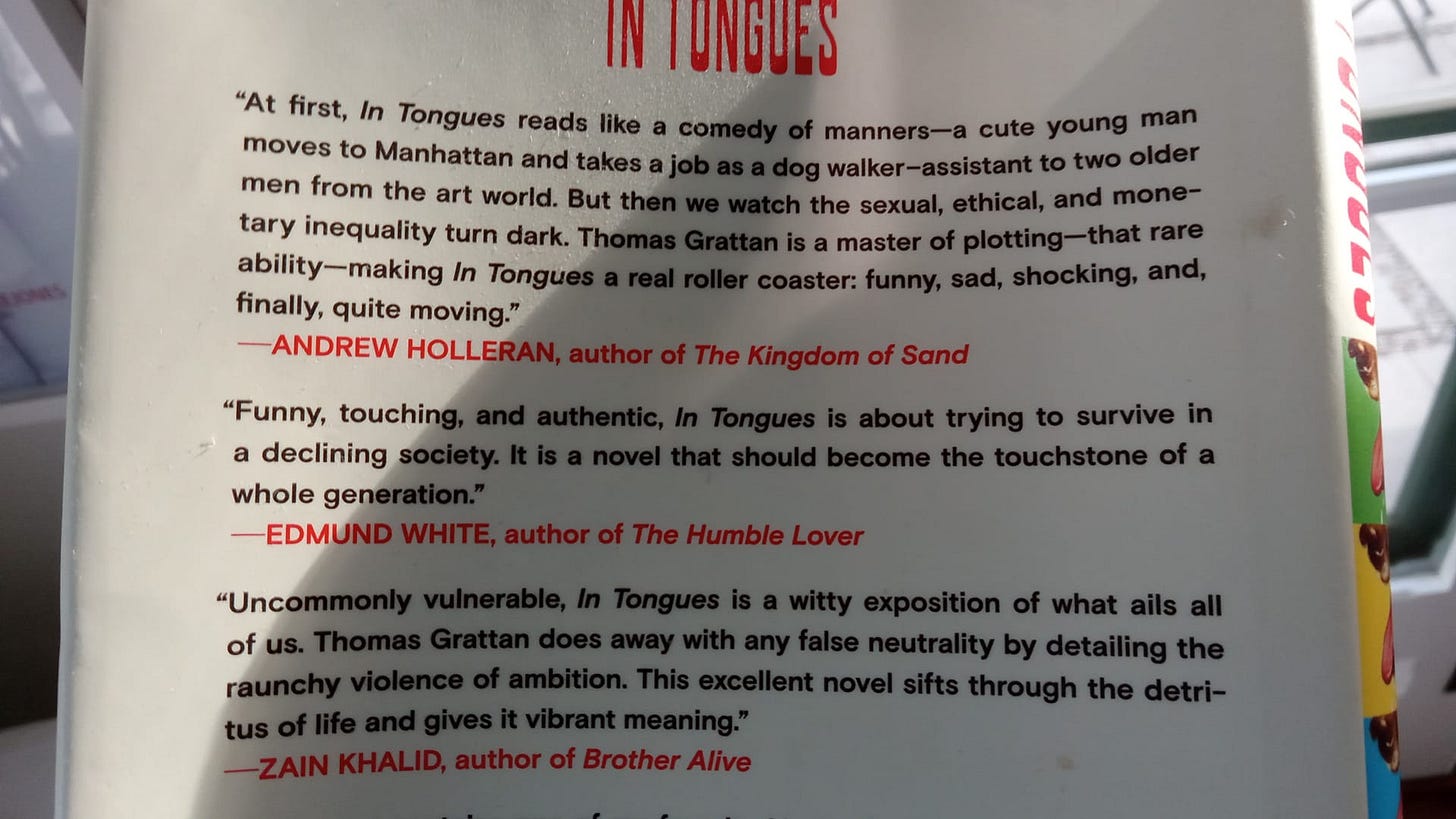

I’d said, hadn’t I, that this would be a year for not writing about things I don’t like, so having spent the afternoon with Thomas Grattan’s acclaimed new gay novel In Tongues, I’ll just note the contrast between these blurbs (“The touchstone of a whole generation!”):

