There are many great figures of gay male woo-woo spirituality in late 20th century America, emblematic bearers of our national Emersonian-Whitmanian sublime tradition of bonkers woo. And some, happily enough, are couples, and, in fact, couples spiraling outward and upwards beyond the two into invisible communities of the plural and even past the limits of the human—James Merrill and David Jackson summoning shades of Ephraim and Auden and Stevens on the Ouija (Stevens admitted, from beyond the grave, that he’d tried it, I think twice, with guys), Michael Grumley and Robert Ferro searching for Atlantis and Bigfoot. Now, I myself am an Episcopalian and don’t really go in for ghosts or cryptids or crystals. But what am I doing on this Substack if not a kind of spirit-work, writing about dead people among whom, and along with you readers, I invoke a sort of spectral kinship?

Having written about Grumley on here before, I’m now going to look at his partner Ferro. Of the two, he was the better and more successful writer—an Iowa Program girl, along with Holleran (I recently read the wonderfully named Mark McGurl—you can’t make this stuff up—’s monograph The Program Era defending MFAs and their role in producing an American literature in which provincial whites and ethnic minorities can come learn to perform their diverse first-personal-but-therefore-representative experience in accessible, straightforward prose with a few characteristic slightly mannered but unobtrusive ‘poetic’ qualities, taking such examples as Raymond Carver and Sandra Cisneros. It’s an interesting take and certainly refreshing in the context of the seething about MFAs and Iowa specifically that goes on here on Substack and of which I myself have been a vector, in my rants about Garth Greenwell etc. But, if we’re thinking, say, how Iowa made contemporary American literature, particularly how it taught people to write and read a new [and ofc actually quite homogenized] multi-cultural canon then where are Andrew Holleran and Robert Ferro??? Where is the gay realist novel???, which after all came to be in part through their Iowa training—and concomitant desire to get published in The New Yorker—and which at some point, in the early 80s say, really established its hegemony when even Ed White broke out of the ‘baroque’ coded oblique fictions he’d been writing in the 70s [Nocturnes for the King of Naples, Forgetting Elena—which, btw, are terrible] to turn to fairly direct semi-autobiographical remembering-fiction. Which now we’ve all had far too much—the challenge would be to move beyond relying on one’s own experiences, to get back to imagination, fantasy, scale, range, without thereby giving up on the possibility of speaking to, about, for, within a particular community. It isn’t such a big ask; it’s only the premise of art.

