Ernest Mickler, 1940-1988

a joint monument to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy and the Freedom Fighters of the Sexual Revolution

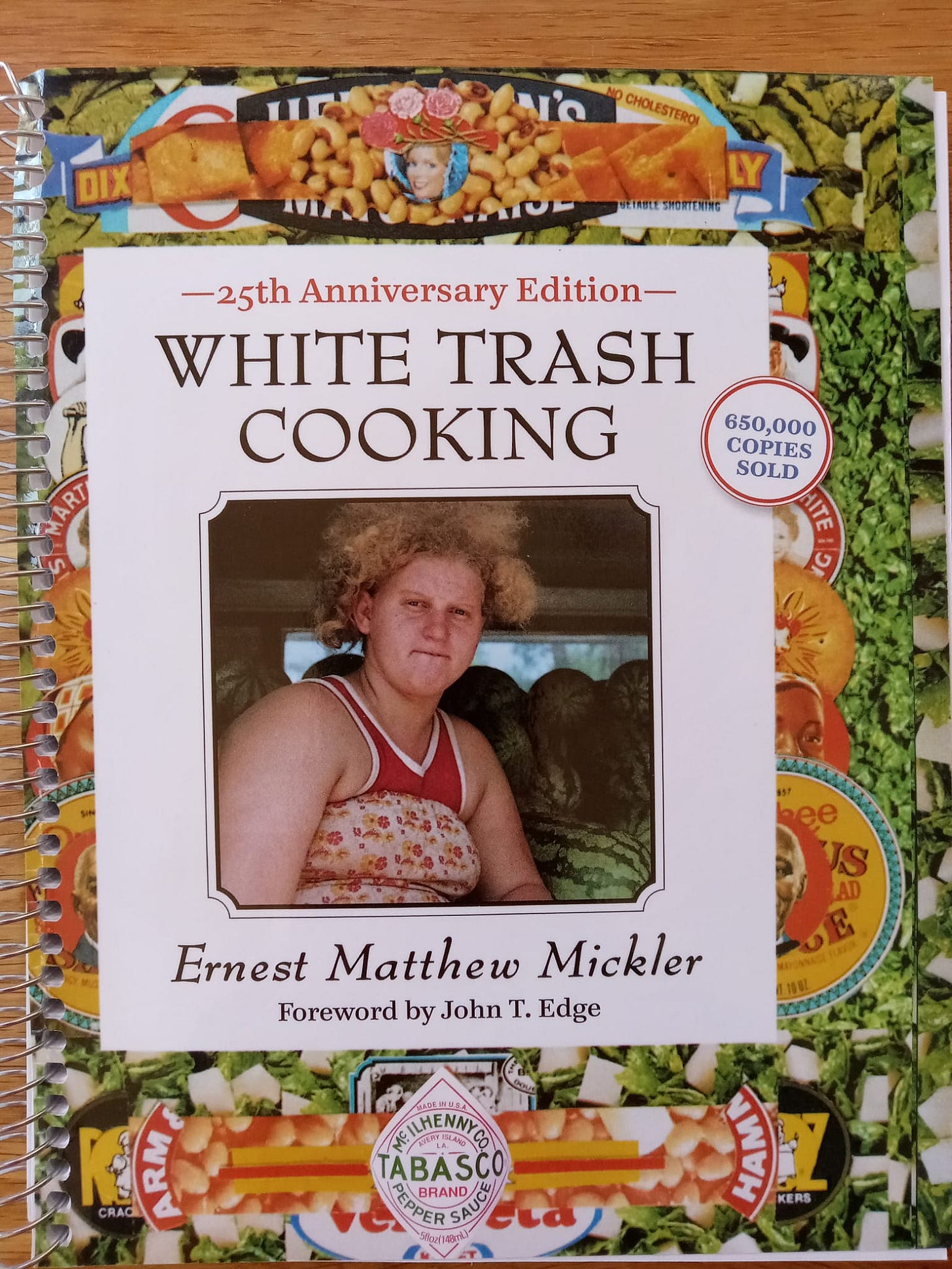

A couple of years ago I wrote an essay on a set of north Florida gay writers for the print-only publication County Highway—which, I take it, nobody read! Since then I’ve posted here from some of my research on one of those writers, Cal Yeomans. Today I’m sharing the whole essay (below), and (before that) some excerpts the work of another of the writers profiled, Ernest (Ernie) Mickler, who published, before his death of AIDS in 1988, two very camp ‘White Trash’ cookbooks, which besides the recipes also feature photos and stories.

After a little over a year and 100+ posts (!) writing about various semi-obscure gay writers, artists, critics, etc., which have found (present company excluded) more or less no audience, I’m thinking that perhaps there isn’t, and isn’t going to be (at least not here), a public for the sort of work I’ve been doing along these lines: trying to think about the cultural/intellectual affordances of certain genealogies of gay history that look to me more expansive and fun than those otherwise on offer. They seem to find about as much of a readership as last fall’s long-in-the-making little-read essay on Judith Butler that I meant as my farewell to thinking about gender. So once I finish posting, in mid-summer, a dozen or so more upcoming (already written) items about Michael Denneny and his Arendtian praxis of gay criticism, I’m going to put my energies elsewhere and just leave this up as an archive of sometime interests.

But I do love this stuff, and if there were money or even not much money but merely a decent audience in it, I’d love nothing more than to be writing only about it, in the hope that sort of loving criticism would generate culture-making energy for myself and others—and to show that there’s a way to talk about gay things without the cringing self-defeating excuse-making of so many gay male writers, from commie scolds like Ben Miller to tradtards like Stephen Adubato to the sad excuse for liberal homo-humanism served up by Ben Moser. We can do better, we have been better, we are better! Some of us anyway.

Well, I’m rantingly getting in the way of Mickler. Here’s White Trash Cooking, vol. 1:

