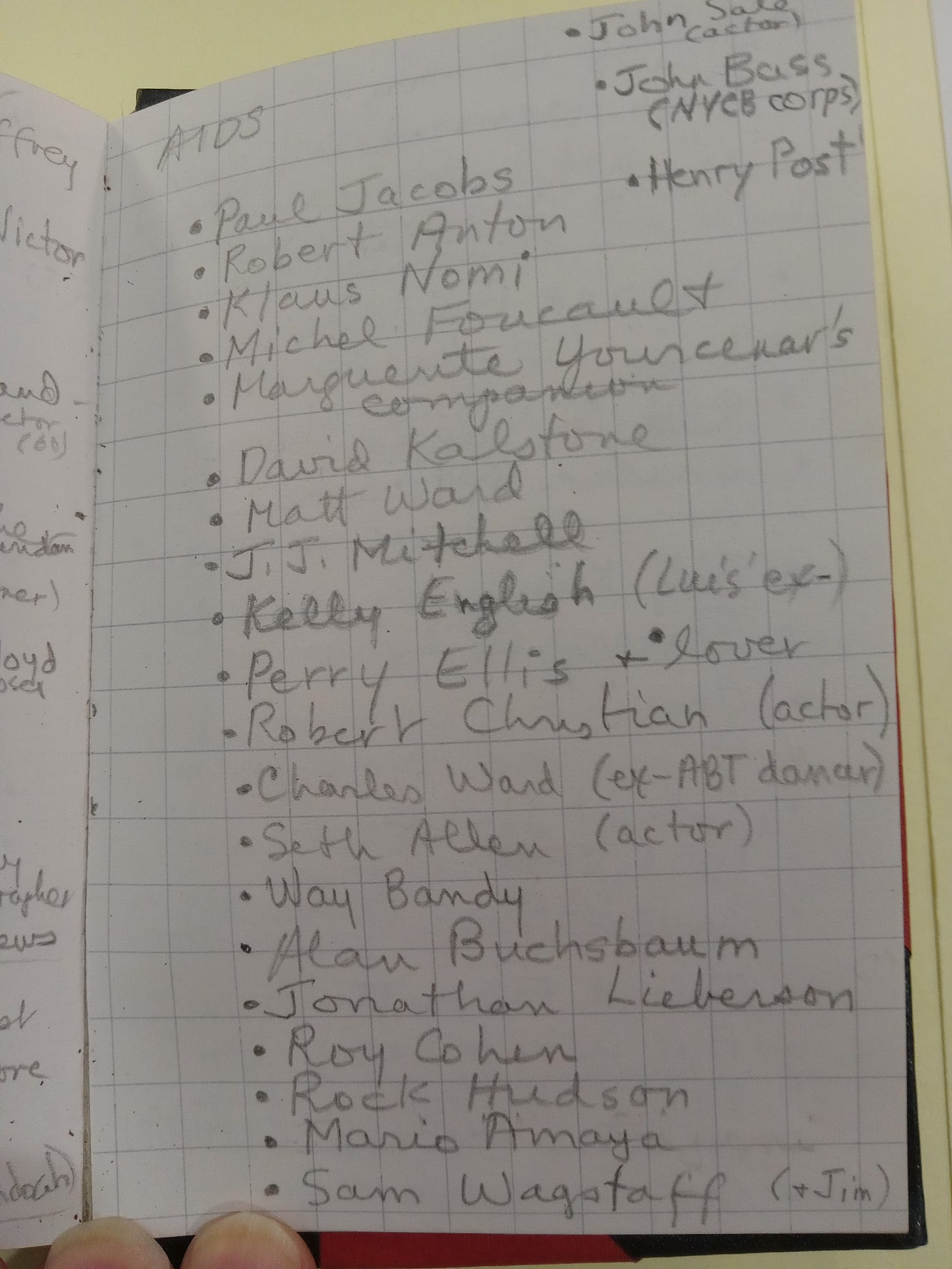

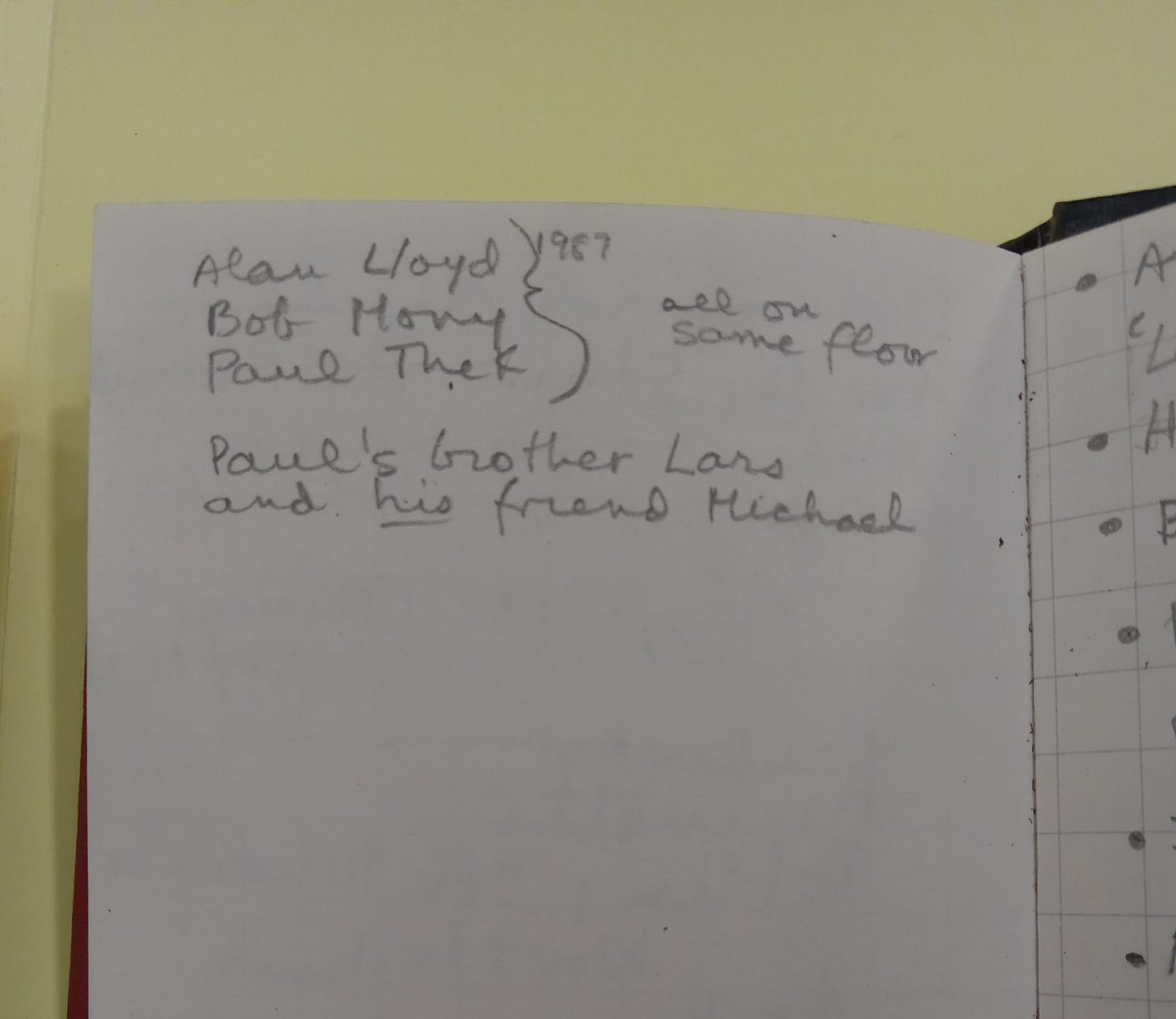

Sontag’s ice-cold AIDS essay and thin little fiction “The Way We Live Now” takes on a special poignancy of irrelevance read against the list she kept in 1987 of everyone she knew to have died from it, mixing up friends with acquaintances and celebrities:

Sontag had so much to say about Solidarity in Poland, about the dissidents in the Soviet Union, and later about Sarajevo, but what she wrote about AIDS—something happening where she lived, to people she knew, and not to foreigners whose situation she really knew nothing about except what her Soros handlers told her to keep the global liberal order afloat (Sontag had decided around the time she got cancer that the real cancer in the world wasn’t white people’s imperialist wars but all forms of unfreedom, or at least all forms of unfreedom that can be combatted through by signing petitions from Amnesty International and PEN), was disgustingly inadequate. I suppose I mustn’t say—it would be metaphorical!—that it makes me sick.

