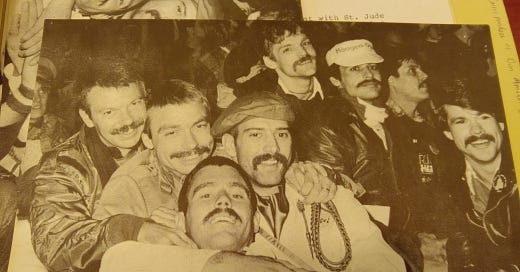

Amador and friends with compulsory period moustaches

Last week I was in William & Mary in Virginia, looking at the papers of Don Amador (1942-1992), a pioneering figure in gay activism and Gay Studies who has, as far as I could figure out, no connection to the college or the state—I have no idea why his stuff was there! One of those boring mysteries of historical/archival research—although it has the serious consequence that neither the college’s gay historian nor its queer archivist knew of or about the papers… or really who Amador was.

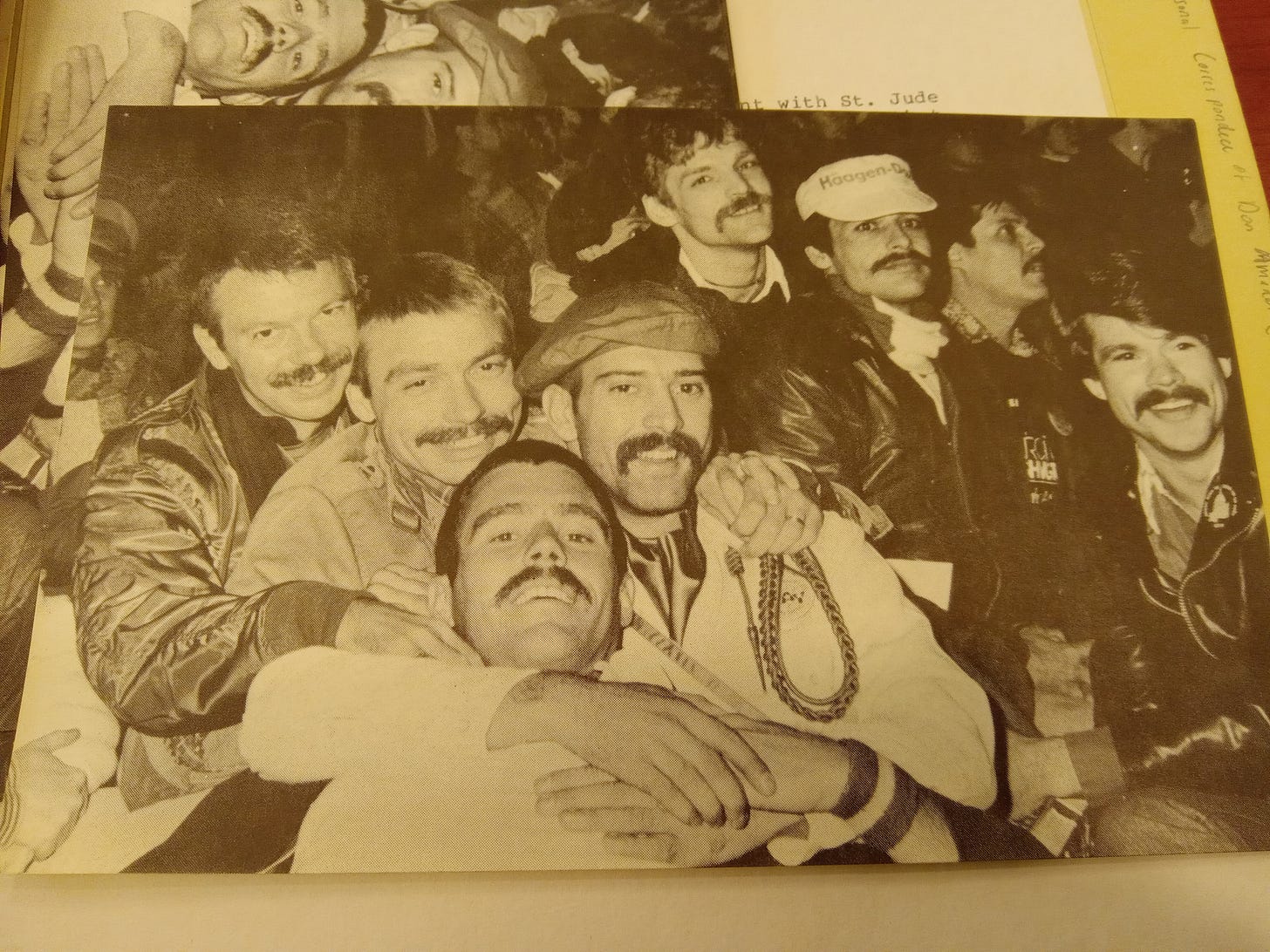

And he wasn’t no one, although you wouldn’t put him in the same league as friends of his like Harvey Milk and Cleve Jones (who before becoming the AIDS Quilt guy seemed placed, in say 80-81, to play the Jesse Jackson to Milk’s MLK—positioned as his successor notably by Randy Shilts, something I’ll post about as a future date)—besides running for office (the California State Assembly) in the late 70s (see poster below—I love any appeal of ‘This is ____ Country’), he was one of the first people to teach Gay Studies courses, in various schools around southern California.

