The poet, novelist, editor, etc-etc Charles Henri Ford was born in Brookhaven, Mississippi, a place familiar to me from childhood trips as the last proper place before we got to the nameless dirt roads leading to my father’s parents’ farm. So out of upbringings even more backwardly provincial than mine sensitive, pretentious gay boys have been springing, in CHF’s case upwards into transatlantic modernism, in mine for the moment as far as Pasadena.

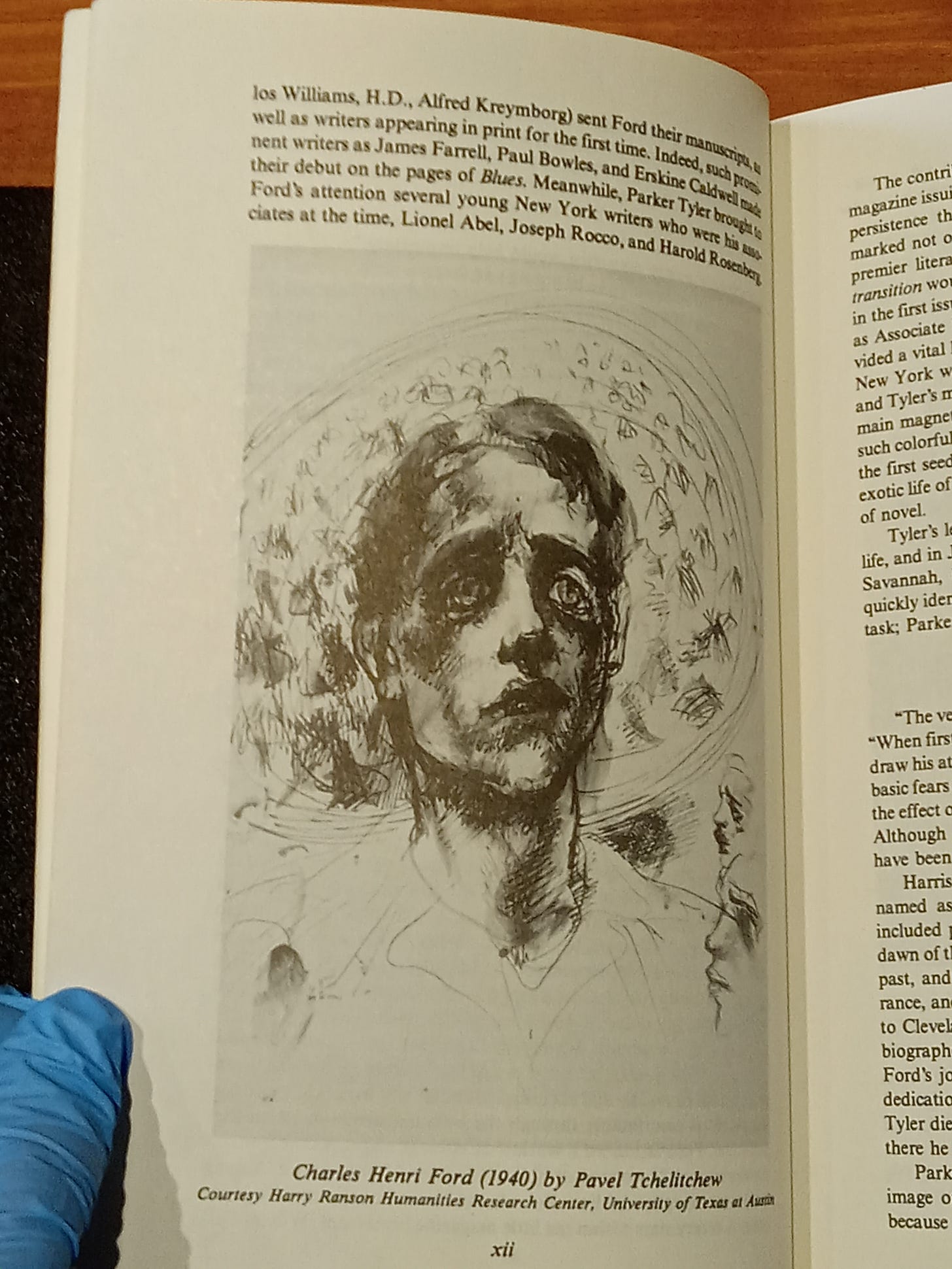

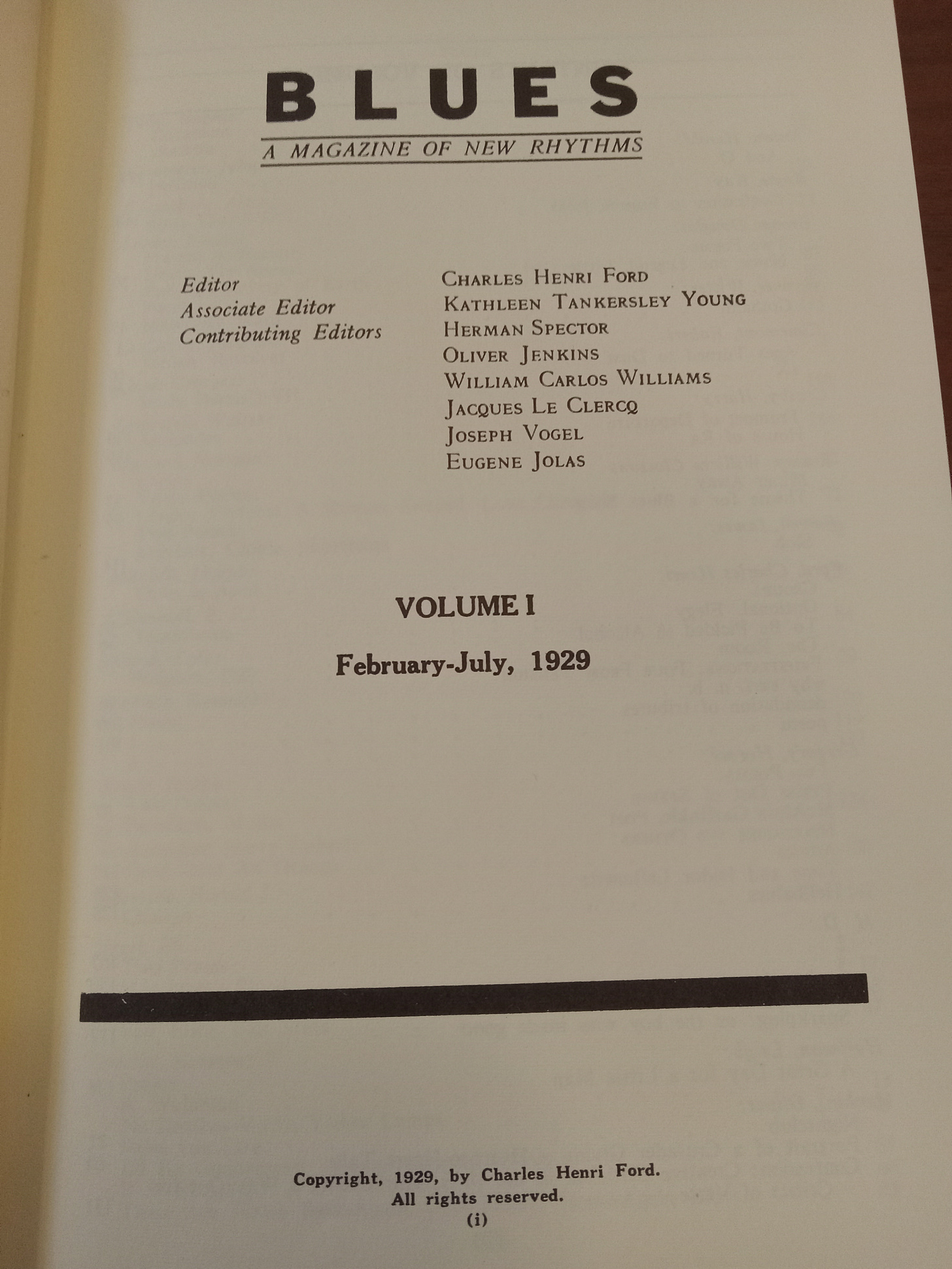

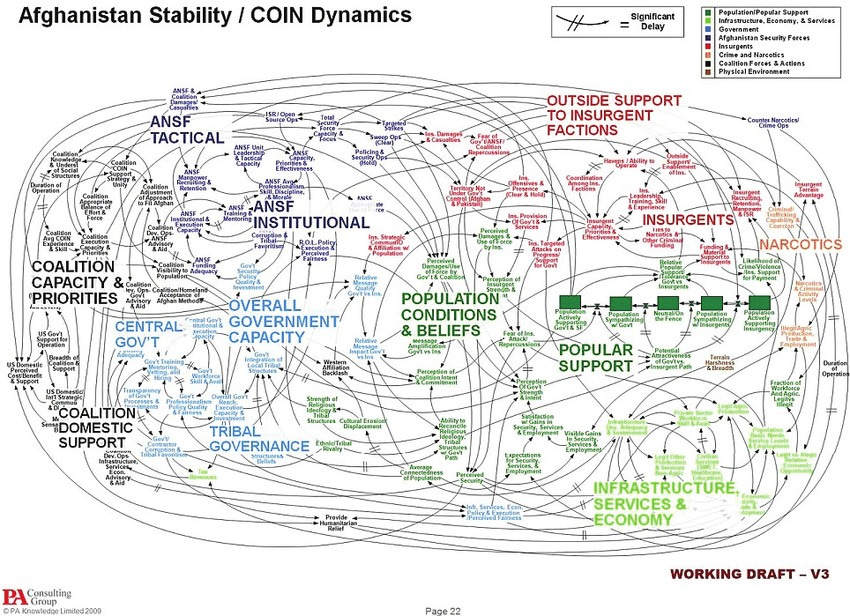

Ford co-founded the influential little magazines Blues and View, which had a big role in bringing European surrealism to America and promoting a second, post-Eliotic generation of avant-garde poetry. He wrote with