Her diaristic musings about male homosexuality in the years just before AIDS, 1976-81 don’t make me sick, but they are a combination of funny, stupid, and annoying.

Here’s one from her Tweet Drafts:

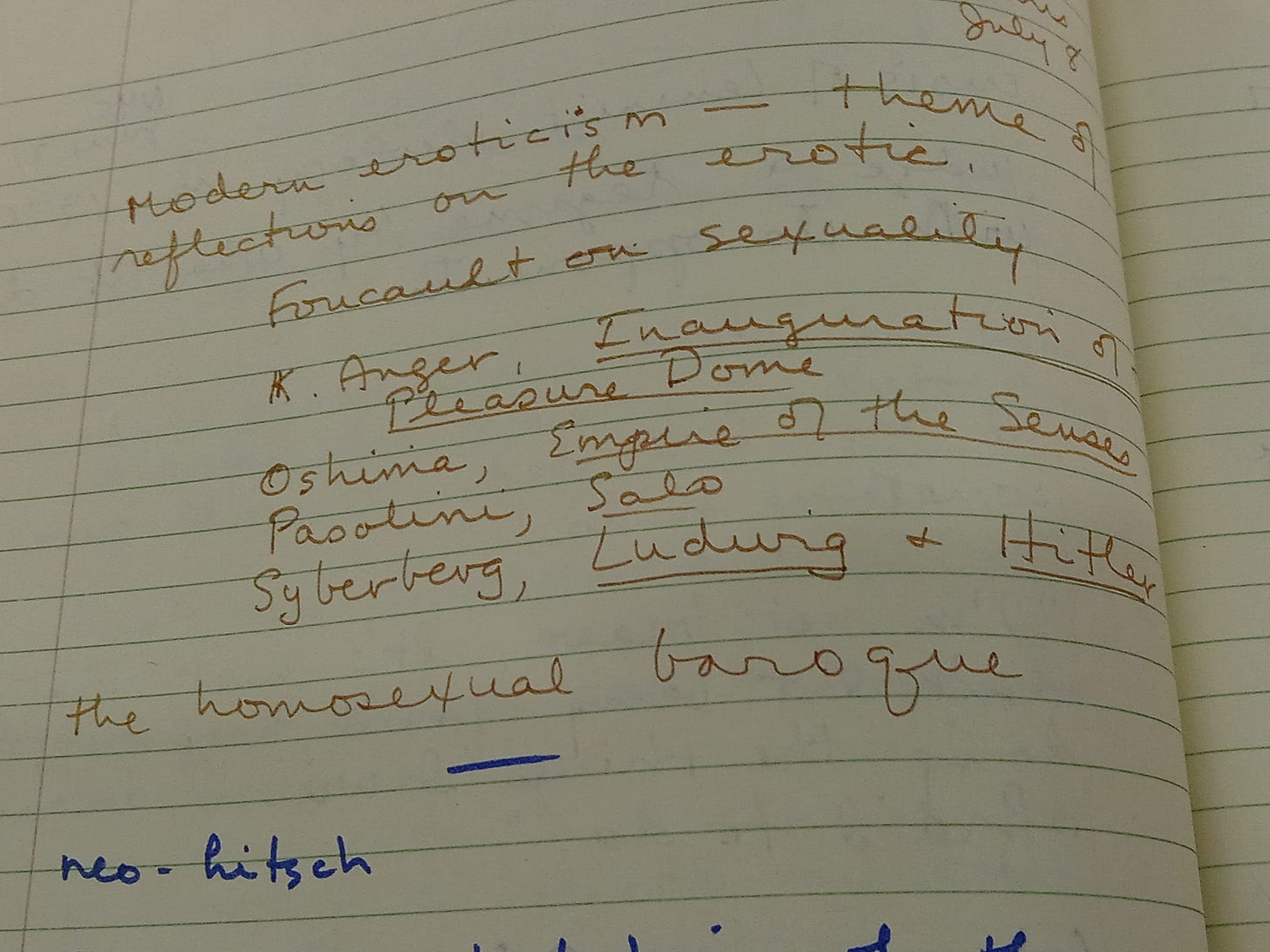

Elsewhere she has a thought about a genre to which, unlike camp, she didn’t devote an essay, but which will surely get one soon:

There is such a thing! If we take the homosexual baroque and neo-kitsch as involving some combination of flagrant/erotic transgressions with stagey, coded, half-serious formalism, we could add that there’s the (bad) 70s homosexual baroque of Ed White’s Noctures and Elena; the (fun) 70s homosexual baroque of Arthur Tress’ photography—going back to the interwar photography of George Platt Lynes and PaJaMa, forward to Dave Lachapelle, to Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Batman and Robin. Maybe! An essay for, say, the Importance of Being Jarrett Earnest…

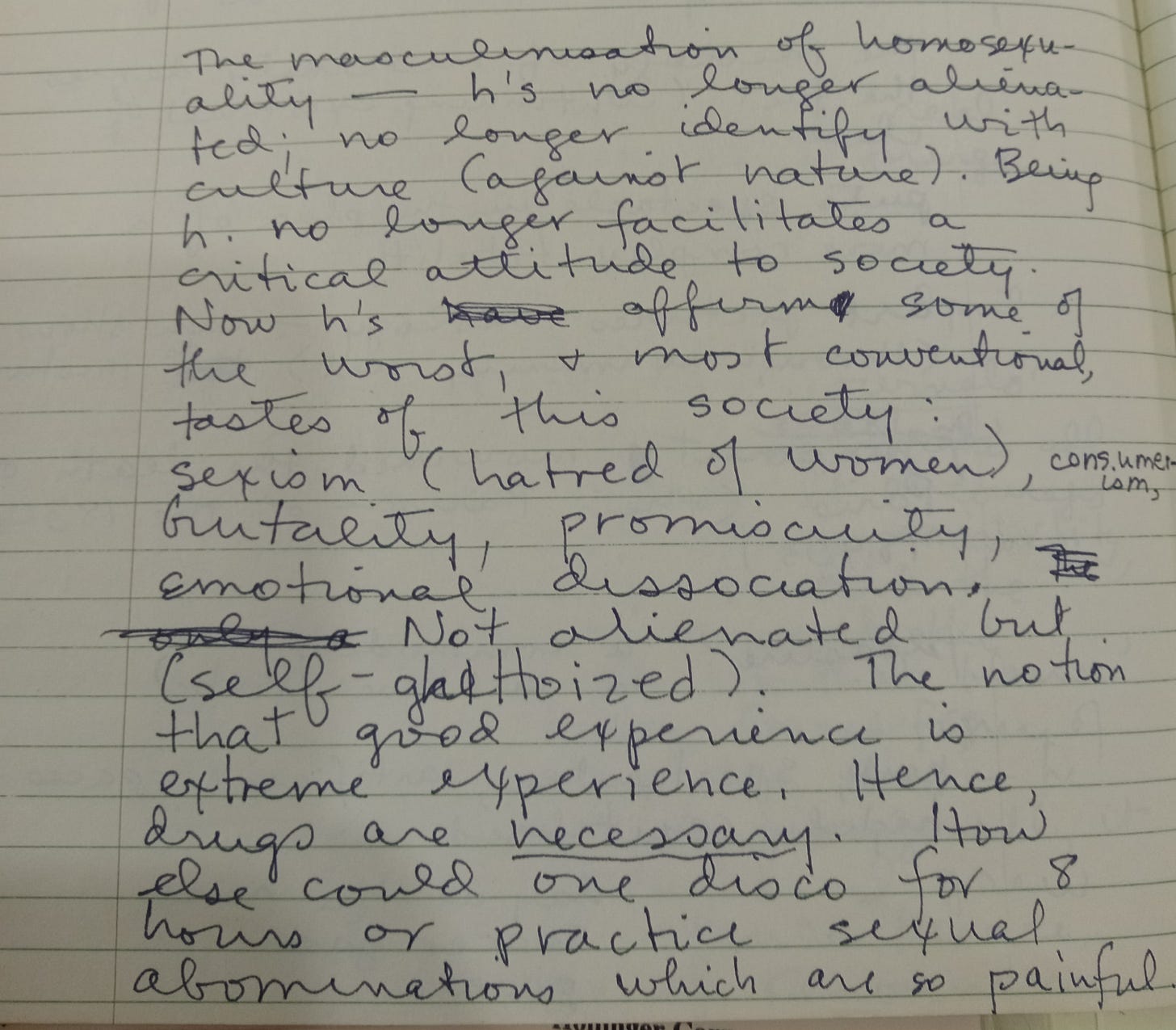

But Sontag was unhappy that gays were moving out of the old forms of indirection. Like Midge Dector (“The Boys on the Beach”) she complained gays in the late 70s were no longer fun swishes reading Ronald Firbank and collecting Tiffany lamps but drug-taking disco-dancing all-night-fisters who hardly lisped at all!