This was a time when ____ Studies (Black, Chicano, Women’s—but I think at CUNY also Italian-American) were both taking off, in a complicated political context. There’s something apparently left-militant about the demand for X Studies, especially, say, if you’re a group of armed black students taking over building at Cornell (and as it were black-pilling Harold Bloom in the process), but then as now one might point out that demanding to make additions to curricula, however noisily or even violently you do it, is a demand to be included and even assimilated—a demand to be part of the system (which I don’t hold to be a bad thing, necessarily—the system is where it’s happening!).

And in the context of the 70s, making ‘ethnic’ demands (in the ways that gay and women’s movements were often framed as pseudo-ethnic ones) could easily seem downright conservative, with Nixon and Ford and many right-wing Rust Belt politicians promoting various sorts of white ethnic identity politics and the logic of the white-ethnic ‘neighborhood’—which could be deployed to resist busing (keep your kids in neighborhood schools) no less than swapping out of urban industrial zones for new white-collar downtown offices and playgrounds for proto-Yuppies (from whom the ethnic character of the neighborhood should be preserved). To position your group as deserving its own spaces (neighborhoods, schools, university departments and courses, etc) and symbolic resources—its own slice of national attention—can be done in a rhetoric of ‘solidarity’ with other groups or in one of competition with them, but in either case it seems in friction with calls to burn the whole thing down.

(The struggle to preserve the existence of your own group, to keep its consciousness of itself sharp and to maintain a physical territory and an archipelago of specific institutions for its population is not, I hate to have to stress, something essentially fascist or even illiberal—nor again a reliable means of attaining social justice—but is just what politics and culture is—and it can be, should be, I hope, a fairly gentle exercise of jockeying over space on the syllabus and the biggest float in the parade, not more intense and dangerous than our own everyday individual attempts to secure our place in the sun of other’s esteem)

Harvey Milk, notably (at least as Shilts tells it in his just-before-AIDS bio The Mayor of Castro Street), used a discourse of ‘neighborhood’ politics (and his status as a small business owner—of that camera shop) to link San Francisco’s various white ethnics, including conservative Italians, to blacks, Chinese and gays as having socio-economic common interests that set them against the Democratic establishment’s plans for turning SF into, well, what it became—a bunch of skyscrapers and bougie treat shops for knowledge workers.

People on the left and right—whether self-hating Marxist gays or homophobes with some college education—love to blame gays for gentrification, for being agents of capital, childless hedonists carrying out a worldwide program of cultural homogenization (globohomo)—but, critically, if gays were and are the people fixing up the brownstones of New York and Victorians of San Francisco (which I have to say don’t strike me as a crime quite up there with the Middle Passage and the Trail of Tears), they were also occupying—like ‘ethnics’ of the 70s more generally—an odd political position that wasn’t quite right or left, combining discourses about protecting 'neighborhood character’ from outsiders and city/state/federal planners with a desire to, well, make their neighborhoods nicer… complaining about police harassment while also wanting more police protection… wanting to join the political establishment and suspecting that anyone who did is a sell-out… all the sort of very normal contradictions of middle-class people who, for whatever reason, aren’t leaving the city.

All that to say ‘identity politics’, in every instance, isn’t a determinate entity we can know in advance to be ‘left’ or ‘right,’ ‘assimilationist’ or ‘radical,’ or can understand without investigation to be a distraction from or means of working out the ‘real,’ ‘material,’ ‘economic’ issues facing people—we have to ask what people are doing with claims about identity, what kind of coalitions and alliances they are building, to what ends, etc etc… at least if we don’t want to be retarded about it.