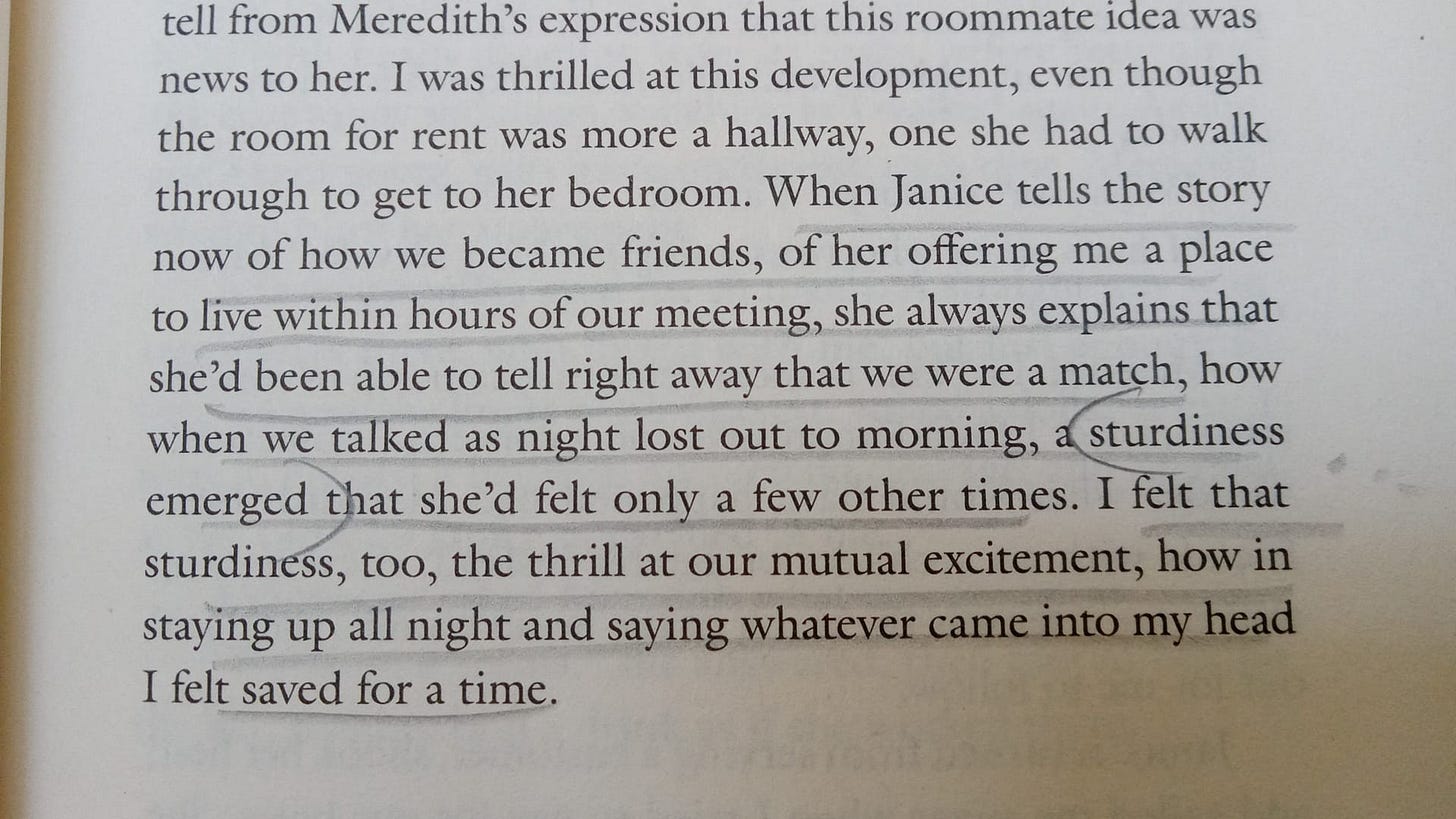

—with these two passages, typical and not by any means the worst, of affectedly flat prose with a few gratingly poetic touches which combine to make for ‘literature’:

Snore… This is giving me nothing, except the sucky flourishes of “sturdiness emerged” and “riot of bodies.”

Blurbs and the blurbing liars who blurb them!

As for the social commentary and plot that Holleran and White—the liars in question—praise, the novel is the story of a poor gay dog-walker who gets into a sort of shapeless professional-sexual situationship with a rich older couple of New York art world queens in a story that answers the question ‘What if The White Lotus were a mirthless slog?’ (Btw that Mike White also wrote The Emoji Movie script is for me ‘our’ version of Faulkner writing movies about sexy fighter pilots).

But all that negativity, that’s the old me talking. The hater. The new me is an enjoyer. She’s thinking about queer interwar modernism and not even minding that it’s also terrible (the secret about literature—gay or otherwise—is that it’s almost all terrible and that, but now I’m talking to myself here, one has to somehow keep this fact in mind without succumbing either to complete pessimism or to delusional cheerfulness that says ‘what do you mean there’s lots of great stuff! Just look at… [and here my interlocutor inevitably names a pile of absolute trash]).