Male homosexuals ruined male homosexuality? Our supposed allies have been saying so since the beginning of time.

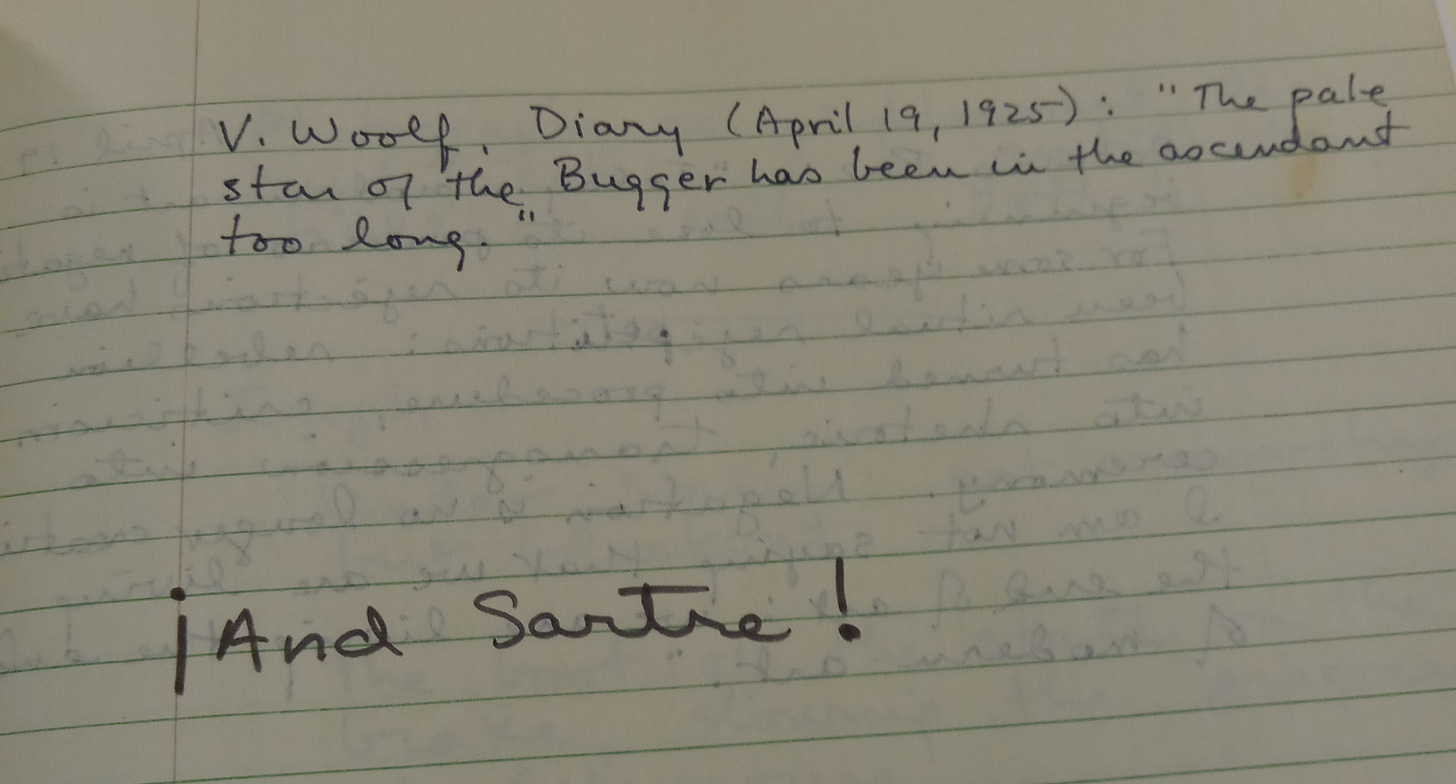

She seems to have enjoyed copying this quote from fellow seething mousy queer girl:

(the Sartre thing is her way of noting that he’d just died lol)