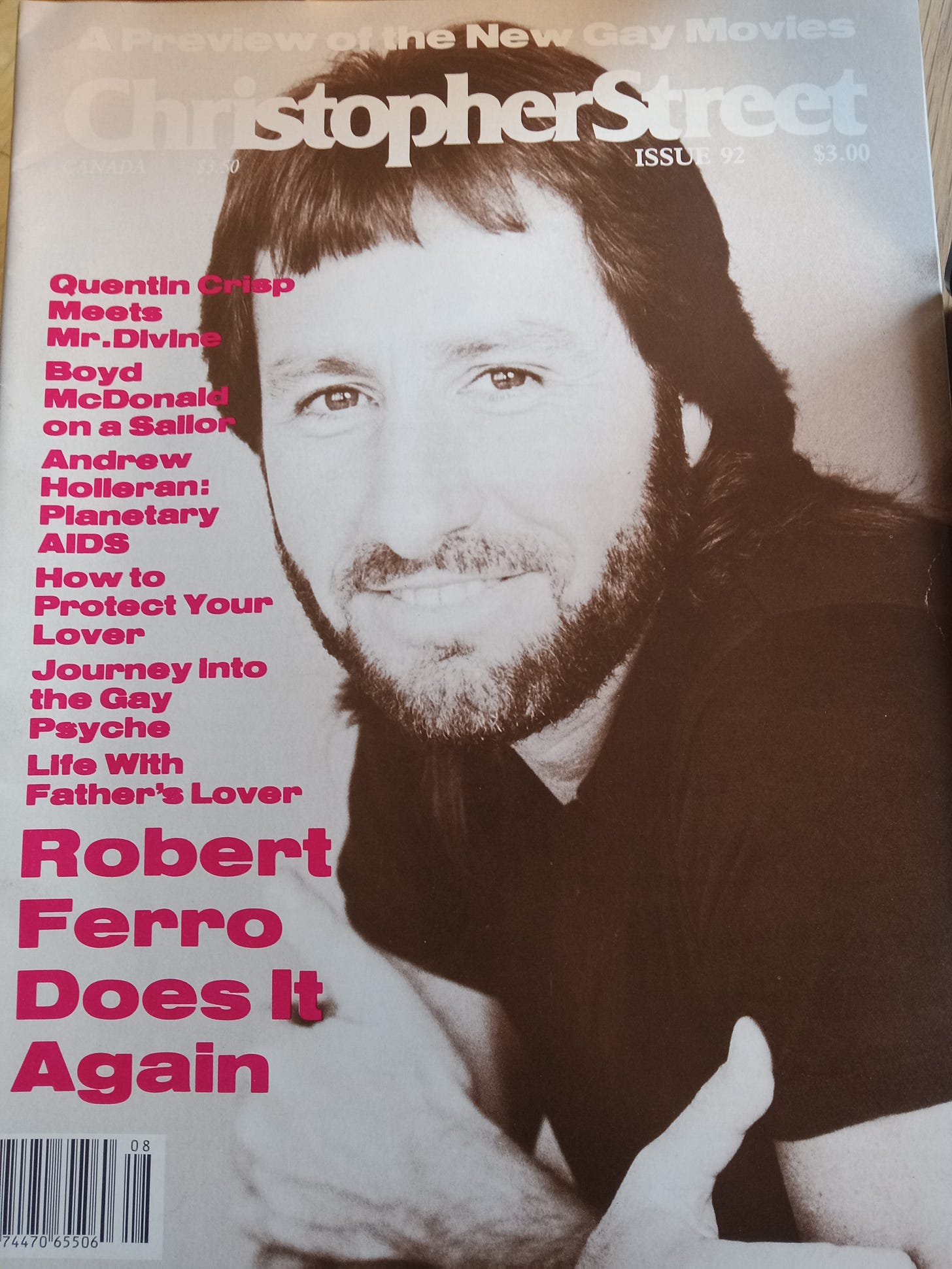

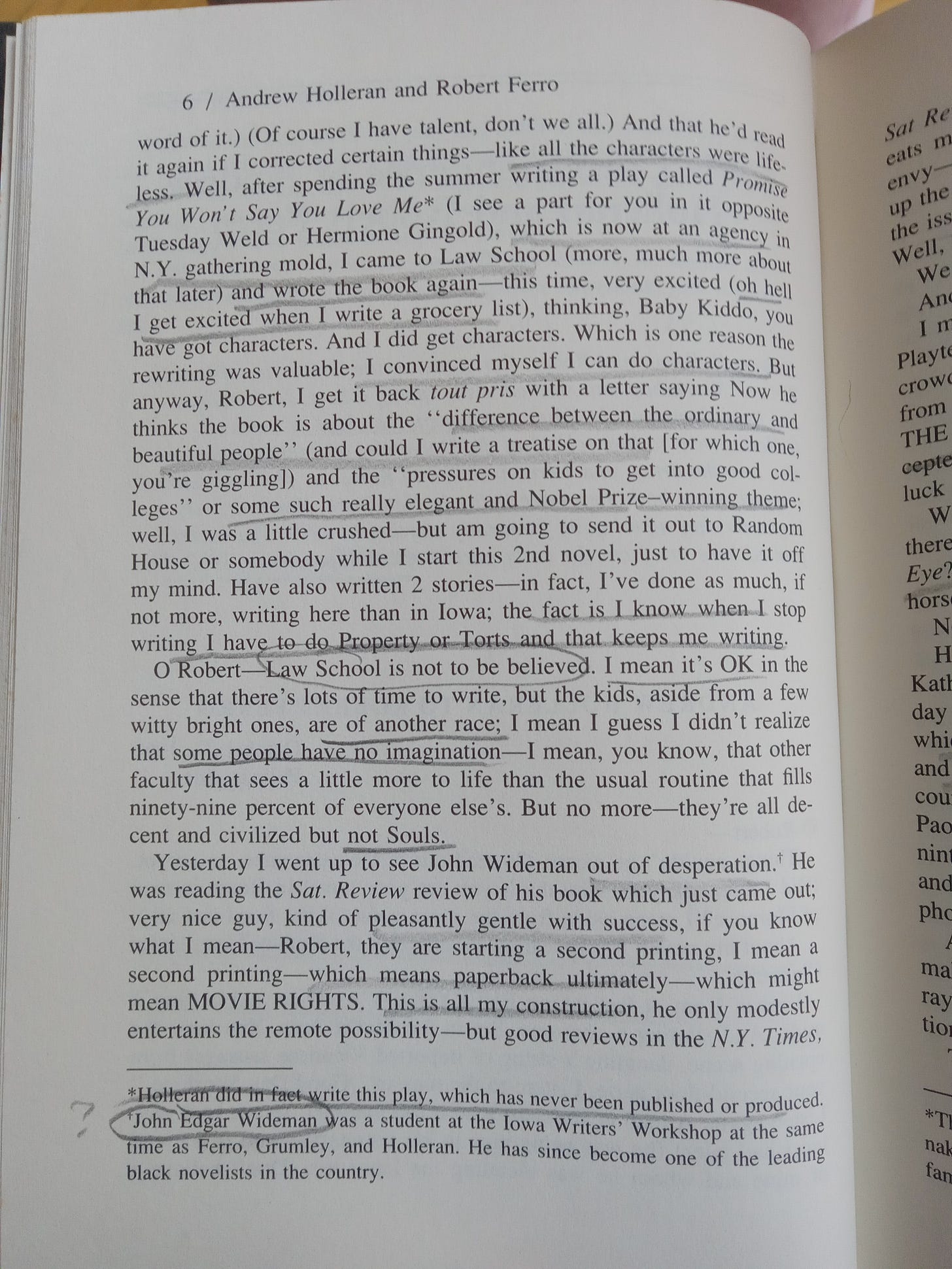

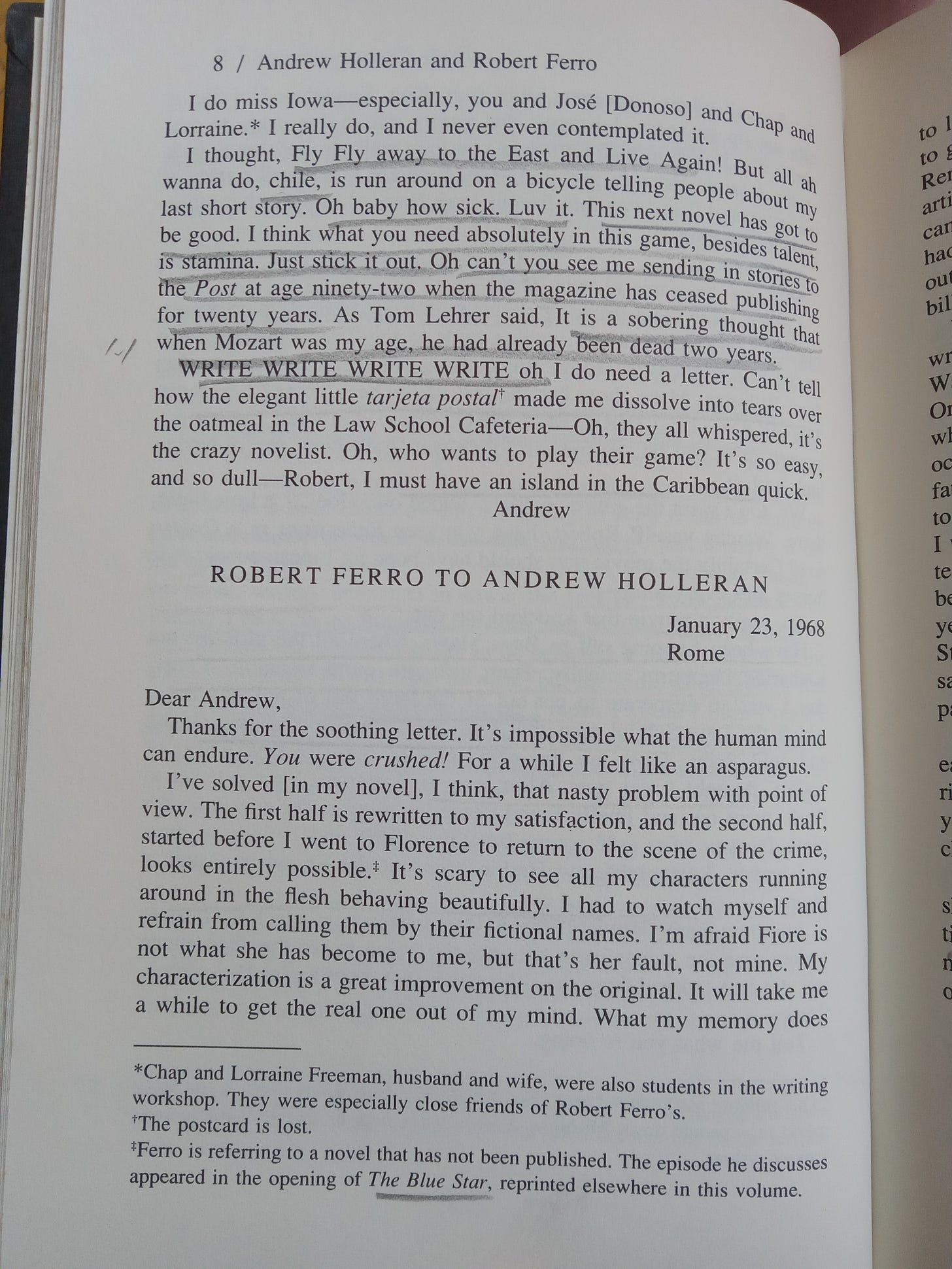

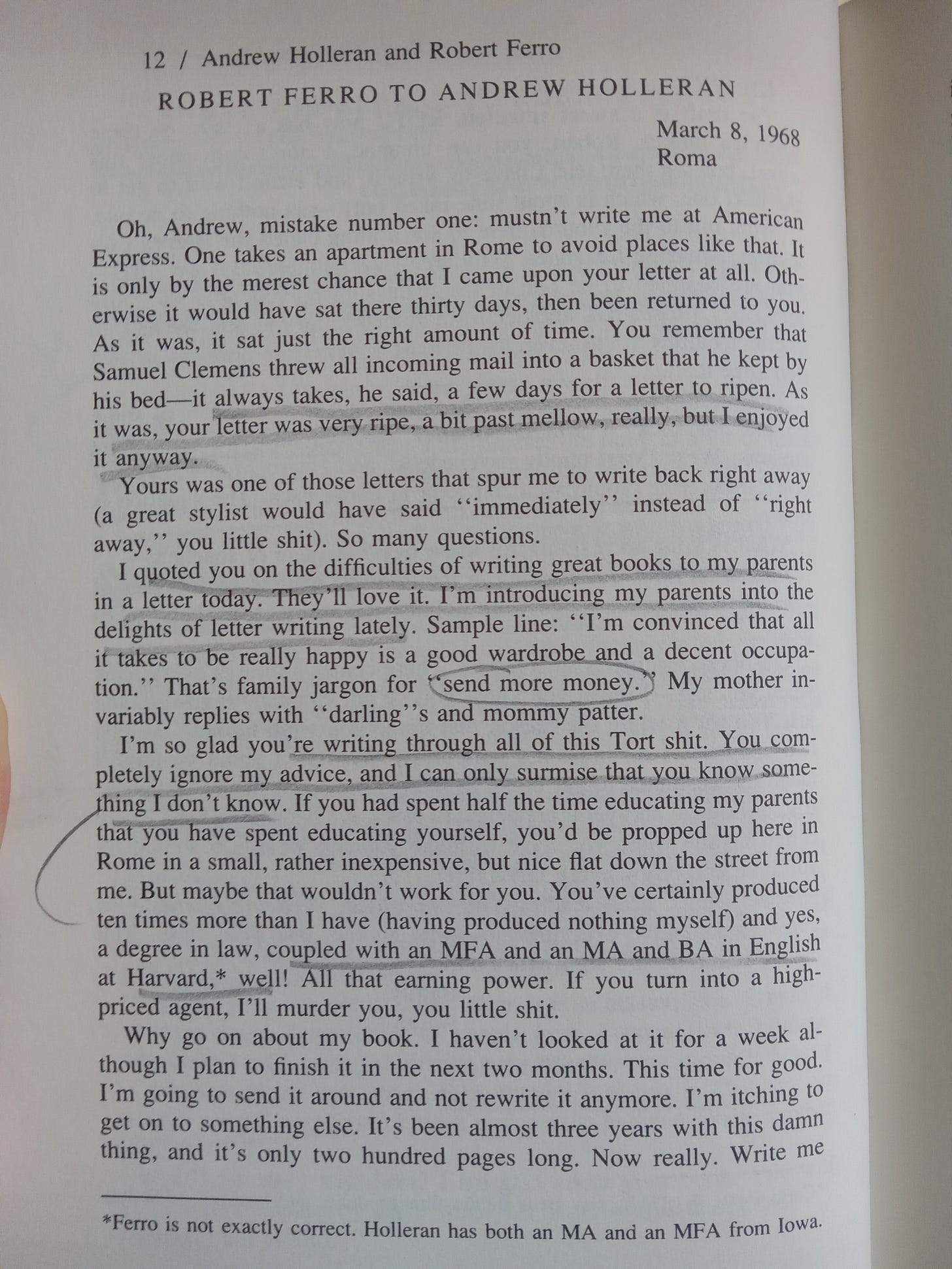

Ferro was the better writer of the Grumley-Ferro pair, as I said, but the other literary measure of his life was his friendship with Iowa-mate Holleran, to whom of course he doesn’t measure up. But, precisely because he was friends with Holleran—who appears, as we’ll see, in his final novel—he has a certain extra-aesthetic interest. Actually, maybe the best things either Holleran or Ferro wrote were their letters to each other, which started in the mid-20s after Iowa and continued until Ferro’s death from AIDS two decades later. The correspondence—excerpts of which were published by David Bergman in the 90s—astonishingly began while they were still not out to each other. Which is to say the following are, imagine, the two ostensibly straight men at the outset of their literary careers!

The girls are encouraging each other but also being subtly rivalrous—when Holleran published his early heterosexual (and boring) short story in The New Yorker, “The Holy Family,” Ferro seems to have been rather jealous (although Holleran spent the next several years getting nothing else in print). Ferro was the first to get a novel, well, novella, in print, 1977’s The Others.