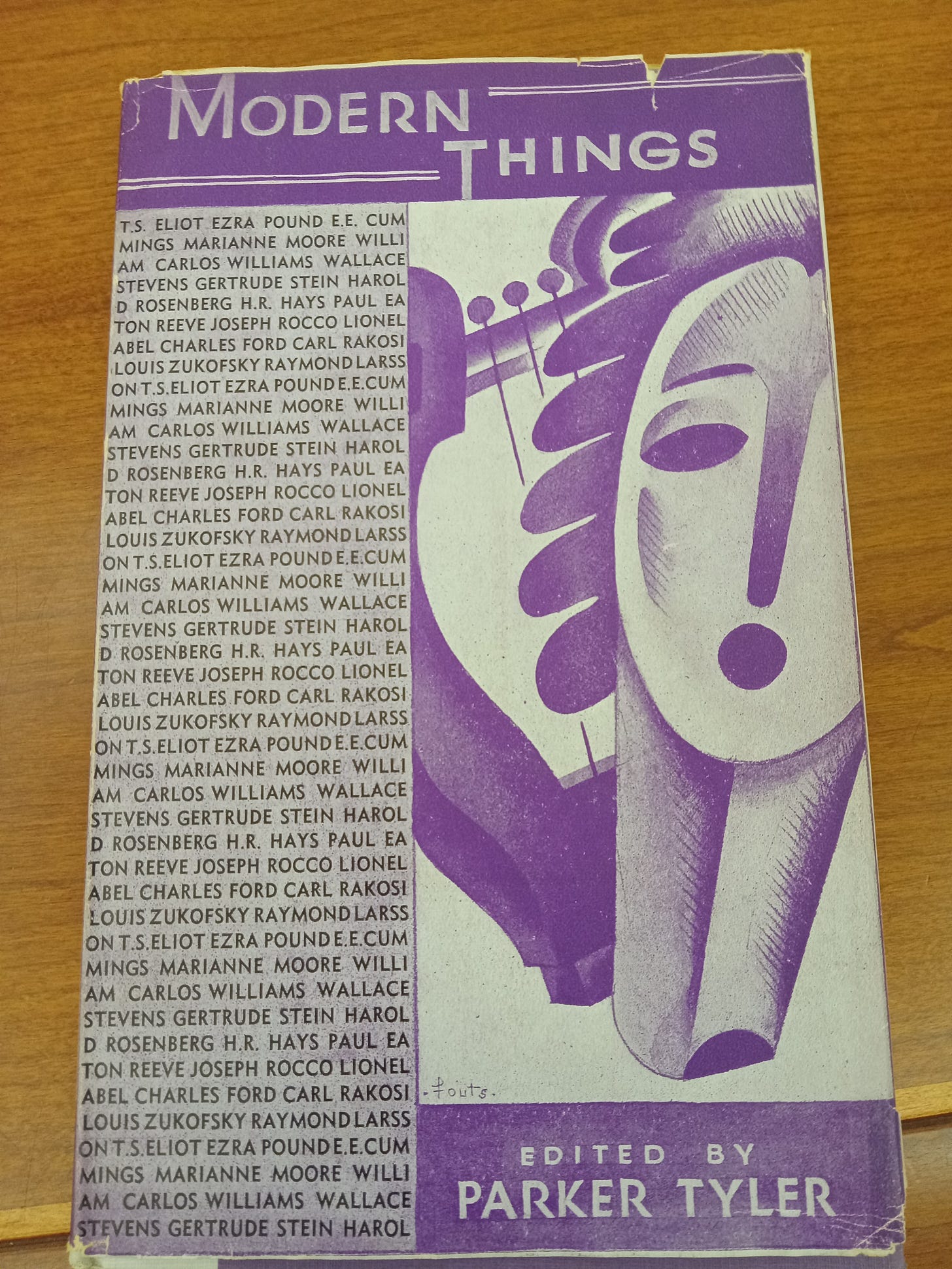

I already posted about Charles Henri Ford and his collaborator Parker Tyler, whom I’m interested in not least because these two southern homos were in the 1930s and 40s friends, mentors and benefactors of the then-poet, later-artcritic Harold Rosenberg, who would go on in the 1960s and 70s to be, along with his friend Hannah Arendt, the teacher of Michael Denneny, future leading gay publisher, in the University of Chicago’s Social Thought program.

I’ve been convincing myself and hope to spend the next few years convincing if not literally you then a number of people, reader, like you that this little family of American letters is ‘our’ (whoever we are) Frankfurt School, New York Intellectuals, etc.—that there’s a scene, a filiation, a heritage for the having here. That there’s something at work in America stretching from Blues and View to Christopher Street and Men on Men running through Thinking Without a Bannister and The Tradition of the New, linking modernism’s search for aesthetic forms of freedom to mid-century free-thinkers who weren’t liberals but also weren’t not to late twentieth-century gay identity rightly understood and legitimated against the whiny critiques of left and right.

Not that what came out of this tradition I’ve imagined was all or even mostly good! But I assert the same vibeological rights over mere historical fact and obvious aesthetic deficits that Earnest-Zwirner assumed in putting together that ‘The Young and the Evil’ show, or that whatsherface did in naming ‘Nineth Street Women,’ to declare myself that Some Gays and a Few Straights I Like are icons, legends, and (forever) the moment.