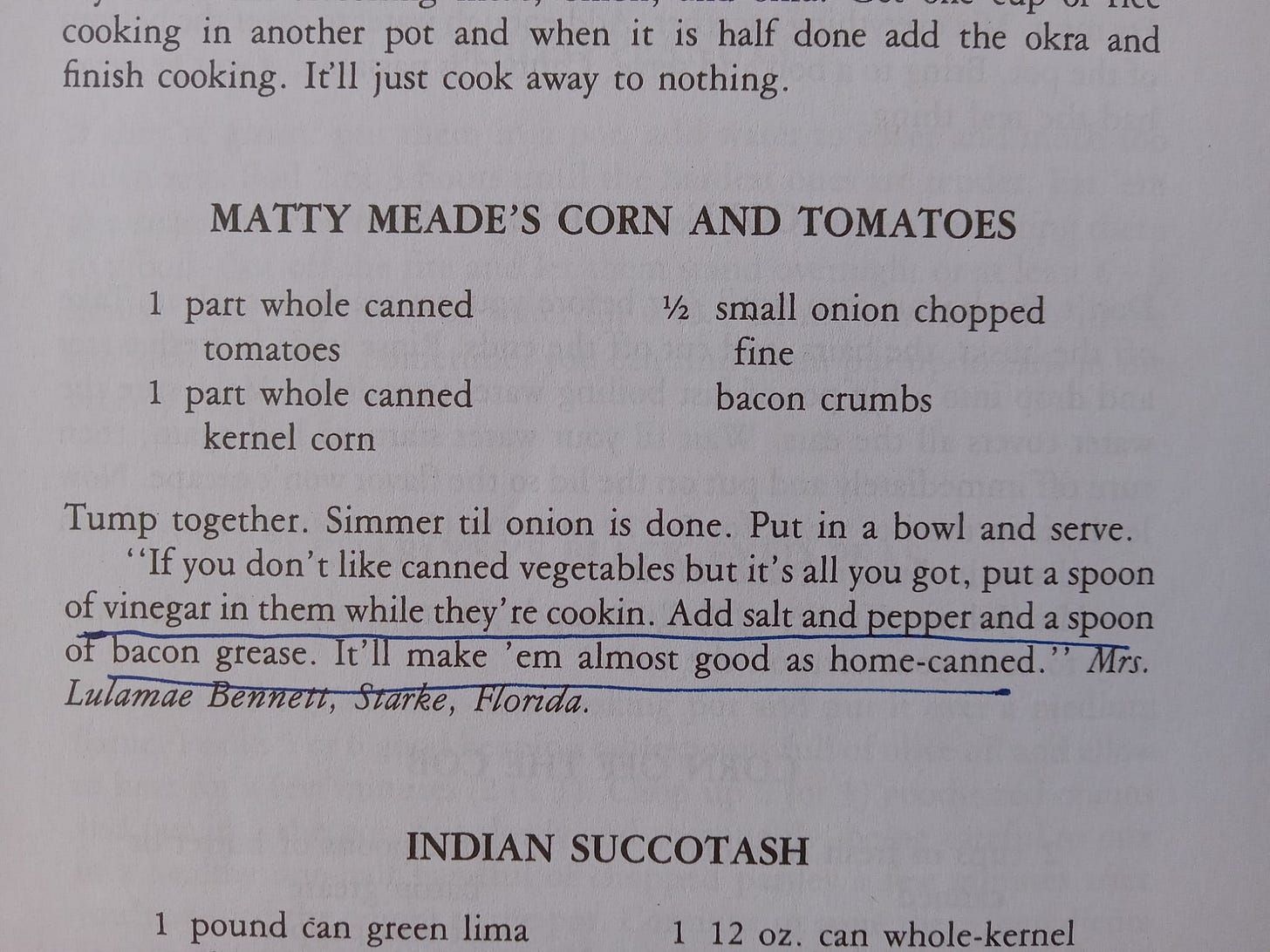

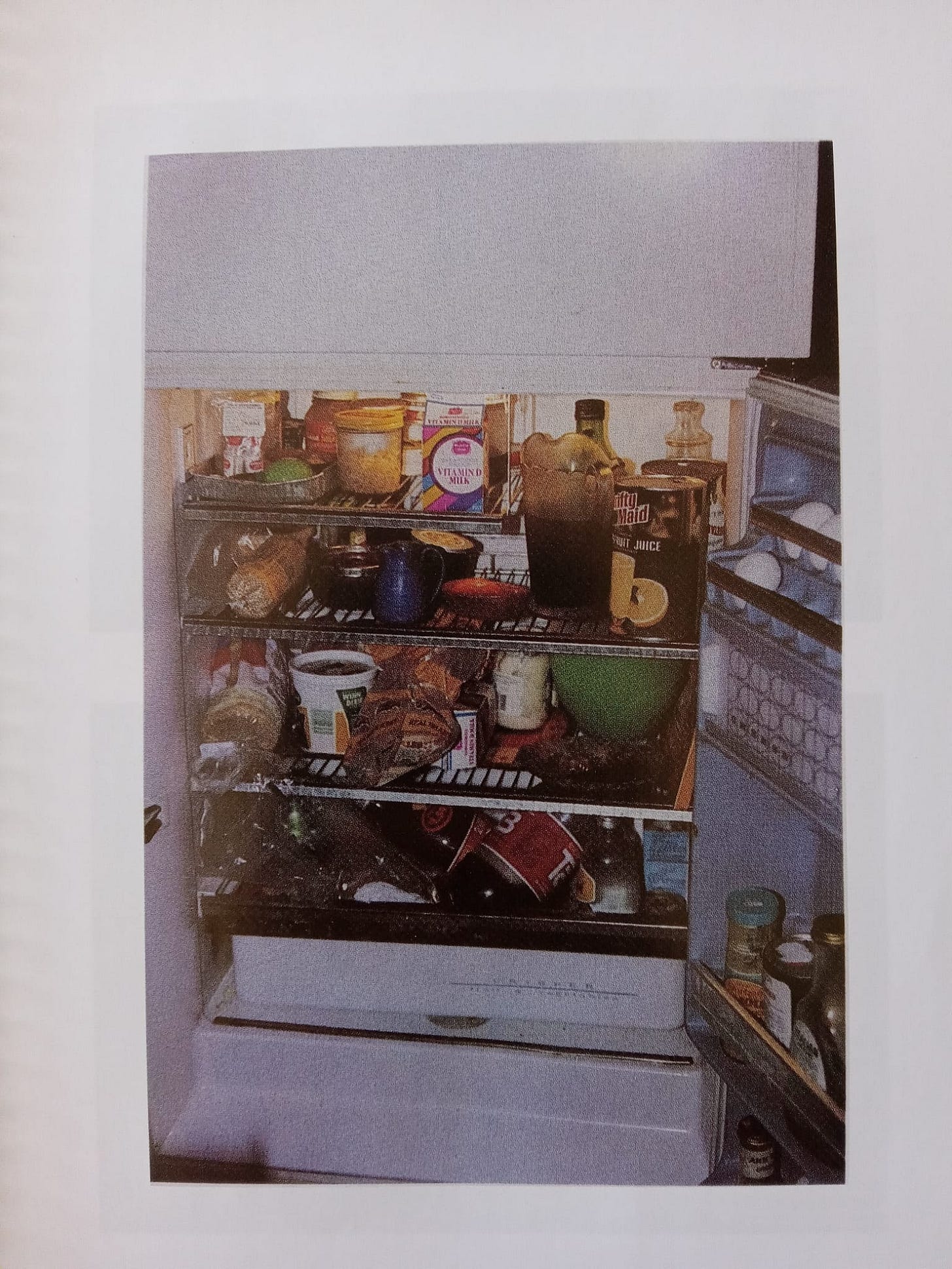