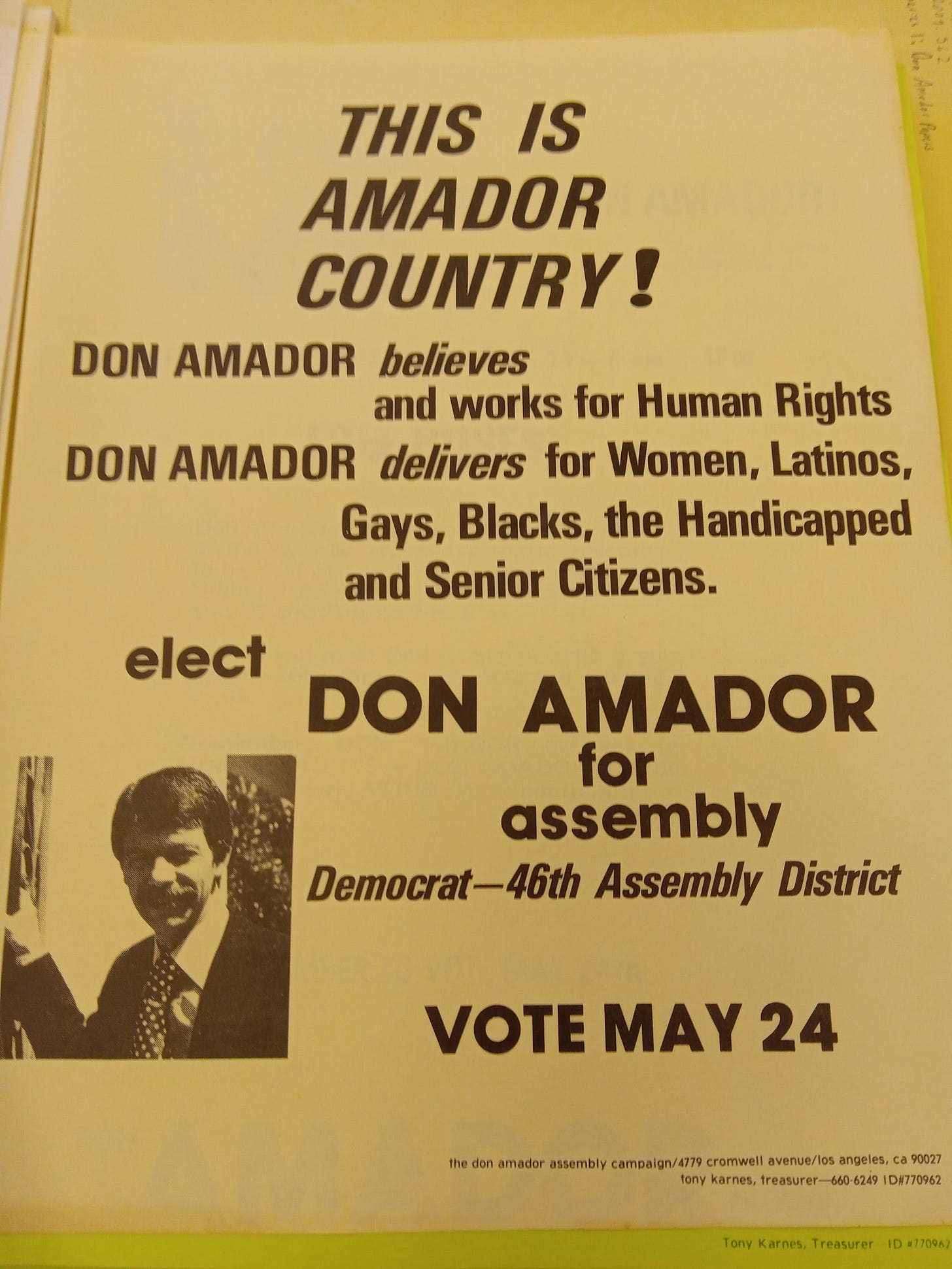

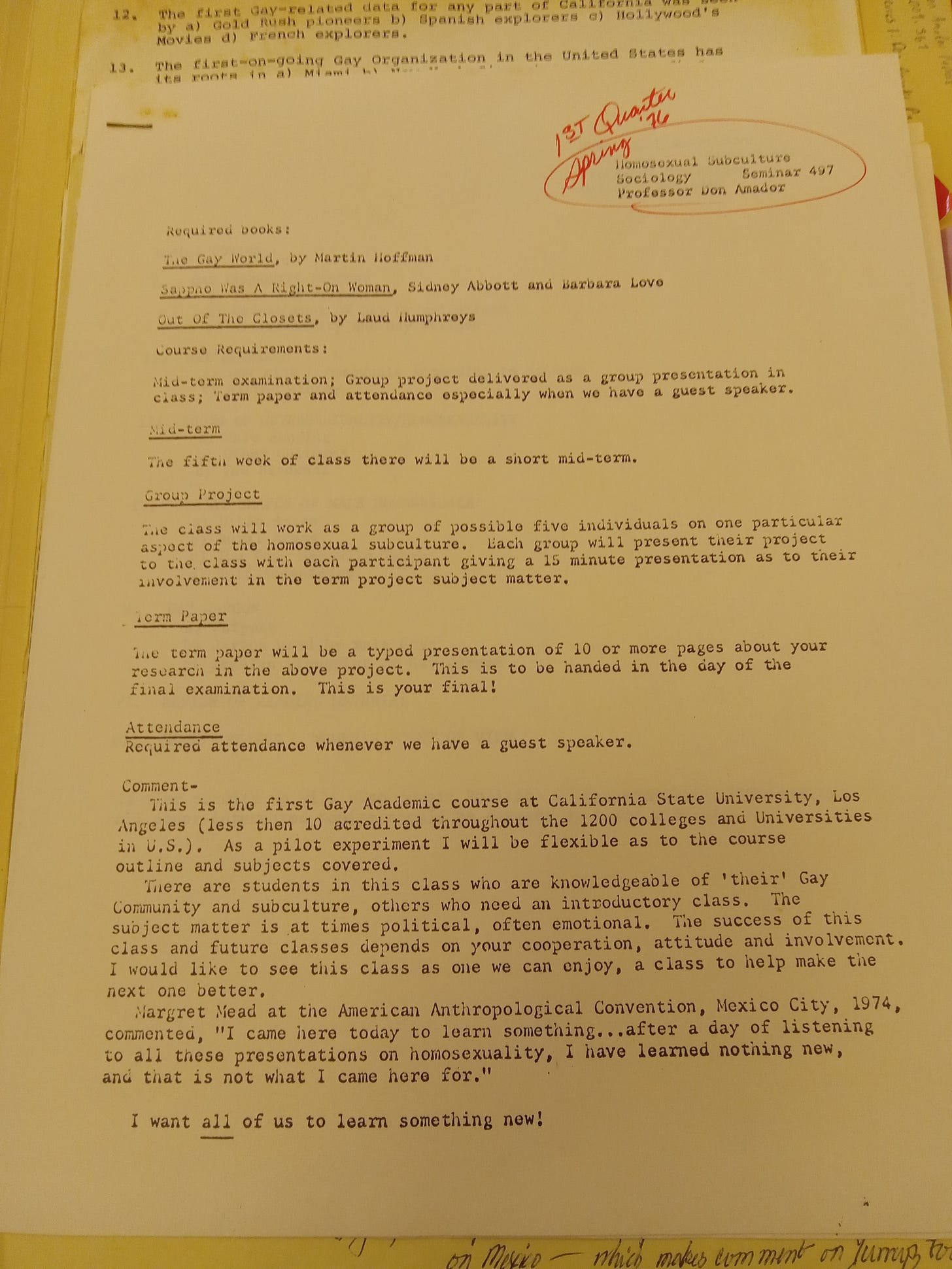

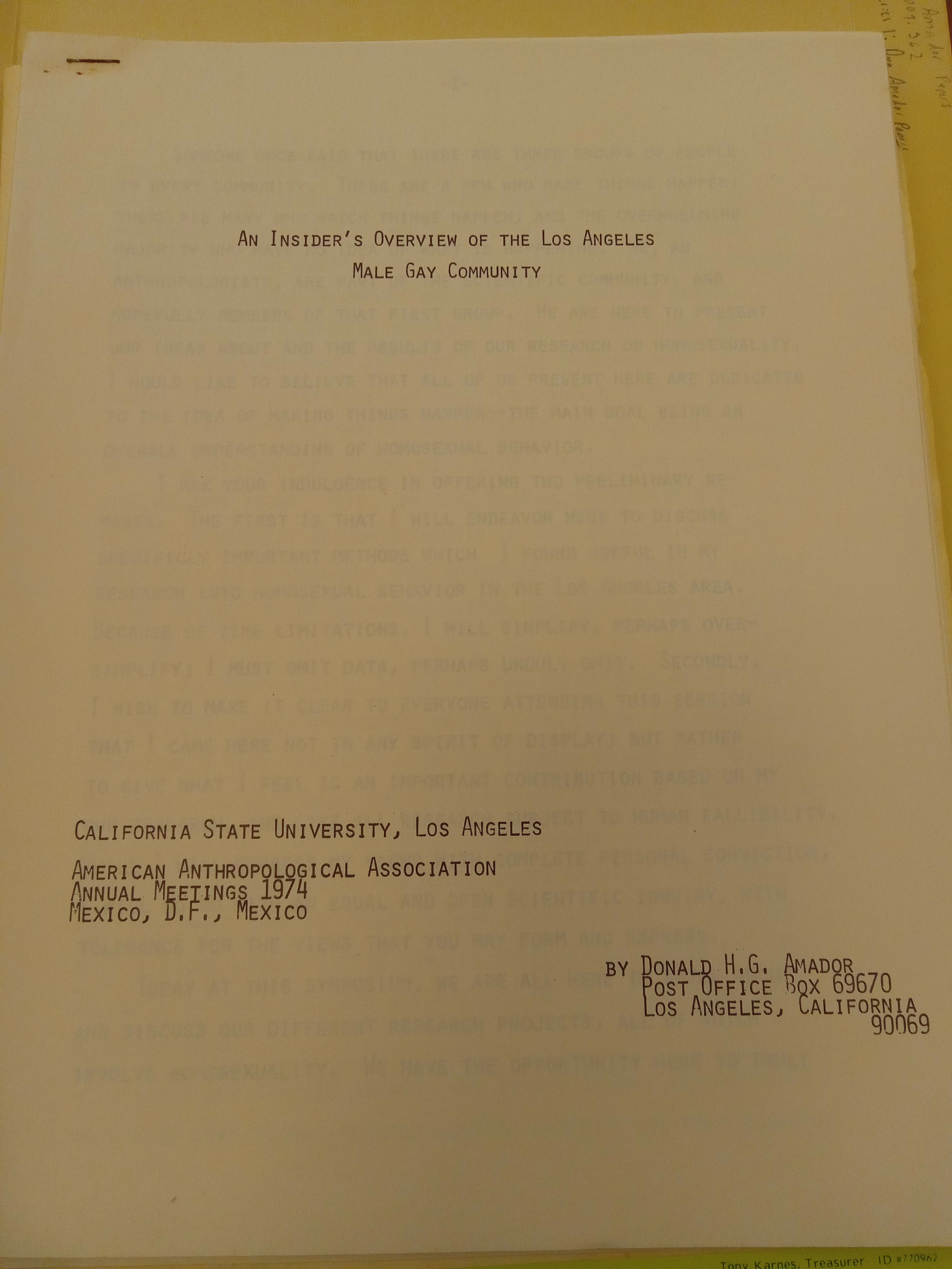

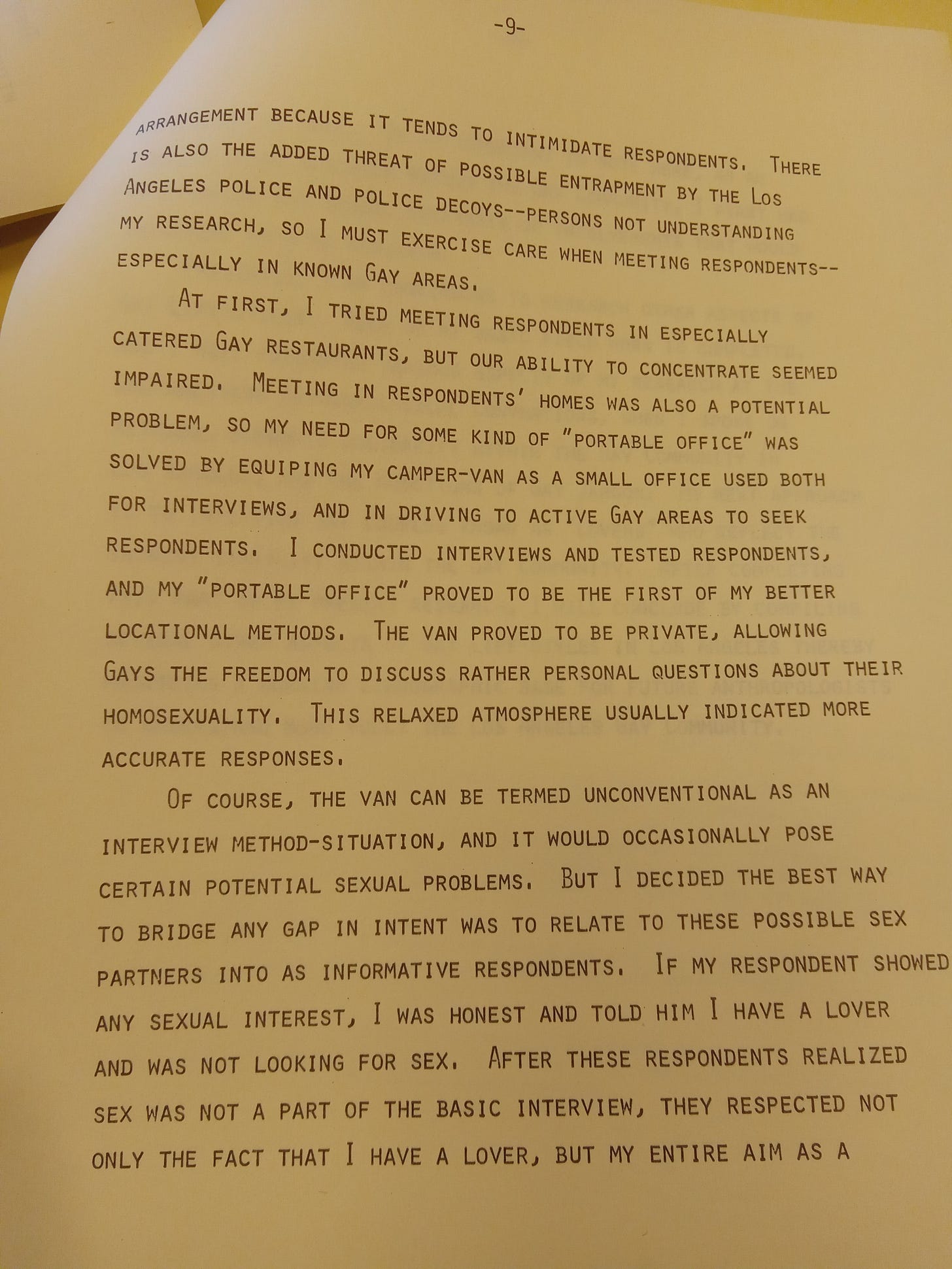