It’s a sort of Ed White-type 1970s ‘baroque’ fiction—that is, it’s like someone imitating Sontag imitating the New Novel, already a generation out of date in France. A man boards a mysterious yacht that may be a product of his own imagination, inhabited by characters who begin to suspect their own unreality. To pass the time, they tell each other curious fable-like stories. What this all adds up to isn’t clear, but there is a fun? atmosphere of harmless wistful spooky oddness.

A lot of features of this story will appear in Ferro’s three subsequent gay novels—travel in Italy (where Ferro lived after Iowa—there is a whole cycle of gaylit, with him, Ed White, and then David Leavitt, thinking that living in Italy for a while is something interesting for other people to hear about. It’s not! I don’t want to see pics from your study abroad trip), vague affluence/indolence, problems of the spirit. No one I’m sure would read it on its own merits today, but it’s worth looking at if only to see what the people who would become the gay writers were having to write themselves out of—and what tics and habits they didn’t.

Ferro’s first gay novel, The Family of Max Desir (1983) sounds from the title like, and in some ways is, a domestic bourgeois novel about coming to terms with your family. In this case, a couple of deaths go along with the gay protagonist incorporating his partner into his Italian-American family. It’s pretty snoozy, except that it starts wildly and has some crazy asides—a voodoo-worshipping neighbor whom the partner sometimes sleeps with, messages from space, and a recurring fantasy about going up the Amazon Aguirre-style:

The visions don’t help the novel work as a novel—they get in the way and don’t add up to anything that make sense—I wish there were more of them although maybe this isn’t a problem to be solved with volume. But I do like them! The sense of gay domesticity being enriched and undermined at once not only by infidelities (like Merrill and Jackson, Ferro and Grumley seem to have both been bottoms who didn’t fuck each other anymore and had a system for sleeping around with ‘exotic’ types unlike themselves—for Merrill, Greek trade; for F&G, black guys) but, like every routine, by desires weirder than the sexual, fantasies of an faraway and even extra-planetary outside. Philip K Dick getting shot with the Jesus Laser but make him an Iowa girlie.

Ferro’s follow-up, The Blue Star (1985), is sort of a combination of The Others and Max Desir—set among idle American expats in Italy lazily rehearsing a vague romantic plot. To invoke a not specifically gay tradition, it’s like a shapeless Jamesian or Forsterian Americans-abroad novel, or a rather dull version of Call Me By Your Name or the superior (because truly insane) Max Brodkey novel about an American boy buttfucking his buddy in Italy, Profane Friendship (1994)—I promise to write about Brodkey another time.

What is interesting about The Blue Star, sort of, a side-plot in which a character is a scion of an ancient Masonic lineage that also for obscure reasons designed Central Park and buried treasure there. This National Treasure thing never become a thriller, anymore than the main plot becomes a romance, but it is somewhat more elaborated than the fantasies of Max Desir. I’ll skip giving any excerpts, though, because unfortunately the prose just isn’t worth the reading.