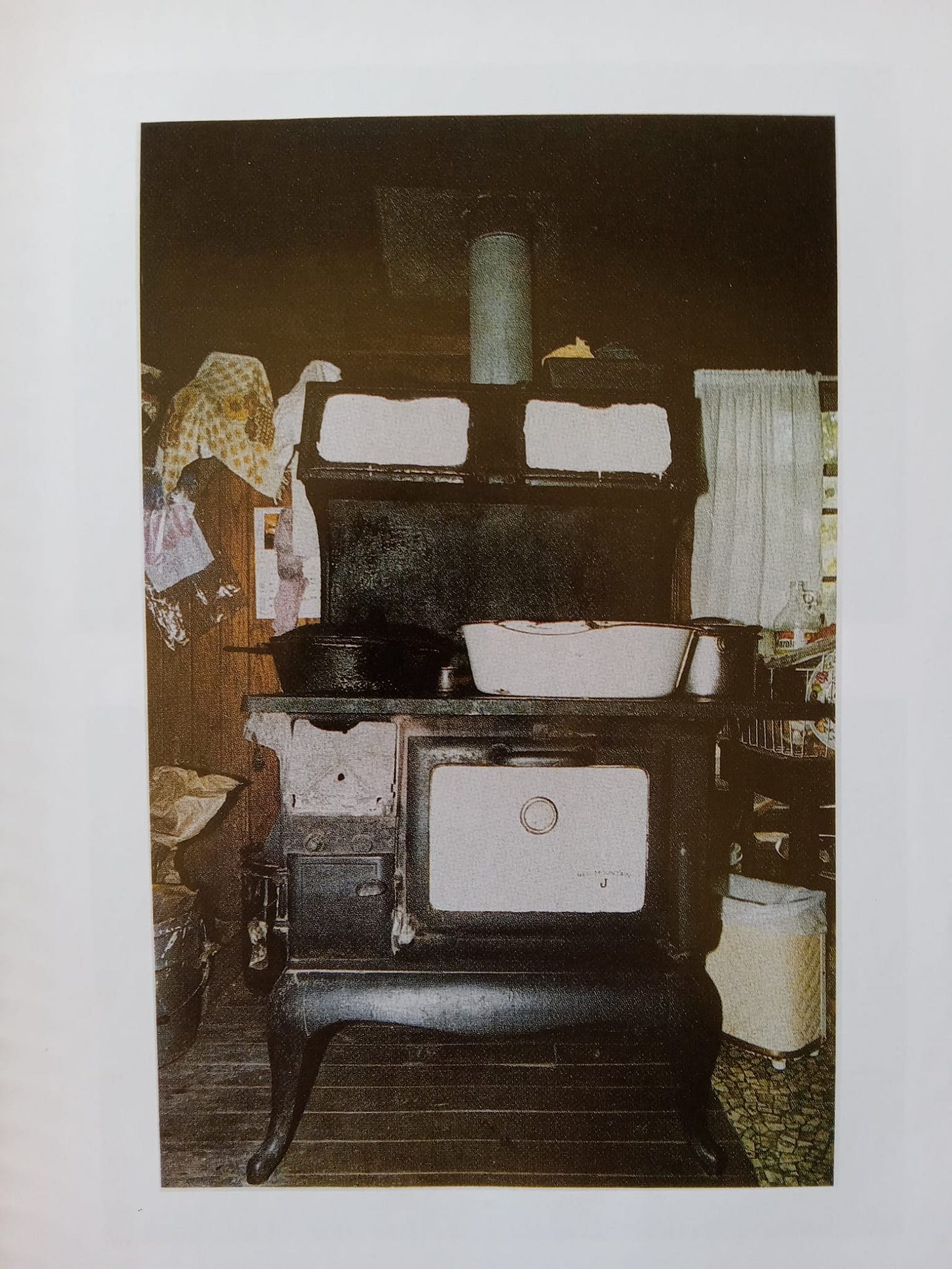

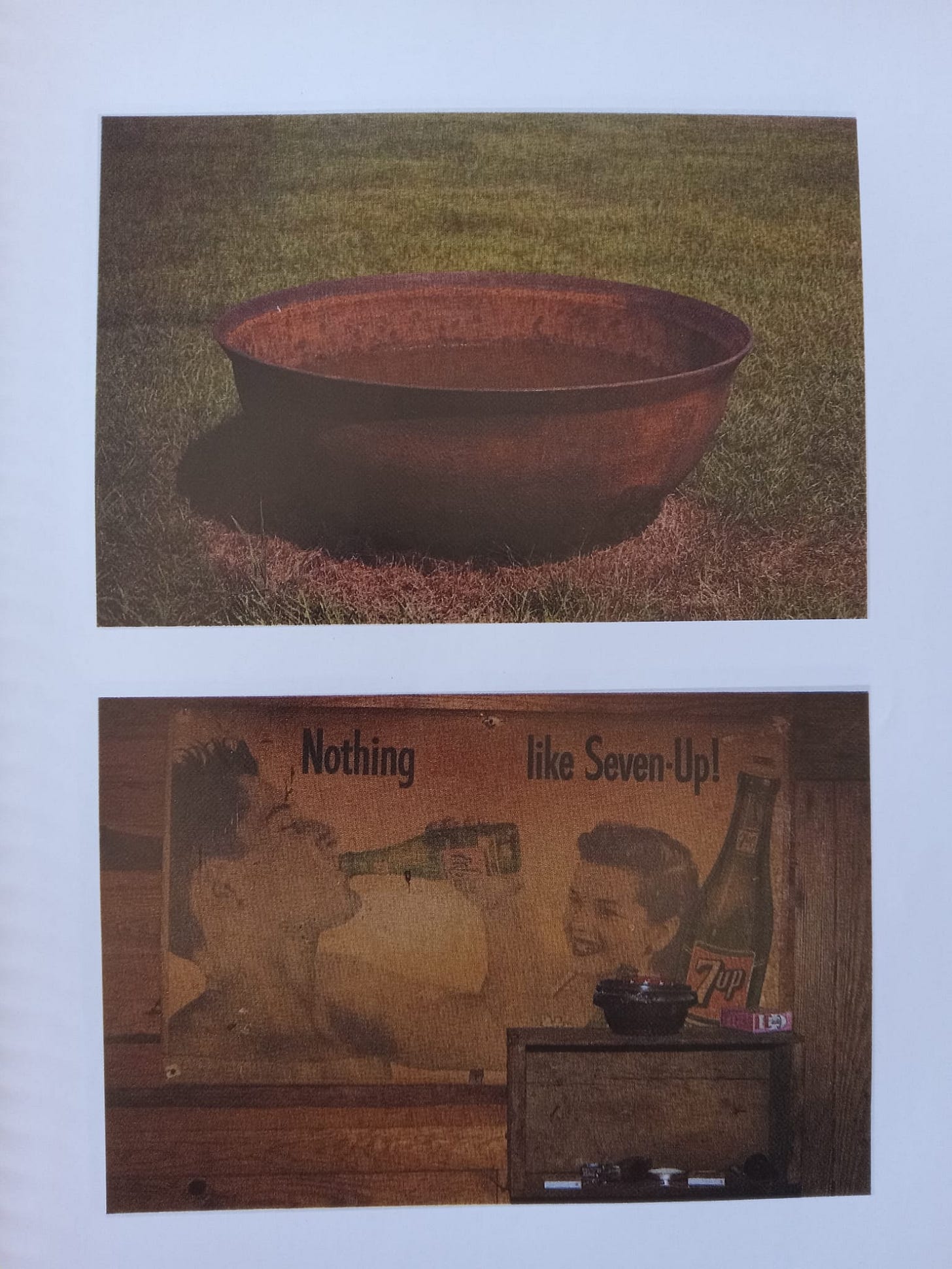

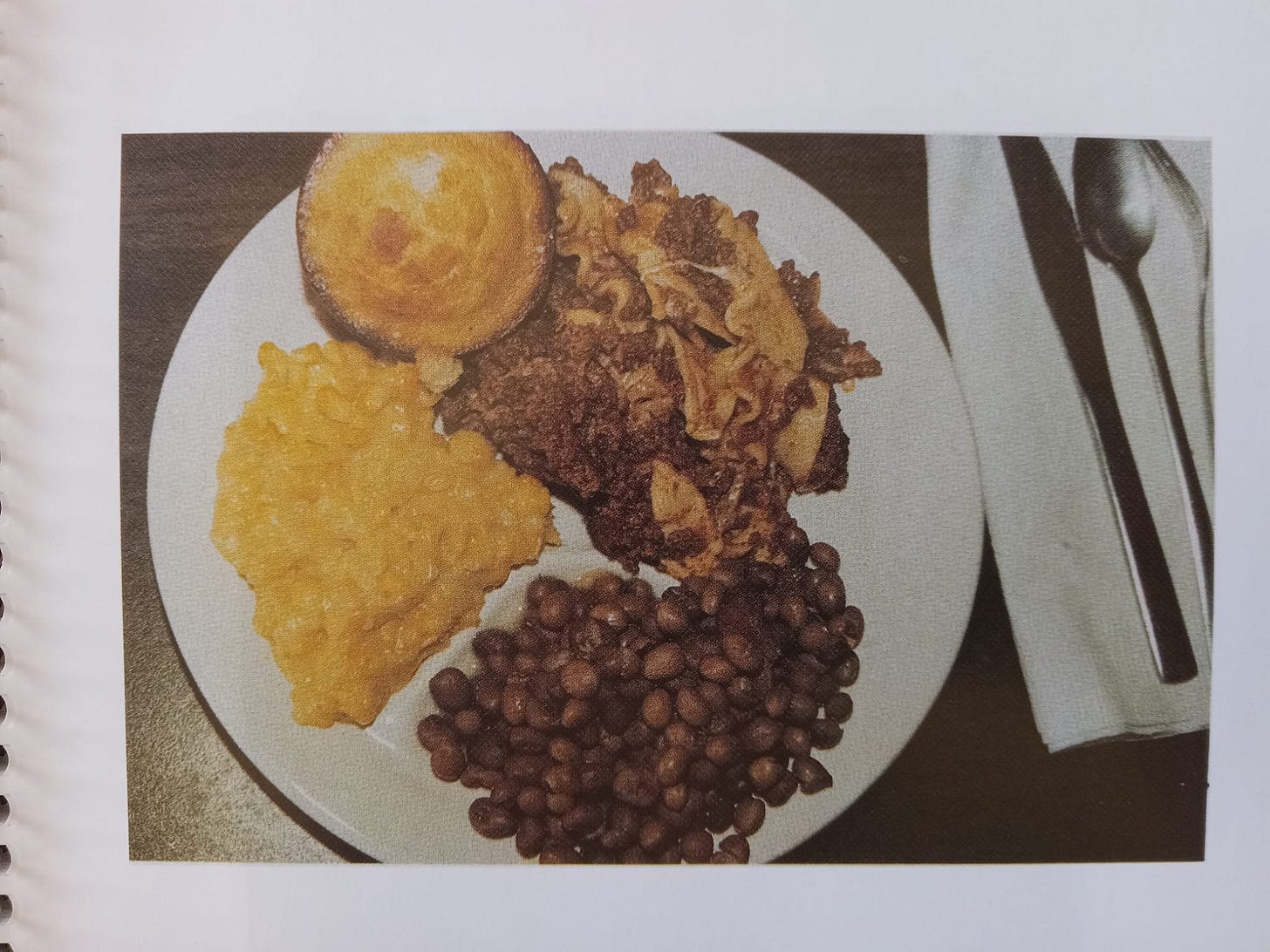

Just a few of the recipes and photos—things that remind me of my own Mississippi family:

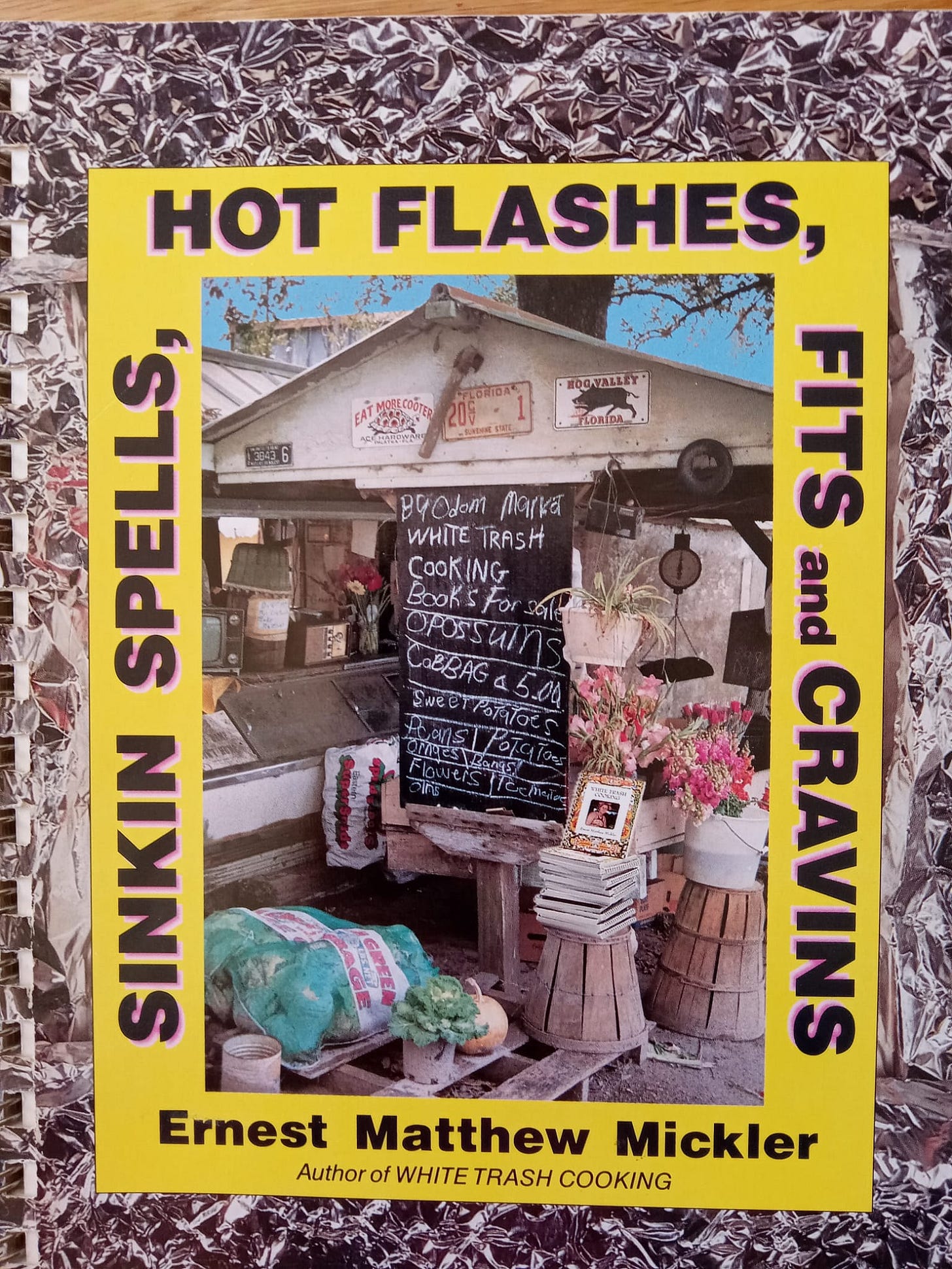

And the sequel, which is where Mickler, dying, included some charming stories in dialect:

My essay below…

***

North Florida may not seem a promising site for a literary scene—for one thing, it’s awful humid—but forty years ago the Gainesville area was home to a set of trailblazing gay writers who drew on the traditions of southern literature in innovative and sometimes shocking works. At its center was the playwright Cal Yeomans, a Florida native who returned to the area in 1978 after years in Atlanta and New York. There he befriended Ernest (Ernie) Mickler and Andrew Holleran, writers who in different genres used the resources of gay and Southern culture to write hilarious, horny, and heart-rending dramas, novels, and—wait for it—cookbooks.

Yeomans, born in 1938, was the senior figure—although in 1978 he had little aesthetic achievements to show for his forty years. He had spent the previous decade unsuccessfully trying to make it in the world of avant-garde theater, writing absurdist, one-dimensional shock-mongering stuff about drag queens and transsexuals in the spirit of Andy Warhol’s films (and a lot of embarrassing confessional poetry). In the two years after his return to Florida, however, he would write a series of controversial plays that shook the burgeoning world of gay theater when they were performed in New York and San Francisco.

Richmond Jim (1979) shows a young Southern man’s journey north, into the gay leather subculture and ends with a cockring being slipped around his member by his more urbane lover, who, in a move familiar to pushy bottoms everywhere, declares himself Jim’s sex slave. Sunsets is (1980) still more outrageous: a trilogy of plays set in and around a rural Florida beachside public restroom cruised by tragic old queens (including an ancient leather daddy with a walker and catheter), a ‘straight’ guy in denial (his wife is waiting outside!), and two guys who might fall in love.

The plays depicted gay life far removed from the world that was being created in coastal metropolises. Some reviewers glowered at their staging what seemed like such tragically degraded representations of homosexuality, and others patronizingly found that Yeomans had shown the plight of backwards benighted denizens of fly-over America. As gay historian Jay Watkins has noted, Yeomans himself was ambivalent about what his plays ‘meant,’ making different statements in his letters and diary entries. He hadn’t made up his own mind whether Richmond Jim was meant to celebrate or satirize BDSM as a new urban mode of sexuality, whether its protagonist was right to shuck off his hayseed innocence and embrace uninhibited libertinage, and whether the characters of Sunsets were doomed pariahs to be ignored or pitied by coastal viewers.

The strength of the plays, in fact, is that they thrum with uncertainty, most intensely in the scenes where Southern queens vent soliloquies to rival those of Blanche Dubois. In Richmond Jim the title character’s seduction, is interrupted, in the middle of a vigorous nipple-squeeze, by an “apparition,” announcing herself as “La Countessa de Hosenvilles.” It’s Biddy, a middle-aged queen from Atlanta who’s somewhere between rural and urban, tragic and ridiculous, male and female—wearing a Marine’s coat with a big black 1930s woman’s hat and high heels. Biddy plops himself down and declares that things are getting worse “than Emma Bovary ever thought possible.” A litany outrageous complaining (guys keep asking him to drink their piss!) cockblocks the couple for a full third of the play, and when his exit at last return the mood to semi-pornographic seduction, viewers or readers are left to wonder what Yeomans had meant to achieve. Is Biddy—compellingly bitchy in a Quentin-Crisp-crossed-with-Truman-Capote way—there to deflate the eroticism, to ironically comment on it, to undo the pretenses of pure mutual masculinity that the leather-sex scene relies on? Who knows, but it sure is funny!

The same year Yeomans arrived in Florida, Andrew Holleran published his epochal novel Dancer from the Dance, which recounted his move in the opposite direction from Richmond Jim—down from New York to rural Florida—as a Great-Gatsby-esque tale of a young man becoming disillusioned with the emerging gay male New York subculture that ran from the city’s discos and bars to Fire Island. Yeomans and Holleran would become friends, with Yeomans supplying photos for Holleran’s column in the gay magazine Christopher Street, which broadened its horizons to include small-town gay life. At the same time, Yeomans befriended Ernie Mickler, another gay Florida native who had returned home after living on the West Coast.

Today, of the three writers, only Holleran’s work—soon to be republished in a new edition later this year—is well-remembered, chiefly as an emblematic novel of modern gay literature. Dancer from the Dance, and his masterpiece, The Beauty of Men (1996), which shuttles between Florida and memories of New York, are hardly ever cited as Southern novels, despite their settings and Holleran’s avowed debts to Tennessee Williams, whom he has discussed in some of his critical writings. Dancer begins, in a letter parodying Williams’ stage-directions and his tragic heroine’s monologues:

“Midnight. The Deep South.

