Michael Denneny published some of the most important and controversial books of the AIDS crisis—such as Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On and Larry Kramer’s Reports from the Holocaust. He also published some of the most beautiful fiction, like Allen Barnett’s The Body and Its Dangers and Mark Merlis’ wise and gorgeous An Arrow’s Flight.

He thought about what he was doing as “Arendtian praxis,” he told me in an email shortly before his death in 2023. I’ve been trying throughout the posts over the past several weeks to show how his engagement with Arendt and the thinkers she drew him towards shaped his vision of gay life and politics as grounded in aesthetics and the exchange of judgments of taste, and I hope it’s become clear what that means.

I’ve expressed in my comments on his 1981 Manifesto how I think Arendt’s ideas, for all their power and utility, set him up quite poorly to think about how gay politics, like any politics, would have to include making material demands and couldn’t just be a matter of securing symbolic goods like representation. But even within that framework, whatever its limitations, Denneny did a lot of amazing work during the AIDS crisis, and understood what he was doing in terms consistent with his dissertation and writings on Arendt in the 70s.

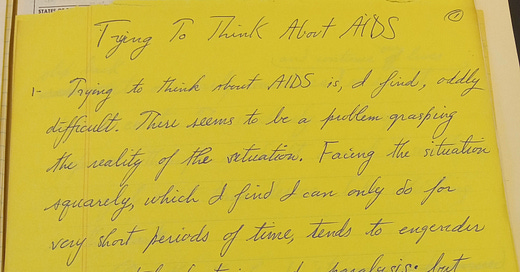

First, in an undated note, I think from the 80s, Denneny laments that he can’t seem to even think about AIDS; it’s too horrible.