With nothing further to declare…

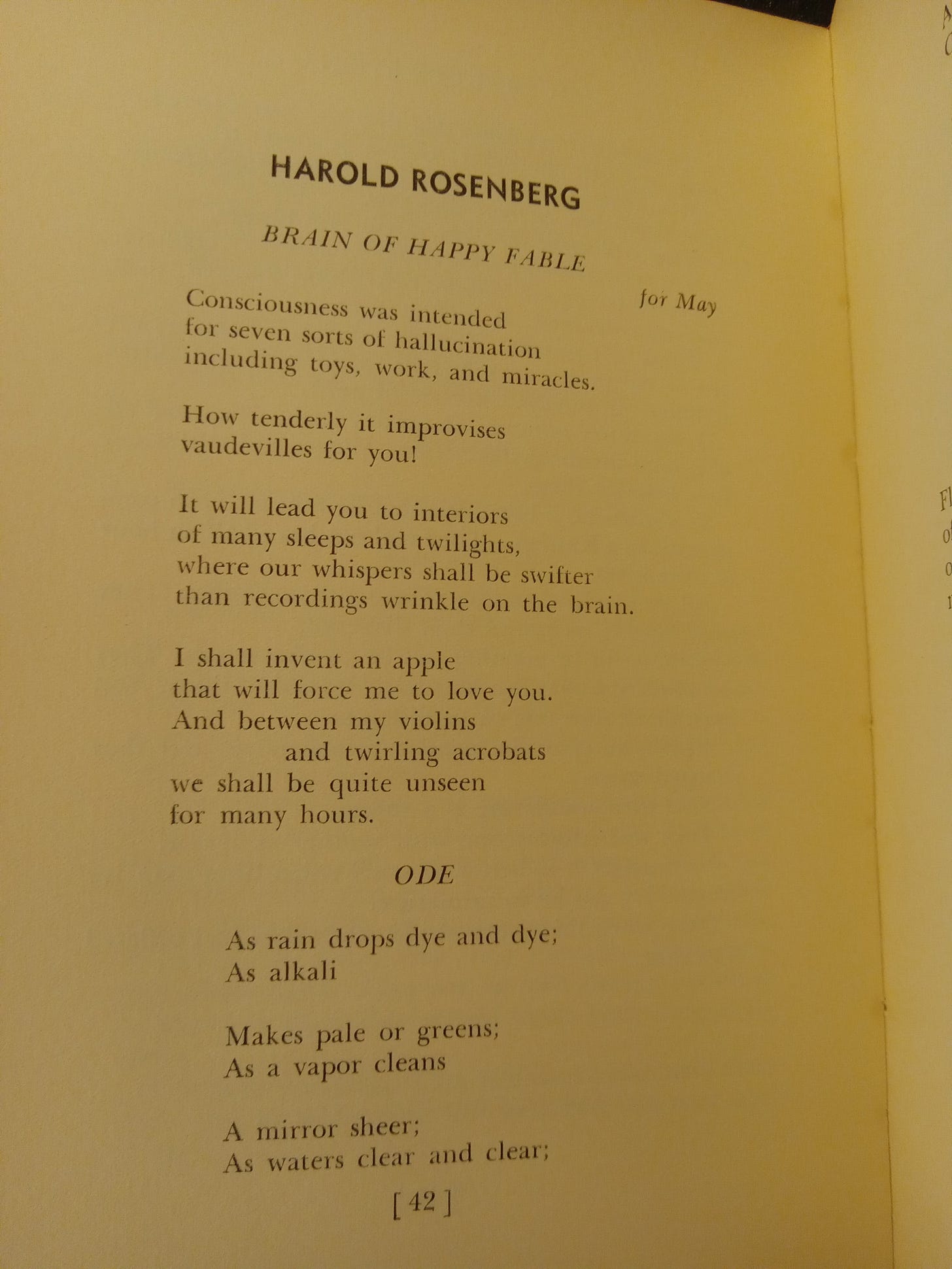

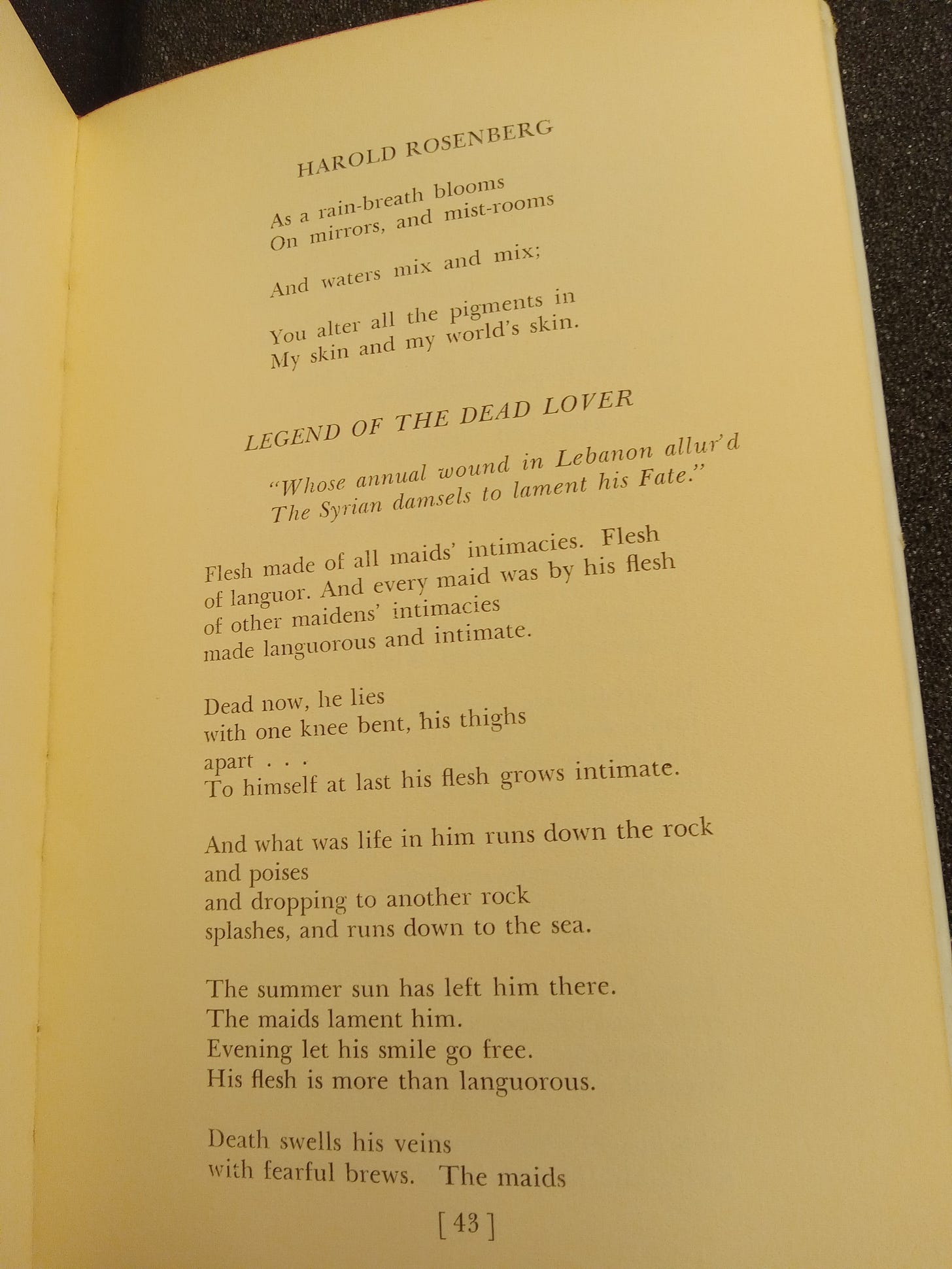

I’ve already made fun of Tyler and Ford’s bad poetry, and noted that they were also poetry editors in their magazines. In addition to which Tyler put together this at-the-time influential anthology of modernism in 1934. There are lots of names you’ll recognize, names that would appear in any discussion of modern poetry today—but also lots of odd ones, like the now obscure Catholic poet Raymond Larsson (I once got a grant to spend some days looking at Larsson’s papers in Notre Dame, hoping that behind the few poems he’d published in interwar modernist periodicals like transition there would be among his many boxes of unpublished material—much of it written after his conversion and subsequent mental breakdown [Jesus won’t necessarily cure you girls—a man can’t fix crazy]—good or at least interesting stuff, but there wasn’t. I spent some sad hours flipping through the documentation of a wasted life)—and Harold Rosenberg, who I think has more pages in this book than anyone else. As I said of Auden in the post-war years, you’ve got to know who to blow to get ahead in poetry…