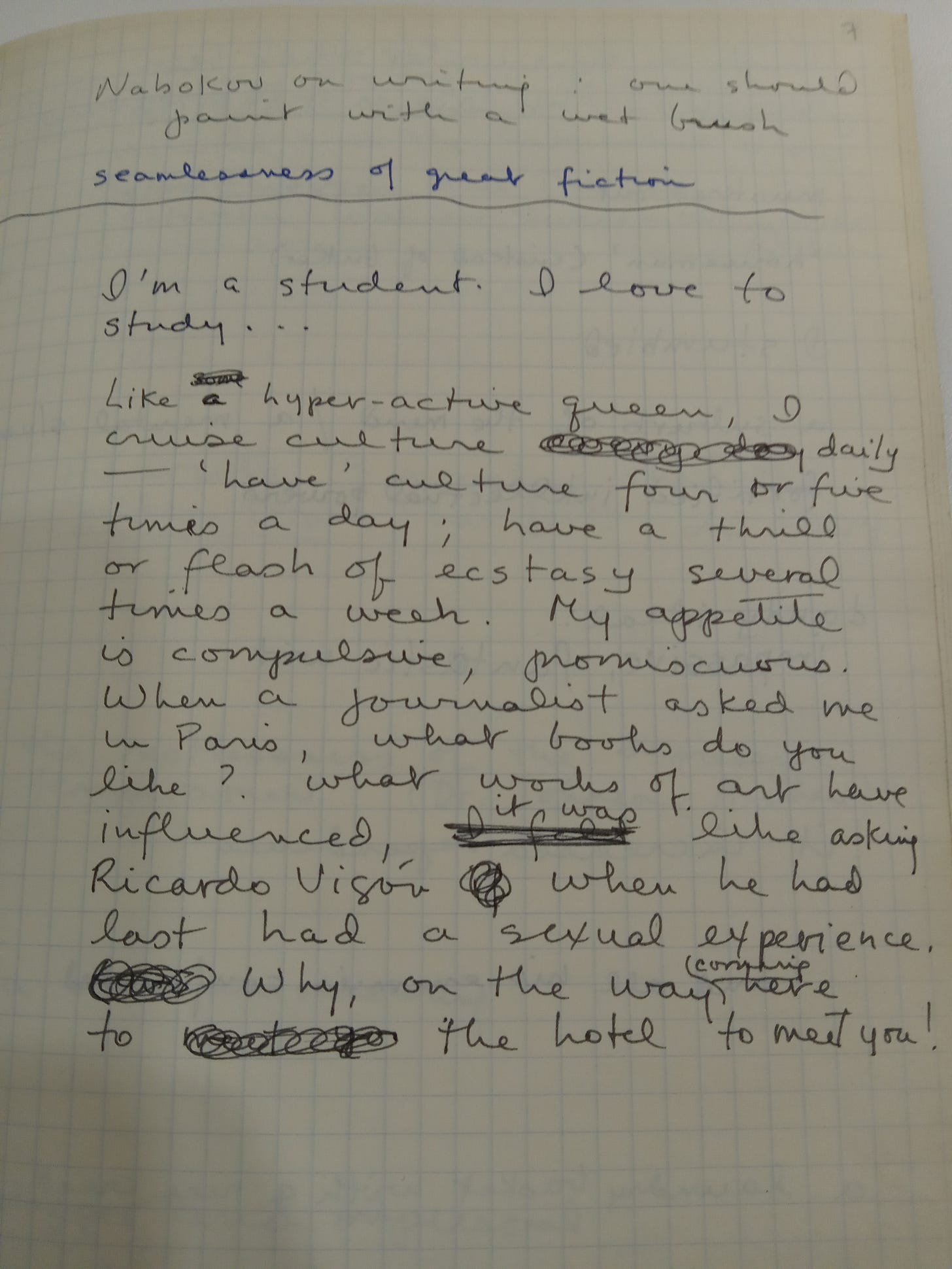

But of course—like gay men hating women—the resentment is caught up in a wish to be, half real, half (self)-mocking, lol I’m such a fag, I’m like gay for culture:

You can see why this material didn’t make it, directly, into her essays—and why a better son might have burned it. But since it’s there, for the reading, I can’t help but read it, after all, I’m a hyper-active culture-cruising queen…

I now know 3x more about Sontag.

Blake, I read this twice, but admittedly while eating/drinking alone. I think it starts strong, and somewhere loses momentum, goes off the rails. I don't think taking Chu so seriously helps. Anyway, I'm not going to try and think through this impression with any rigor, so take it fwiw. As always, keep up the good work.