Ecstasy,

It’s finally spring down here on the Chattahoochee—the azaleas are in bloom, and everyone is dying of cancer.”

Who could deny these three sentences their rightful place atop the Podunk Parnassus of Southern letters?

Holleran chronicled his life in Gainesville in essays, novels, and short stories, in which Yeomans regularly appeared either under his own name or as the character ‘Roy.’ After the controversial success of Sunsets, however, Yeomans disappeared from gay theater and wrote little. As the AIDS crisis erupted in 1981, Yeomans’ brand of sexually charged dramaturgy was less and less appealing to directors and audiences. His plays, never published, were largely forgotten, and his legacy has only recently been revived by scholars like Watkins and Carl Schanke, and the Chicago theater director David Zak, who is staging a version of Sunsets this winter (one wonders what Ron DeSantis and Chris Rufo will make of it!).

Yeoman’s life could be told as one of failure. Between 1981 and his death from AIDS in 2001, he wrote little polished material—a brief scene set in a gay bar, in which a man confronts his AIDS diagnosis; an unfinished sequel to Sunsets; a few short stories—nothing of the caliber of his earlier work. But he had a sort of second career as an artistic collaborator, supplying photos for Holleran’s column and offering mentorship to the younger Mickler, who had returned to north Florida after living in New Orleans, California and Key West. Like Yeomans, Mickler had tried to make his name as an artist (after a stint as a country singer) and had spent the 70s writing terrible poetry. Like Yeomans, too, he began to find his voice as he returned to his native soil and to Southern subjects.

In the mid-1980s, he started turning his collection of recipes and photographs collected from travels around the South into a cheeky cookbook, White Trash Cooking, a title he refused to let go of, although for years one mainstream press after another told him it was offensive, stupid, and sure to tank sales. When it was finally printed in 1986 on Jargon Press—mostly known for publishing the poetry of the Black Mountain school—it became a surprise best-seller.

White Trash Cooking begins with an introduction distinguishing “white trash” from “White Trash,” poor folks with no “pride” from the ones who’d been raised right. White Trash won’t sit “on a made-up bed” or open “someone else’s icebox;” it’s apparently better not to mention what white trash, lower-case, will or won’t do. Mickler admits this is a tenuous definition, but then, if you’ve got no money, and nobody in your family does either, then you’ve got nowhere but definitions to put your pride.

The South itself, he goes on, is a living myth Southerners have made together out of “legend on top of legend on top of legend,” from stories in which we remind each other that “our good times are the best, our bad times are the worst, our tragedies the most extraordinary, our characters the strongest and weakest” (Of course many ethnic groups like to imagine themselves as ‘like everyone else, only more so,’ as exemplary members of humanity whose emotional intensities and gift for narrating them outshine, but reflect back upon, the humdrum everydayness of soberer peoples, whom they might call whites, gentiles, gringos or yankees. It’s just that Southerners happen to be right). And a story needs a meal.

White Trash cuisine is not quite Soul Food, Mickler insists, although they are “kissin’ cousins,” and it’s certainly not the high, fine, Frenchified cuisine of Old South plantations memorably celebrated in William Alexander Percy’s memoirs Lanterns on the Levee (1941) and still served in expensive restaurants from New Orleans to Charleston. White Trash cooking means cornbread (“made with pure cornmeal”) and salted meat (“bacon or ham”) at every meal, lots of frying and black cast iron pans “that give you that real White Trash flavor and golden brown crust.”

Many of the recipes in White Trash Cooking are real enough tastes of that flavor, honed from Mickler’s family traditions and his work as a caterer in Key West—although others, like the oven-baked possum, are hopefully jokes (on the other hand, having myself seen cousins fry squirrel in backwoods Mississippi, I must confirm the authenticity of his recipe for that delicacy). Real or not, each one is a little poem, with cheeky asides to the reader (“while they are hot you can roll them in sugar, if you feel like it”) and quotes from the characters who provided the recipes (“No picnic is a picnic less’n you have a banana puddin”).

They were, indeed, edited and published by the avant-garde poet and North Carolina native Jonathan Williams, whose correspondence with Mickler is as much a delirious homage to the cornpone as White Trash Cooking. Williams often addressed Mickler with nicknames like “Cousin Crisco” and “Cousin Gator,” items of cookery that can be found in Mickler’s book, and jokingly related to him as a fellow Southerner and gay man. Shortly after White Trash Cooking was published, as Mickler hesitated on what should be his next project, Williams announced to him (“Just Plain Bubba”) that he had applied (unsuccessfully, it would turn out) for a Guggenheim fellowship on his behalf: “they fucked up back in the 1930s and never ever gave a grant to Arnold Schoenberg… I told them they better not fuck up this time, for sure, or we’d see to it that they had to sleep in the same bed at night with the editor from The New Yorker.”

In its combination of high jocular just-plain-folks pantomime (‘ain’t nothing but us rednecks down here!’) and pedantic pretentiousness (reminding the Guggenheim they had misjudged modern music and were likely to miss their chance on an eccentric folklorist too) meant to baffle and outdo the hated Yankee, who somehow has more money and prestige than us despite being less folksy and less cultured, the letter was a model of a certain strain of Southern writerly resentment for everything expressed by the unbeddable New Yorker.

But of course the Yankee is also courted, even as far as New York—and wooed in Mickler’s case with great success. White Trash Cooking sold hundreds of thousands of copies, with warm reviews everywhere from the New York Times Book Review to Vogue. Mickler was briefly a celebrity, appearing on the David Letterman show, and worrying, in private, how to follow up on his best-seller. He wanted, in whatever form the sequel took, to include not only more of the photographs of the Deep South that made White Trash Cooking so charming, but also to include stories from the people his recipes were drawn from.

Mickler had been studying up on his Southernisms ever since he returned home from California several years prior, and filled a notebook with picturesque expressions picked up in his travels around the region. Some of these strike a Southerner—that is, me—as entirely familiar and even unremarkable: knee high to a grasshopper, slow as molasses, high-tail it, betwixt ‘em, sugar tits, I don’t know him from Adam’s housecat—but it was this careful attention to local speech that allowed Mickler to begin writing convincing fiction set in ‘cracker’ north Florida. In unpublished stories apparently written in the early 80s like ‘Keep Your Hats On’ and ‘Tetch o’ the Monkey,’ he experimented with language and local color, even as he compiled the recipes of photographs for White Trash Cooking.

Mickler seems to have initially planned to capitalize on his cookbook’s unexpected national popularity with a stage musical—something like a countrified Pumpboys and Dinettes organized around various scenes of cooking and eating, from family reunion to funeral. Yeomans, with his experience as a playwright, was to help him in the endeavor. But Mickler was soon diagnosed with AIDS, and would die within two years of White Trash Cooking’s publication, in late 1988. Rapidly weakening, he used the time left to put together a sequel, Sinkin Spells, Hot Flashes, Fits and Cravins, completed just days before his death. Although its format was similar to White Trash Cooking, with recipes and photos bound in a homey-looking spiral, Sinkin Spells grouped its recipes for specific occasions (“Hawg Killins,” “Foot Washins,” etc.), each with a story.