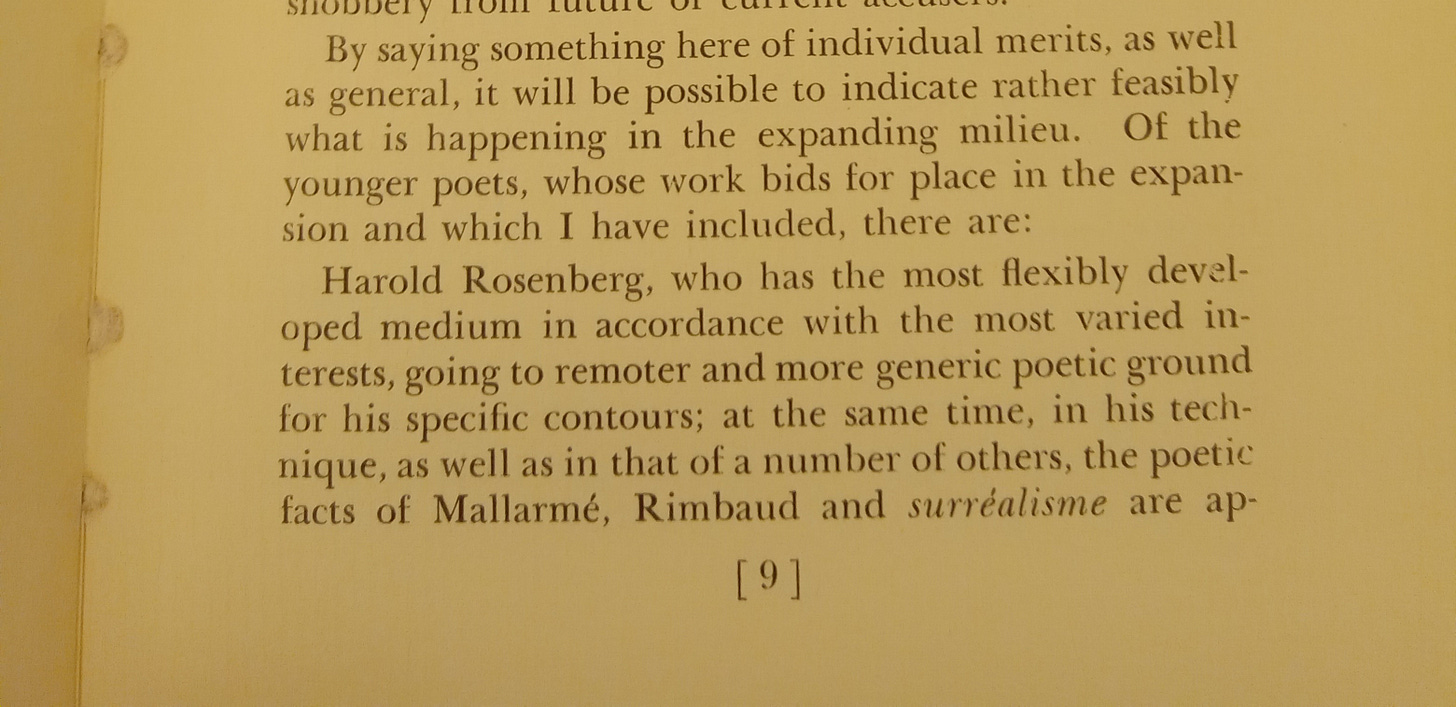

Tyler’s comments about Rosenberg in the intro however aren’t exactly flattering, and maybe betray some unease with how much space he’s given to his friend:

Interestingly—to me anyway—one of Rosenberg’s most stimulating works of art criticism, on his friend Arshile Gorky, praises the latter for deliberately rejecting the idea of originality and developing an art-practice of imitating and recombining styles of living masters like Picasso, Miro etc. I don’t know that I find his argument convincing, but it is a provocative rebuttal to the usual assumption that art (or indeed life) is about the achievement of a unique personal style or perspective.

Parker includes some two dozen pages (!) of Rosenberg’s poetry, which doesn’t exactly reveal him a master of proto-post-modern pastiche. He does seem to have a personal style… of awkward, unmusical plodding—although the content, if paraphrased into prose (which it basically already is), could read as translated Stevens in one case, translated Swinburne (or early Yeats) in another. She’s versatile! But a consistent flop.

It’s encouraging, or maybe discouraging, that Rosenberg, then in his late 20s, would still have another decade and a half to go before he started writing great essays like “The Herd of Independent Minds” and “The Pathos of the Proletariat,” let alone his pioneering art criticism on Gorky, De Kooning, Pollock, etc. I often think God what a lot I’ve time I wasted writing articles on the French East India Company—or these posts!—but some of us only get anywhere limpingly and by detours.