As he was himself dying of it, Ferro wrote an AIDS novel, Second Son (1988). AIDS didn’t make anyone a better writer—except maybe Paul Monette in Love Alone (which again I’ll write about later)—how could it have possibly made anyone anything but a worse writer, or a non-writer? And I understand why people wouldn’t want to write about it, or read about it—I still clench thinking about it, have to psych myself up for it, tell myself that it’s important (the category of The Important being one I usually despise and avoid) and that if I don’t get down to writing about a book about it (well, one, I’ll be 40 in a few years and still won’t have a book—how embarrassing) then it’ll be Sarah Schulman and Ben Miller writing our history.

Second Son isn’t a great novel, as a novel—it’s naturally enough shapeless since all of his previous novels were, and since he was dying as he wrote it. The novel is about him and Michael Grumley dying, more or less, only in this version the Ferro protagonist isn’t a writer. What makes it bearable reading is the presence via letter of Holleran, who appears as Matthew Black, and is himself at work on the novel that becomes The Beauty of Men, Holleran’s third and in some ways best, saddest novel (it’s a cross between Barthes’ Fragments of a Lover’s Discourse and Mourning Diary—a meditation on a doomed unreciprocated passion and the death of his mother—I’m in no hurry to ever re-read it, but I don’t think any book has made me cry so much).

This is, you will remember, exactly the style of the letters Ferro exchanged with Holleran and Holleran exchanged with Stambolian. Ferro turns them into something more than slice-of-life though by assigning to the Holleran character his own interest in the occult—Holleran gets, like Merrill at the Ouija, at first skeptically-mockingly curious and then matter-of-fact about the idea of escaping Earth:

The Ferro character and friends debate whether Holleran’s planet is some kind of metaphor for suicide, for his novel, or who knows what. Meanwhile he keeps getting more Sirius.

Is Ferro parodying his own earlier obsessions with occult phenomena—the book on Atlantis he and Grumley wrote together as young men—or with his dying generation’s hopes for a miracle that would cure them, whether AZT or macrobiotic diet or Mexican gemstones (one of the saddest afternoons I spent looking at gay historical material in the last year was working through a box of ‘alternative medicine’ zines from the 80s and early 90s that tried to keep AIDS victims upbeat about the possibility of healing through goddess-worship and I-Ching-ing—that amid so much collective death people still, of course, had to go on making up reasons to hope and to feel in control of their own health, as if you could visualize your way out of Auschwitz, is just unbearable to consider)—or religion? I myself think praying to God (which I do) must sound like this to anyone in their right mind, or even to God himself if he hears. It is so stupid and pitiful and necessary to hope.

Ferro’s-Holleran’s fantasy also sounds a lot like the private queer religion Merrill had started inventing in the 70s—the Ouija board revealed that gay people are a superior spiritual race, and taught him various complicated and boring lessons about our need to rein in science, industry etc to foster a new relation to the Earth and the magical immortal beings we actually are. Any elaborated version of our wishes not to die and not to be alone sounds so heartbreakingly dumb, except that sometimes we can be distracted from how dumb it is by either the routine prestige that religion (lots of other people believing this shit) or aesthetics (lots of people admiring how singularly one person has expressed the wishes as if he did not really need them to be fulfilled, as if they were only a kind of joke) lend them, making us take them seriously rather than laugh or cry. Not that literature or religion, of course, actually work.

This is the novel’s last paragraph:

The fantasy—as literature, as religion, as delusion, whatever it is—if it doesn’t save us, at least holds us together as we wait for the end—and as we wait gives us too a voice in which to write to, about, and in the voice of our absent friends, so they can keep us company before we go.

What I’m saying, I think, is not the sort of recuperation Langdon Hammer wants to make in his enormous Merrill biography of The Changing Light at Sandover as something like ‘our Paradise Lost’ (Milton in a post-heroic, home-y, homo-y, twee key—proving Eliot wrong [as Hammer was also out to do in Janus-Faced Modernism via his defense of Crane], showing that a right kind of epic, intimate, idiosyncratic, queerly liberal, is still possible for us post-moderns. That’s not the case I’d want to make for Ferro—whom anyway I don’t need to defend as a canonizable genius the way Merrill ought to be defended. But in a way as a lesser artist he better shows how much this era of gay writing, which saw the emergence and possible annihilation of a ‘gay world’ and would naturally wish that somewhere there would be another gay world to escape to, was a work of imagining (with) friends.

Blake is a fantastic critic and stylist, and a very good mind. One of the more intriguing projects I'm engaging on Substack.