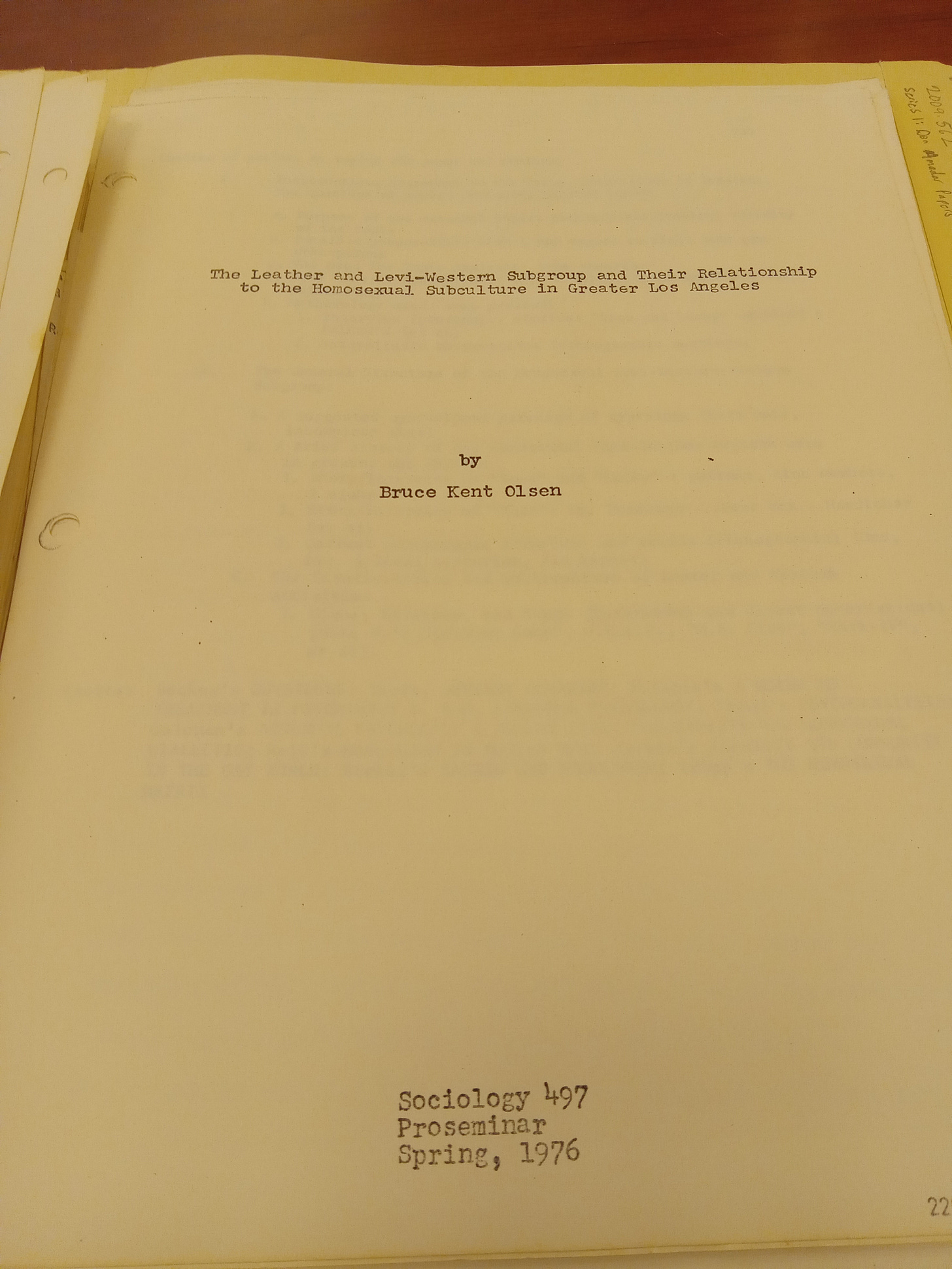

Anyway—back to Amador, who for being a founder of Gay Studies (a discipline that now doesn’t really exist) wasn’t quite an academic. After some time in the navy, he got a masters in anthropology studying LA’s gay community, which he wrote a thesis and then conference papers on, parlaying that into a series of teaching positions at a number of area schools (but wasn’t able to get into a PhD program—he applied, for example, to Indiana, hoping to work at the Kinsey Institute):