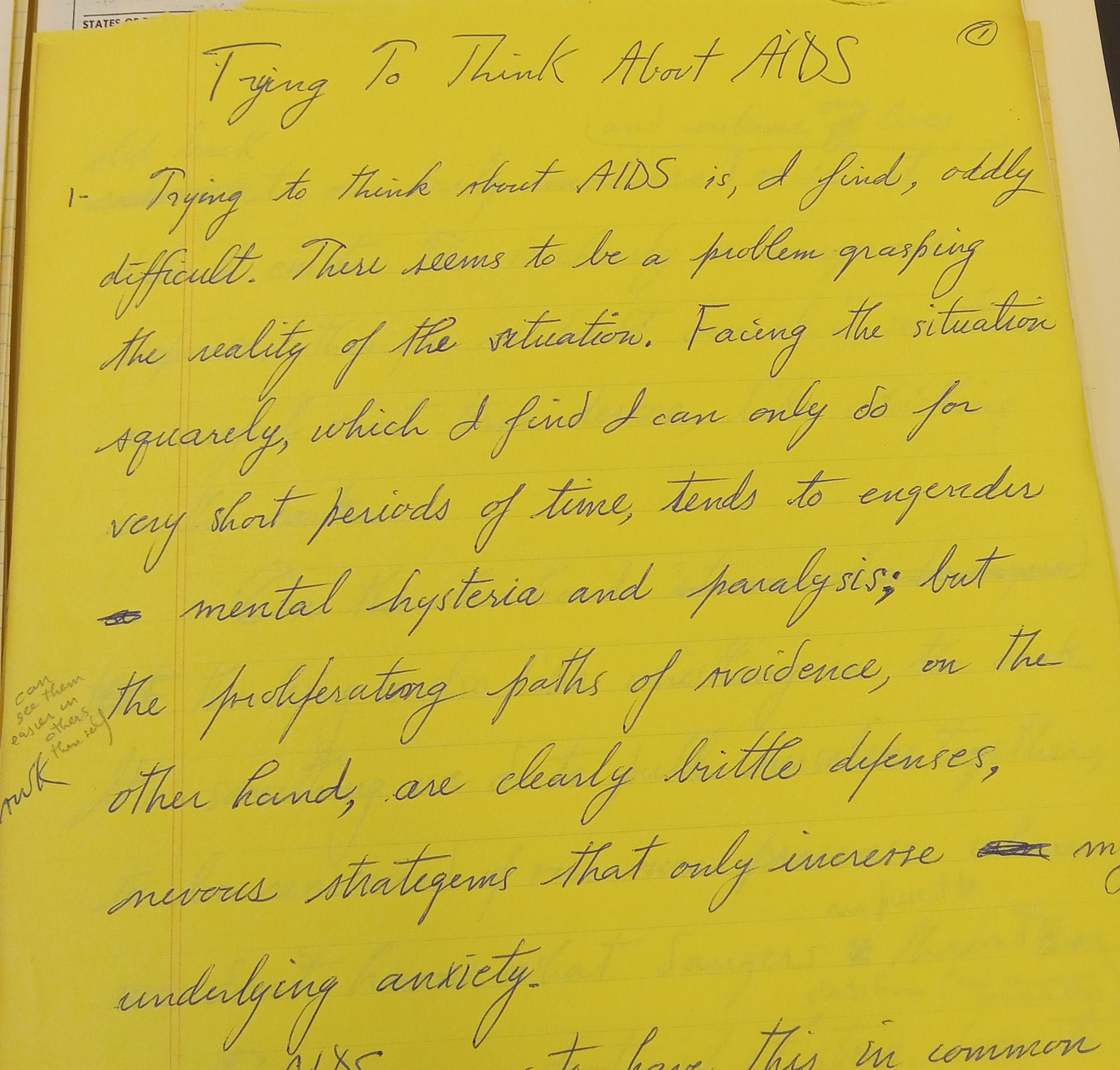

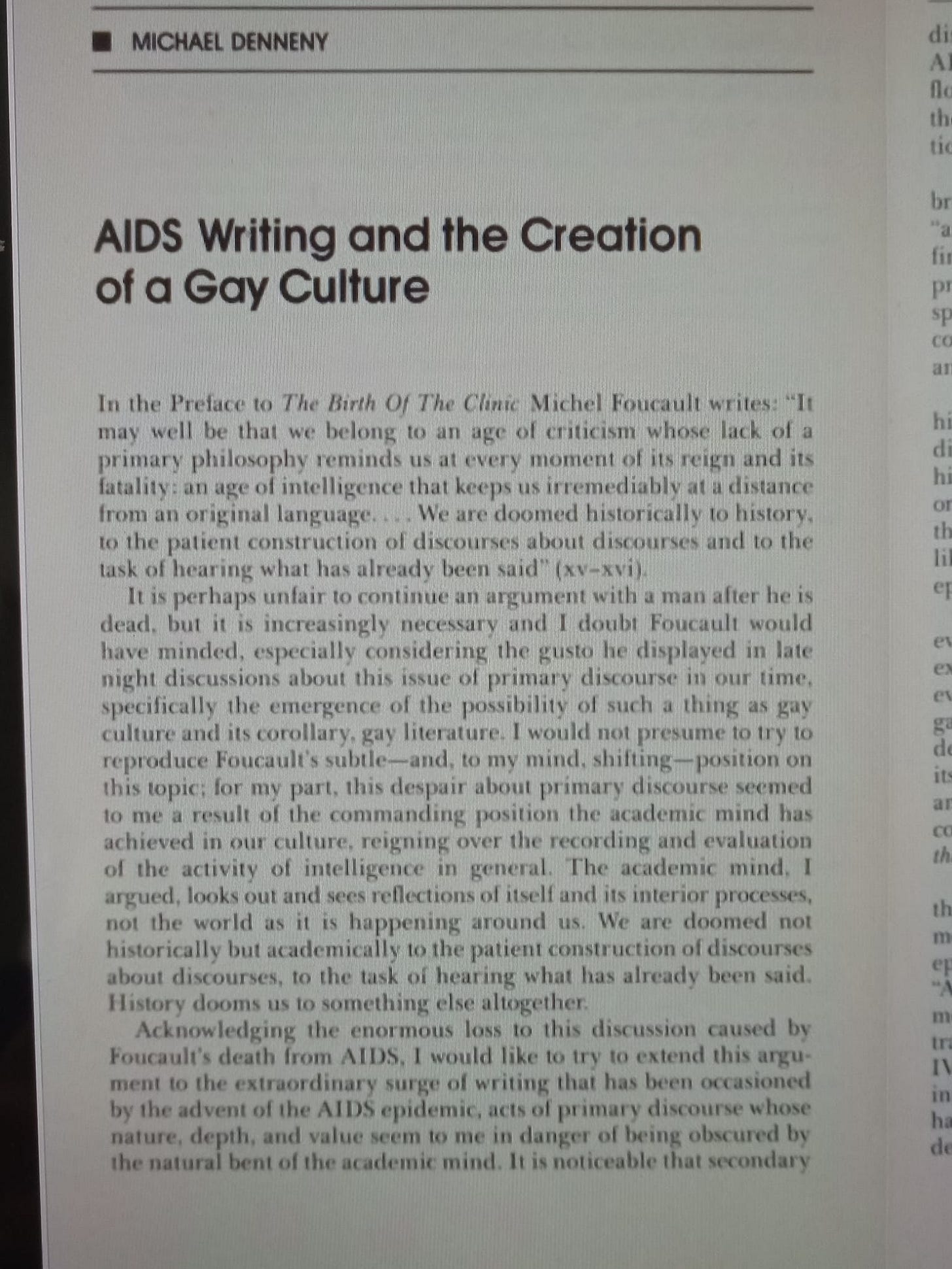

Of course he did keep thinking and writing about it. In 1993, during the worst of the crisis, he published an essay on AIDS and gay literature/culture that you can read in full here. He begins by taking up a challenge to/from/with his friend Michel Foucault, and then quoting from Arendt’s translation of Sophocles that had ended his 1979 essay on her theory of judgment.

Denneny, like Foucault, is concerned with whether we (human beings but especially homos) can escape the modern discursive systems that have formed around us what Leo Strauss called a cave below the cave—whether we can emerge out of their categorizations into an open freedom, or whether we’re condemned to labor within them, forever merely commenting on the way our we have been labeled and named (for me on these points, see my engagement with The Birth of the Clinic and Foucault-Strauss parallels). Denneny calls such an emergence a passage from secondary to primary discourse—or in his 1981 manifesto, a move from being homosexual (a medical-legal categorization invented by straight experts) to being gay (our word, the meaning of which remains ours to invent).

Being gay means being part of a self-creating cultural world, and the point or rather the glory of such a world is to be able to maintain a space of appearing in which human beings can show themselves and express their judgments to each other—most gravely, their judgments of outrage and horror in the face of catastrophe that threatens the world’s survival. We are vulnerable, mortal beings, and the world we hold together in discourse is also fated to perish, but within it we can, while we hold and are held in it, show who we are as we show what we do and say what we think.