Some of these are comedic gems, like “Christmas Shoppin,” in which little Juanita asks her mother for a recording of Madame Butterfly. Her flabbergasted mother, who has no idea who or what this is (“Why who sings it honey… Dolly Parton?”), is made to hear the plot, (“It’s about a soldier… that falls in love with one of them Japanese women…) at the end of which she knowingly declares, “She ougthen to shot that son of a bitch right in it. I tell ya, sometimes they are all alike… But, honey, them mixed things ain’t never worked, any ways. That’s proof-puddin.”

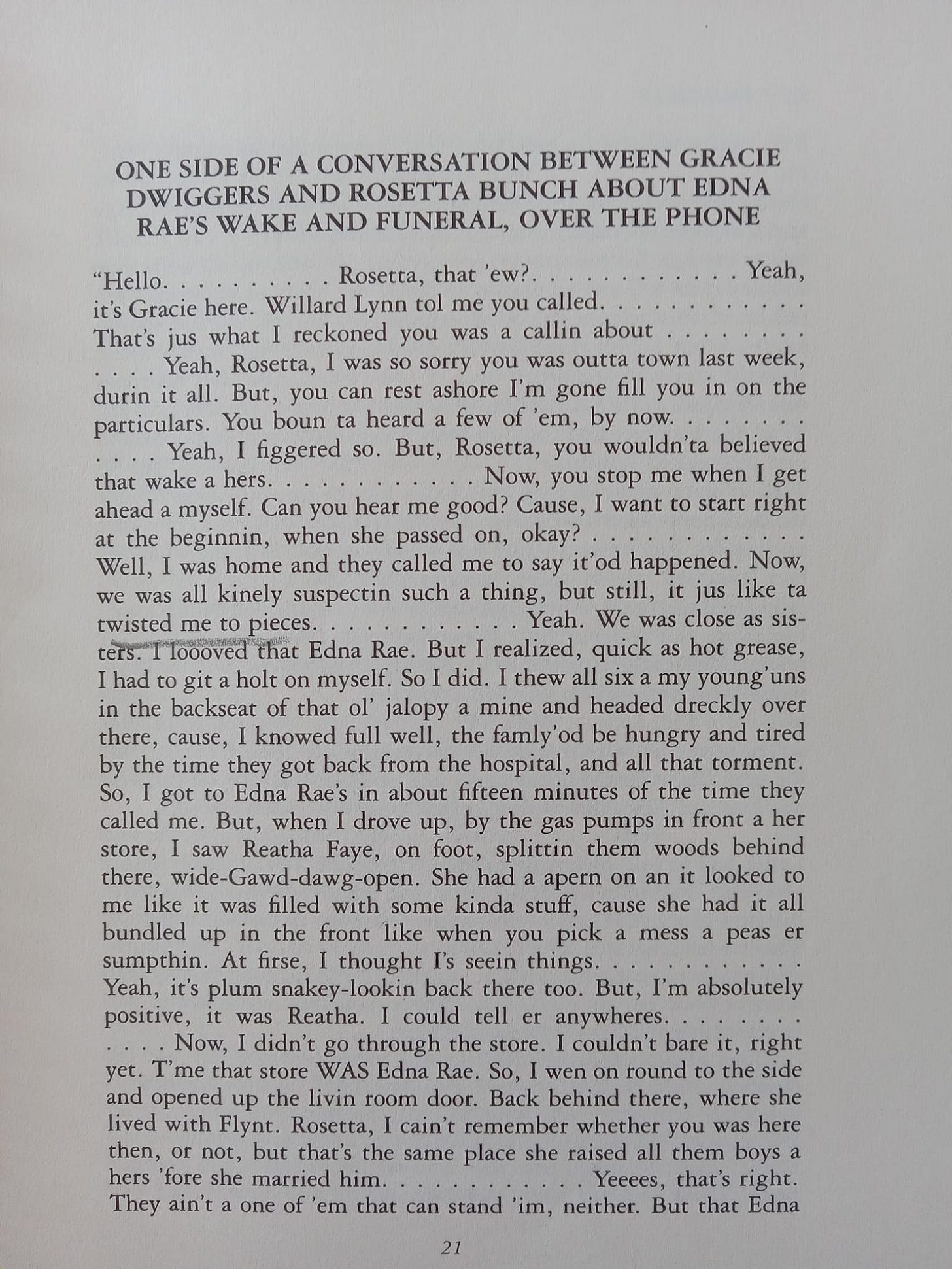

Others are just as funny but also sadly poignant. Perhaps the best of them is “One Side of a Conversation Between Gracie Dwiggers and Rosetta Bunch About Edna Rae’s Wake and Funeral, Over the Phone,” which both showcases Mickler’s ear for dialect (“Now we was all kinely suspectin such a thing, but still, it jus like ta twisted me to pieces”) and growing ability to play with form (the story as a monologue told into the phone), is also a vivid portrait of grief, written as Mickler himself was dying, along with many members of his gay world.

In an essay for Christopher Street, Andrew Holleran described Mickler’s last hours—the priest who gave him communion wore rubber gloves—and funeral, for which Mickler had “planned down to the music and food,” catering to the last (“There is not too much mayonnaise on the cole slaw, the pork is perfectly done… A memory of Ernie is a memory of food.”)

Holleran made a point of reminding the readers of Christopher Street, marketed to urbanite gay men for whom places like rural north Florida were most often only a bad memory or a stereotype, that “Pride”—now with a capital P, the Pride behind which gays had learned to rally—was what separated white trash from White Trash in Mickler’s mind. And White Trash Cooking had been an expression of pride, even if many readers, outraged in the South or amused in the North, assumed it was “a send-up; rather it walked a fine line… offering these memories, these manners, these recipes, just as they are; and by offering them, with such honesty and charm that—like an alligator whose throat is stroked, one fell under their curious spell.”

One the one hand, honesty—portraying the life of put-down, maligned people truthfully, in their speech and action, holding back from nothing out of prudish concern for respectability. On the other hand, charm—using all the artifice available to cast that truth in such a way that the reader sees those portrayed, in all their abjection and grotesque and sometimes clownish misery, as not only worthy of sympathy but as funny, cagey, sharp-tongued interlocutors who need nobody’s Lady Bountiful benevolence. This difficult double demand was the tightrope walked by Southern writers from Williams and Faulkner on down, and from the pioneering generation of gay male writers of whom Holleran was the most talented and thoughtful member.