research isn’t always easy…

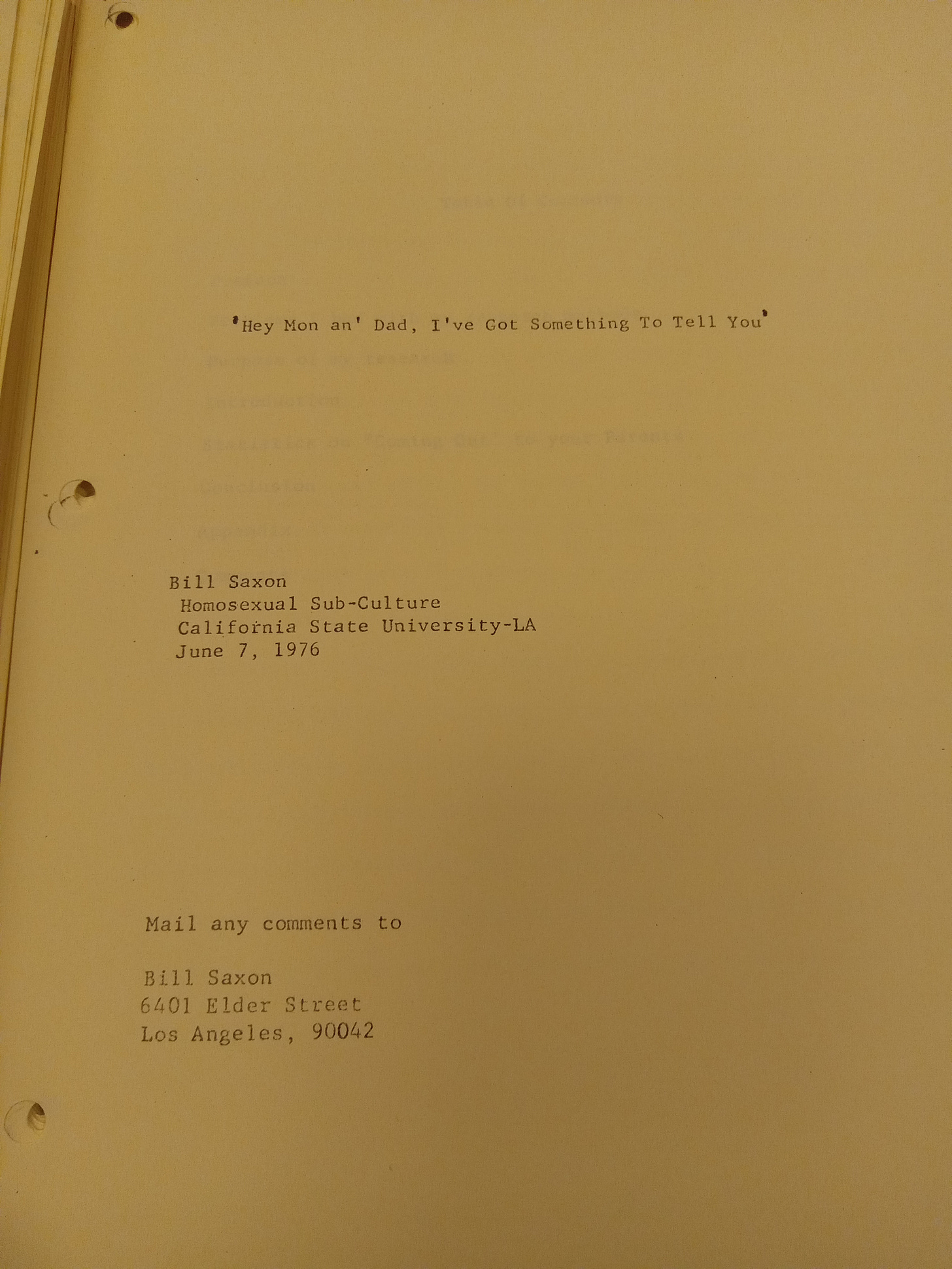

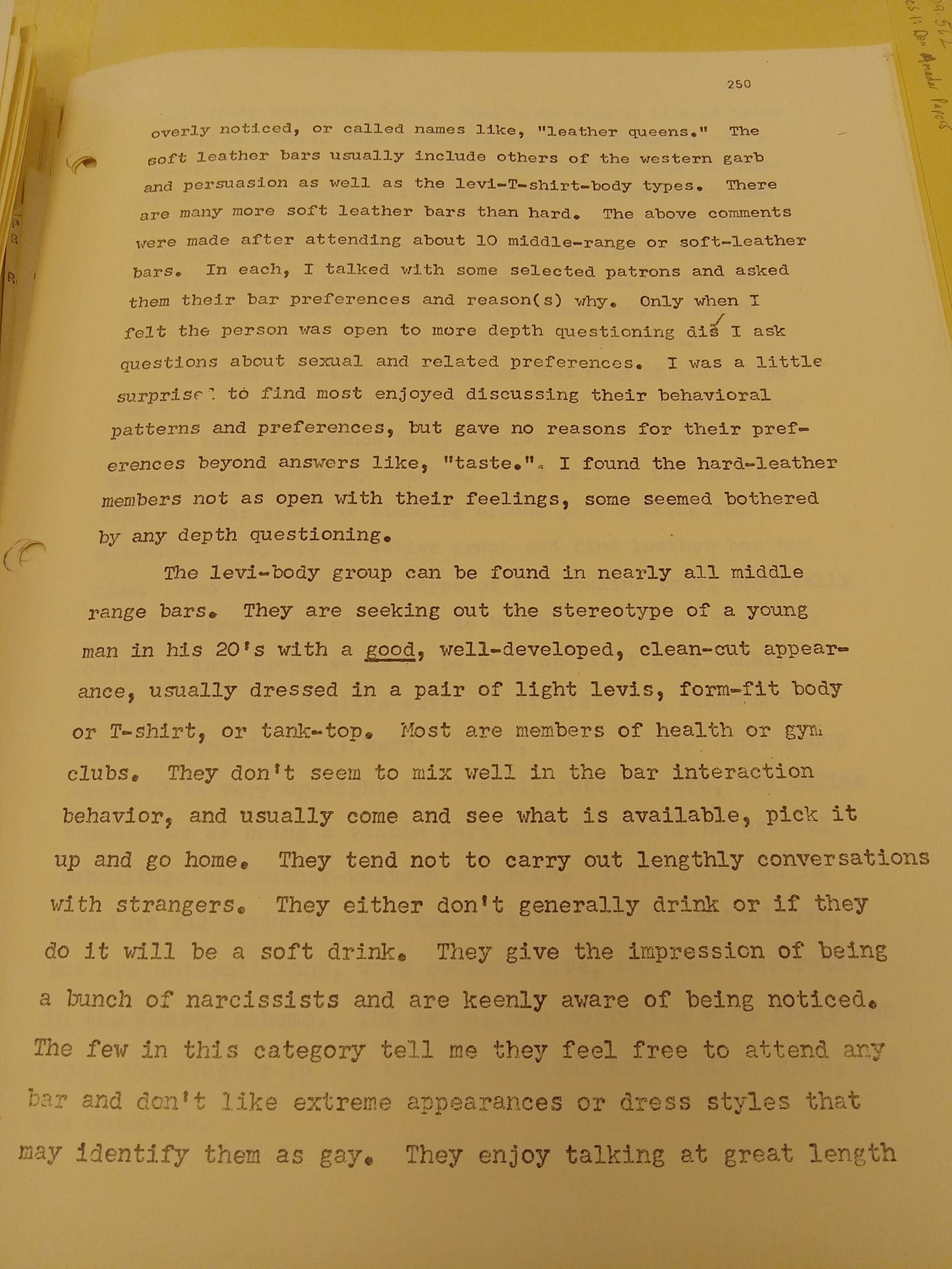

Amador’s studies consisted of interviews, surveys, etc, which offer a somewhat interesting but not very theorized or really surprising look at the LA scene (the period just before this is well-covered in the monograph Pre-Gay LA)—what’s mainly important I suppose is his courage in being ‘out’ in a precarious academic position, and then creating courses that he meant to be a platform for further research. While some of the content was the ‘Famous Gay Historical Figures’ collective self-esteem-boosting since familiar from every Pride month propaganda (and even this shouldn’t be discounted, it was novel and important at the time), what’s most exciting, for me anyway, about his courses was that he had his students go write papers based on their own research/experience on various aspects of local gay life:

I wasn’t able to find out more about Bill (William?) Saxon unfortunately—as always reading stuff about young gays from this era, I feel nauseated thinking about all the awfulness behind and ahead of him then, and wish I knew he made it out all right…

Although maybe “Bill Saxon” is a pseudonym, since I can’t believe “Dakota Sands” is a real name:

There were a number of papers about fetishes, in fact:

I hope these kids made it and are happy thriving Eldergays somewhere today…

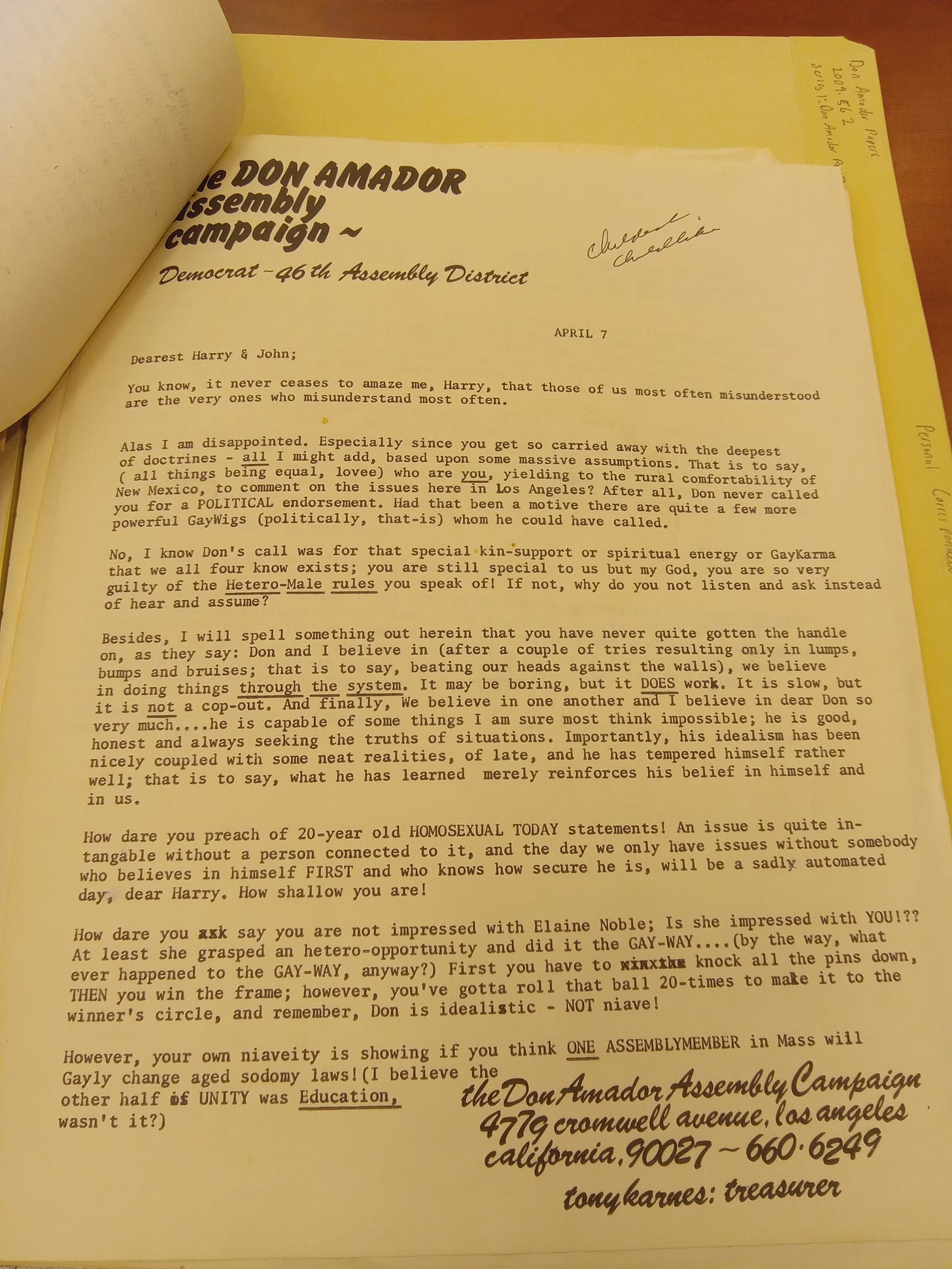

Finally, I haven’t researched Amador’s run for office in 1977, but it gave rise to a funny exchange with Harry Hay (who called him Dinah—they used campy female names to write to each other), the radical faerie communist who denounced him for pursuing anything as hetero as electoral politics:

and the response, from Amador’s partner Tony Kerns, in full ‘don’t you talk about my man’ mode:

Oh Barbara,

It’s so fun to read about our lost history. Cattiness sans cynicism is your groove. May today’s gayborhoods follow suit. Thanks much!

Yours, Gigi