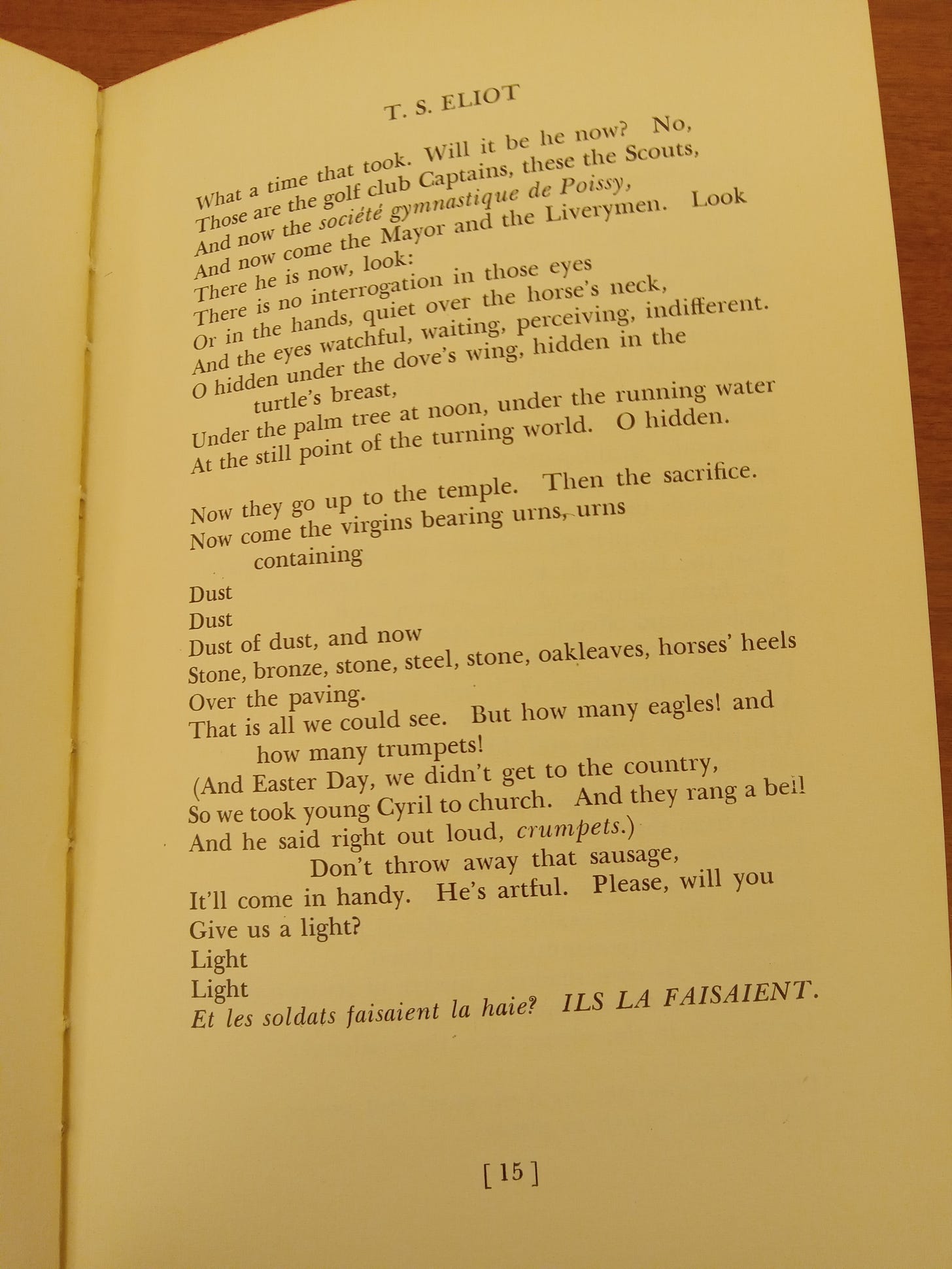

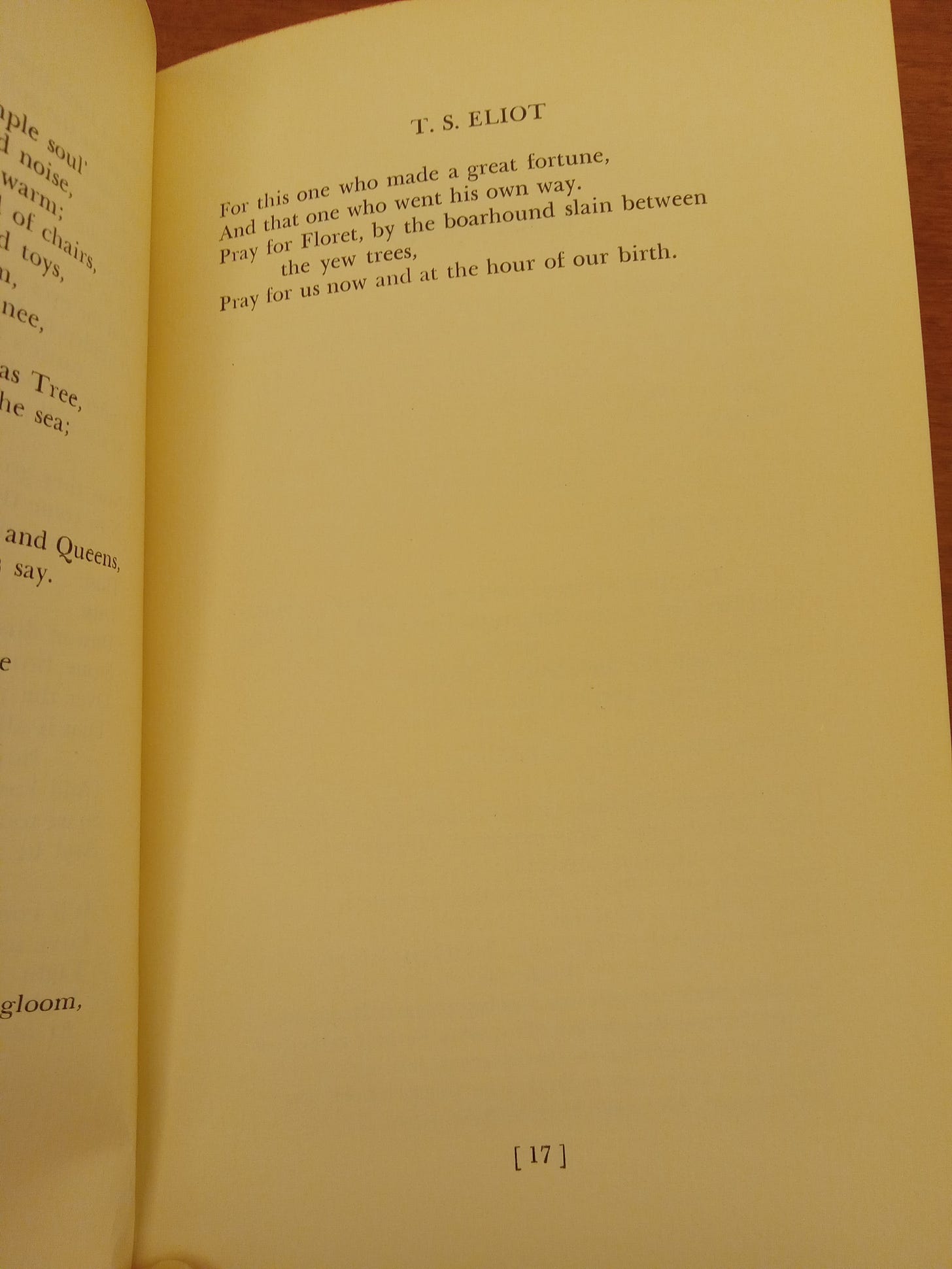

For that matter, I’m not sure I would have recognized Rosenberg as a worse talent than the now-canonical names represented in the same volume, whose work represented in it is often not what anyone remembers today. Eliot, for instance, has top billing in Tyler’s book with these two poems I’ve never heard of:

This is I guess not-uninteresting stuff that kind of reads like something building towards David Jones’ In Parenthesis or the anti-war bits of Pound’s “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” (“There died a myriad…”), which incidentally was my favorite poem as a teen, back when my idols were the pre-Cantos Pound and Robinson Jeffers (she was a serious child). But it of course doesn’t measure up to Eliot’s masterpieces… by which I mean his imitations of Jules Laforgue and the horny “St. Narcissus” (as read by this fancy boy).

I used to have regularly and still have occasionally the anxiety that, being so oriented towards history, whose winners are foreknown, I am deformed away from appreciating the present/future and rightly hailing our own contemporary plausible contenders for the canon, let alone burgeoning writers just at the beginning of great careers—aren’t I likely to miss ‘our’ Pound or ‘our’ Foucault by shitting too hard on Dimes Square or Substack Discourse (although conversely, isn’t it by getting excited about everything that we lose the ability to notice what’s actually good—which isn’t to say the good stuff is what will make it all the way to a possibly retarded posterity! I have no confidence that the history of literature is a slow but ultimately just meritocracy)?