Mickler and Yeomans were painfully conscious of the task that confronted them as self-awarely Southern gay writers. In a letter to Mickler written as he was preparing the stories for Sinkin Spells, Yeomans warned him: “Much of what you write is in the vein of ‘Southern grotesque’… Be cautious or as I’ve done many times and had to work hard to get away from, you’ll find you are writing about a cliché.” Yeomans didn’t say which of his plays he felt had fallen into the lamentably predictable patterns set by writers catering to the prejudices of Yankee audiences, but his concern about this may have been part of what contributed to his long writer’s block after his return to Florida, especially as the AIDS crisis made representing gay life a gravely political challenge. But he remained (this may have been just his trouble) a keen critic, alert to the traps that lay ahead of Mickler as he struggled to wrest a second book from the few months left to him. “I KNOW it’s full of quicksand,” he concluded.

A year later, with Sinkin Spells barely finished and Mickler on his deathbed, Yeomans interviewed him in a staggering day-long conversation that takes up over one hundred single-spaced pages of transcript. There was a lot of gossip—who’d screwed whom, and who’d been screwed by which publisher—but the main theme of their talk was the problem Holleran had hit upon: how to write honestly and compellingly, with realism and charm, from a southern gay perspective.

Neither of Mickler’s books has an obviously gay content, although there are tongue-in-cheek references to meals “fit for a queen.” But he insisted to Yeomans that he kept his work right “on the line” between realism and a form of verbal play he’d learned from sass-mouthing gays. He saw his book, which apparently had nothing to do with gay people, as a product of “gay culture,” from which he learned the arch art of making “a humorous remark about just about any tragic little thing that happened.” Nasty “old queens” can be “just awful and tacky…calling people Mary and all that shit, but I think it really sharpens your mind.” Being cruelly, woundingly funny and enchanting bleak situations with preposterous exuberance were skills the writer should learn from gay life.

Mickler learned from old queens and great authors. The most important of the latter for him was Zora Neale Hurston, the African-American novelist and scholar who had grown up in central Florida (“she walked on the shell ground I walked on”) and whose papers—like Mickler’s and Yeomans’ today—are held at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Mickler worked through them, reading her drafts and correspondence “in chronological order… like a biography,” learning from her how to capture local dialect the way she had in Mules and Men (1935) and Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). In contrast, he’d couldn’t stomach Faulkner, whose dense, long-winded, modernist experimental prose has certainly marked American literature from Shelby Foote to Cormac McCarthy, but is far from the combination of earthiness and camp Mickler wanted to capture. No one has ever to my knowledge spoken of Faulkner’s charm.

As with Mickler’s notes on local phrases that caught his ear, his study of Hurston shows that his decision to “write Southern” was by no means a matter of simply being himself or writing things as they were, but a painstaking effort to learn both about Southern realities and about the traditions of representing them—which meant learning from the great African-American writers how to write about White Trash.

With such a sensibility, Mickler might seem to be an ideal candidate for the kind of politically correct revival that forgotten artists from marginalized groups are now posthumously granted by urban liberals and their Southern imitators. Indeed he was profiled not long ago in The Bitter Southerner, a publication whose title tells you what you need to know about its politics, by Michael Adno, who concludes what is otherwise a lovely and urgent tribute to a now sadly neglected writer musing thus: And for many, I believe Ernie forged a portal into the South — a South unto itself — proudly bound up in all its contradictions. He helped Southerners of all strata hold onto their roots, spanning the spectrum from blue-blood aristocrats to rednecks. But more specifically, he helped queer folks find that root in a place that — particularly during the AIDS plague of the 1980s — wanted to expel them.

Now one might graciously ignore that strata do not have roots and that portals are not quite forged, and even that Mickler and Yeomans were not (in the cosmopolitan parlance of MFA-holders putting on a bit of faux-folksiness) “queer folks” but gay men—but Adno avoids what “pride” really meant to Mickler. The South was not just a place that “wanted to expel” him, but a place he was from, returned to, and carefully studied so that he could give it voice, a voice that speaks out not only or even primarily against local failures and sins or even against the contemptuous outsider but of love of one’s own.

Discussing the problem of how to write in the face of Yankee condescension and rejection—many Northern publishers had turned down White Trash Cooking before Williams made a fortune with it on his own small press—Mickler recommended Yeomans listen to “that song about Lester Maddox [and] some smart ass New York Jew” by Randy Newman. That song, ‘Rednecks,’ with its tongue-in-cheek refrain (“We’re rednecks, rednecks/ We don’t know our ass from a hole in the ground/ Rednecks, rednecks/ Keeping the n-----s down”) remains a staple of a defiant white Southern-ness that affirms, with a tetchy, self-dramatizing irony, that we’re exactly what progressive Northerners think we are (Newman, of course, a master of ambivalence, was himself Southern and Jewish, and goes on in the song’s final verse to argue that the Northerner is the real racist).

Here’s how Mickler expressed his own unapologetic view of the “contradictions” of the South: You know I’m not a Rebel as far as like a Southern Rebel, like a lot of people are waving the Rebel flag and all that, but I had a grandfather who was a captain in the Civil War and a great honored scout for the South and I mean I’m glad they lost, but I can’t discard his honor… I don’t think Yankees can understand that.

Yeomans responded that he felt the same way about the generation that had led the Sexual Revolution and Gay Liberation. If AIDS seemed to many observers to have disastrously disillusioned utopian hopes for a transformation of sex into something joyous and free, Yeomans was unwilling to see the dead as mere victims. They had “fought a war and been a casualty of that war, which I think that too, will be honored as such, in some way.” There are few writers, critics or just plain people today who can hold the Lost Cause of the Confederacy and the Freedom Fighters of the Sexual Revolution together as what theorists like Judith Butler whinge about as “grievable lives,” and fewer still who can insist that our response to loss anyway isn’t grief or trauma but honor—and honor that doesn’t commit us to any ignoble meanness, like wishing we’d won the war and kept our slaves, or refusing to learn from black authors like Hurston who can teach us, precisely, how to be white Southerners and proper writers. In what from the perspective of 2023 seems an impossible conjuncture, monuments to the Confederate dead and a future AIDS memorial appear together as means of honoring those who lost doomed wars in that “immoderate past” (as Allen Tate called it) and whom the whole delicate tight-rope-walking art of southern, gay, and indeed American literature is a learning rightly how, with neither chauvinism nor regret, with truth and charm, to praise.

“Anyway,” Yeomans concluded, “we keep veering away from ‘White Trash,’ the story of the book.” “I don’t think so,” Mickler answered, “This is all part of it.”

I’ve been able to understand my history better through your re-discovery of some folks on the front lines of the everyday-gay (at least as seen through your often hilarious lens). Thanks.

I’ll be sorry to see this end, I’ve found it fascinating!