one of his co-editors, Parker Tyler, the novel The Young and the Evil, which is sort of the gay male Nightwood. Like Tyler (who gave us the enormous and terrible and rather justly forgotten but then again please do remember it gay modernist epic poem The Granite Butterfly), he was also a poet in his own right, and a bad one. He was also, finally, the lover and collaborator of the artist Pavel Tchelitchew, who illustrated a number of the books he wrote and edited.

Although they didn’t get much picked up by the post-Stonewall gays, for reasons that may become clear, Ford and Tyler did have an oblique contribution to the Christopher Street scene by way of promoting the early work of Michael Denneny’s mentor Harold Rosenberg—who although straight and in some of his art criticism rather hostile to what he saw as the gay mafia had been in his youthful career as a writer encouraged by Blues and View.

Ok enough Encylcopedia Fagtanica. If there’s one thing I hate (and of course there’s a lot more than one) it’s the idea of writing to educate—I didn’t even like educating back when I was getting paid to teach (“What does ____ mean? —Well, gosh, Student, what do you think it means?” “What do you think about ____? [a question John Pistelli, God bless, is always for some reason entertaining on his Tumblr]—Well, as Whitney Houston once said…."). I had lunch a year or so ago with the gay critic Daniel Mendelsohn who a propos of something, I guess, said that he saw his task in his essays at the NYRB and elsewhere as the education of the public. Which to me sounds awful.