Denneny rarely addressed his own life in interviews and other writings; in a 1998 interview with Art and Understanding, a magazine for people with HIV/AIDS, he talked about being in the hospital with an ex-lover, dying and severely demented, and about the many authors he published—Randy Shilts, Paul Monette, Allen Barnett (who you have to read)—who had died.

It’s jarring to see him talking about these deaths, while also bragging about his good head for business, much less making the astonishing claim that out of AIDS literature gays are in the middle of an extraordinary Renaissance. Denneny had made claims like this back in the 80s too and was criticized for it by people like Douglas Crimp. It does make me uncomfortable, even at this distance in time, so I can only imagine how it might have upset people then. But from within the perspective that Denneny took up from Arendt, it’s a legitimate, humane, even noble idea—that one of the highest exercises of the human spirit is to keep bearing witness in the face of catastrophe—and that AIDS literature is as glorious and beautiful as Homer’s witness to the Trojan War.

In fact, the best novel Denneny ever published (perhaps the best gay novel, as good or better than Dancer from the Dance) came out that same year, and has exactly this comparison for its theme. Nothing I could say in an essay about the way Denneny’s sense of gay writers meeting the challenge of AIDS connects back to his earlier writing on Homer and the aesthetic life would be able to match what Mark Merlis does in An Arrow’s Flight.

Lest we forget, Pyrrhus lives deep inside us all. Thanks for keeping him there.