Looking at Modern Things makes me suspect I would have written off Eliot and Rosenberg just as I’m writing off… Honor Levy? Michael Crumplar? Ann Manov? Arx-Han? Frank Cassese? Kai Ihns? Jackie Ess? Geoffrey Mak? Thomas Grattan? to only name some contemporaries whose work I don’t get and/or don’t like. Although who knows what I would have liked—and maybe I’d have been too busy get knifed by a hobo over a crust of bread (this being 1934) to have an opinion. That still sounds like a better way to spend an afternoon than reading In Tongues.

"mid-century free-thinkers who weren’t liberals but also weren’t not to late twentieth-century gay identity rightly understood and legitimated against the whiny critiques of left and right."

I have re-read these lines three times and I cannot figure out what they mean. What are you trying to say here?

Laugh out loud funny: "But all that negativity, that’s the old me talking. The hater. The new me is an enjoyer. She’s thinking about queer interwar modernism and not even minding that it’s also terrible (the secret about literature—gay or otherwise—is that it’s almost all terrible and that, but now I’m talking to myself here, one has to somehow keep this fact in mind without succumbing either to complete pessimism or to delusional cheerfulness that says ‘what do you mean there’s lots of great stuff! Just look at… [and here my interlocutor inevitably names a pile of absolute trash]). "