First of all, you readers have Wikipedia same as me; look it up (are we still, in 2025, saying “it’s not my job to educate you”? can I take that one back from the wokes? In my earliest writing for public venues in like 2020 or so I’d overexplain shit like “John Milton, the seventeenth-century poet,” but those annotated days are over—experience the shame and discomfort of ignorance; amend your lives!).

Second, I don’t know, I’m thinking. I want to share an enthusiasm and a promising uncertainty, not a bunch of facts set in a balanced, comprehensive provisionally final perspective. I’m not of course taking up a position exactly of humility in my writing, but I don’t want to play teacher, as if writing were the dead-end of learning, rather than only one of the moments of my protecting my precious right to remain unsure of myself. There seems something terribly presumptuous both in the writer supposing he can educate the reader (I know, you don’t) and the reader expecting to be educated (as Ms. Valentina Bartleby once said, ‘I’d prefer not to serve’).

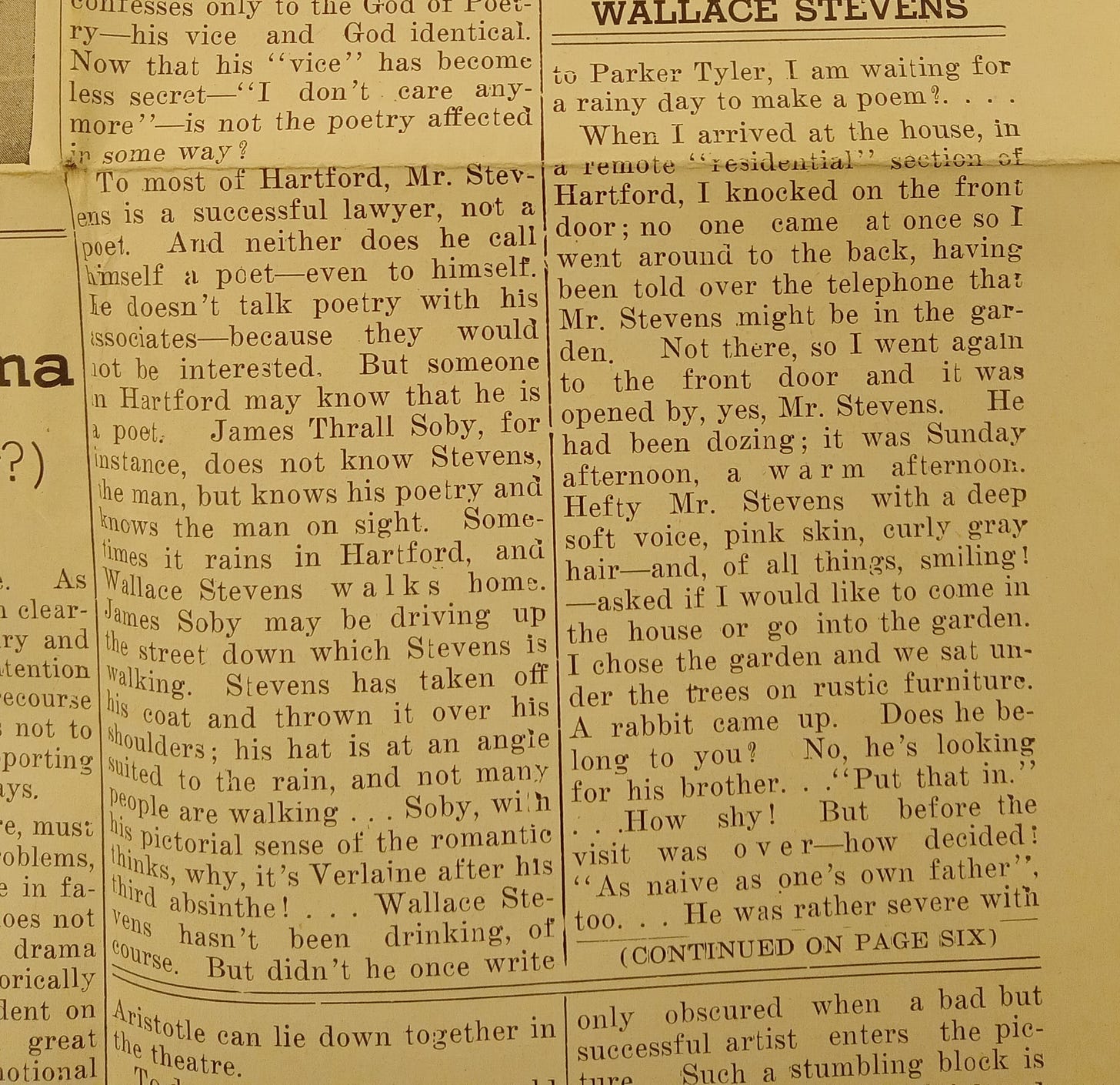

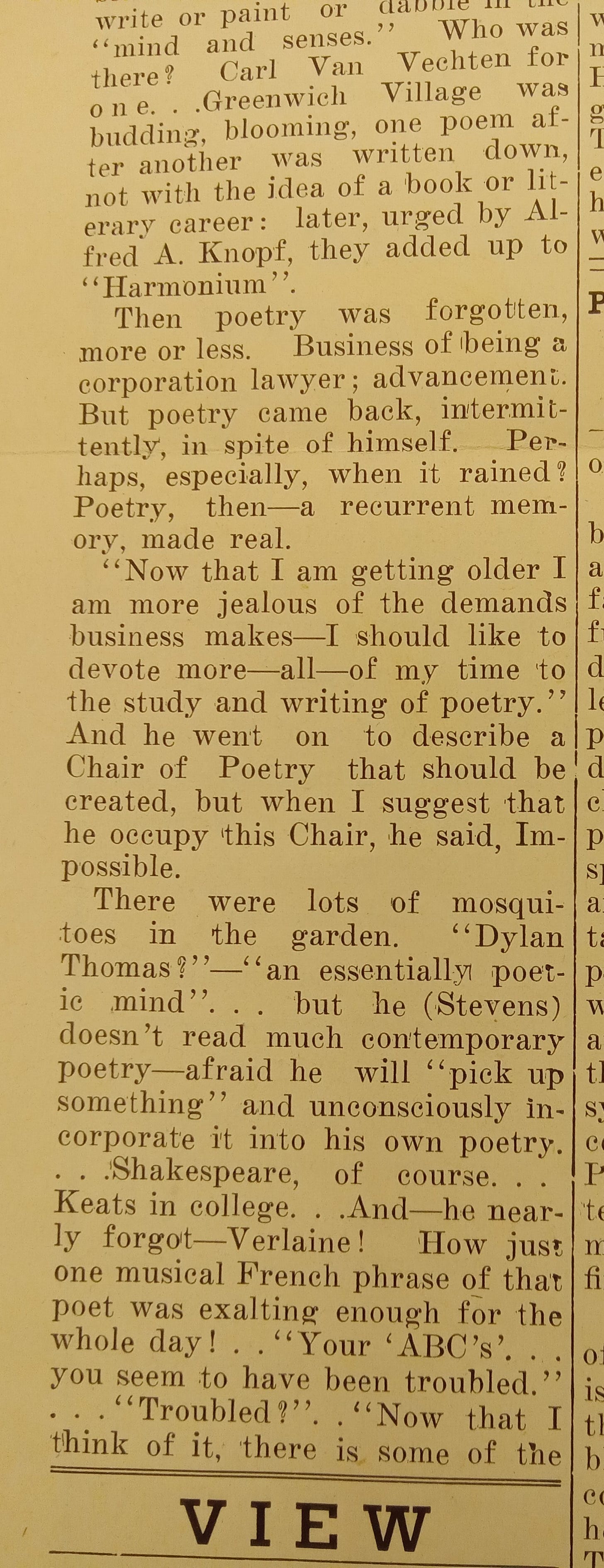

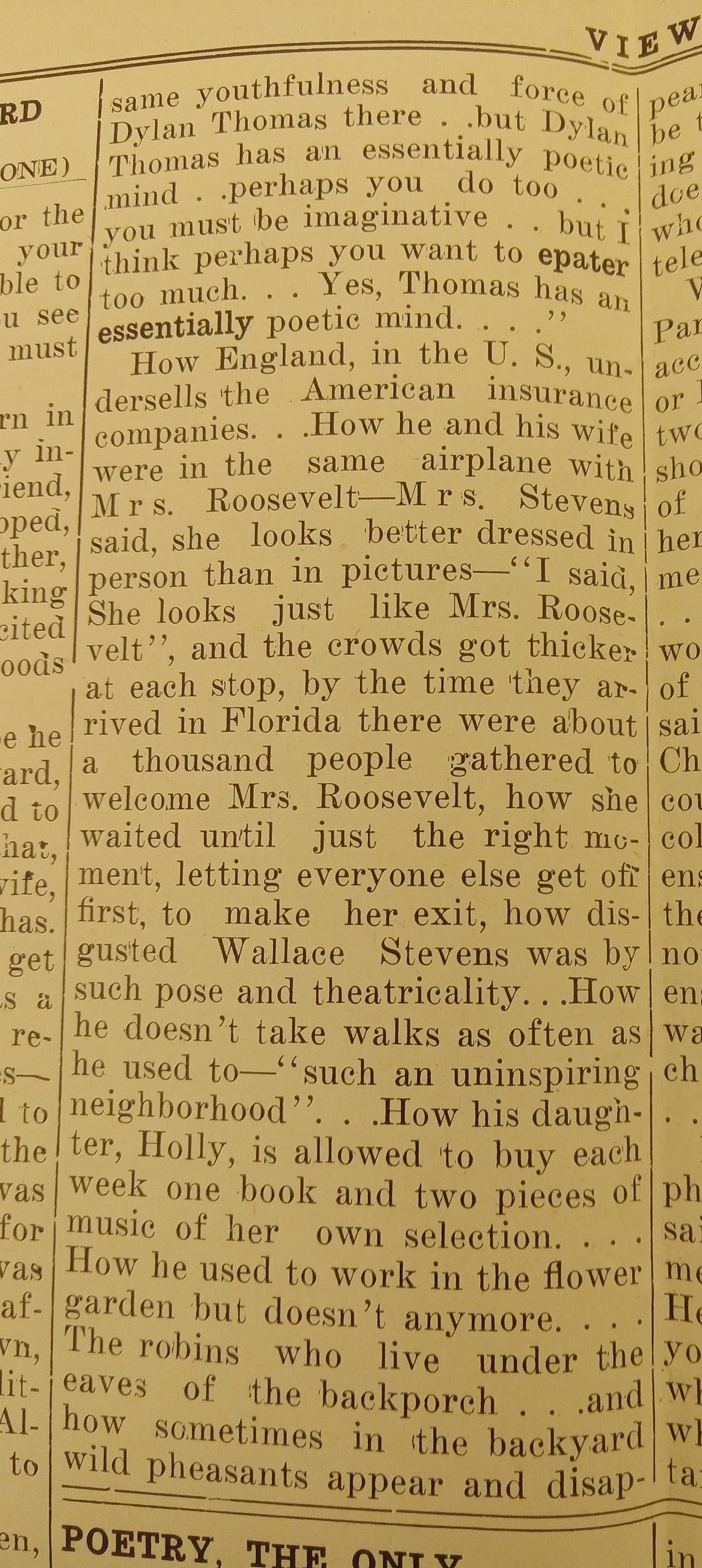

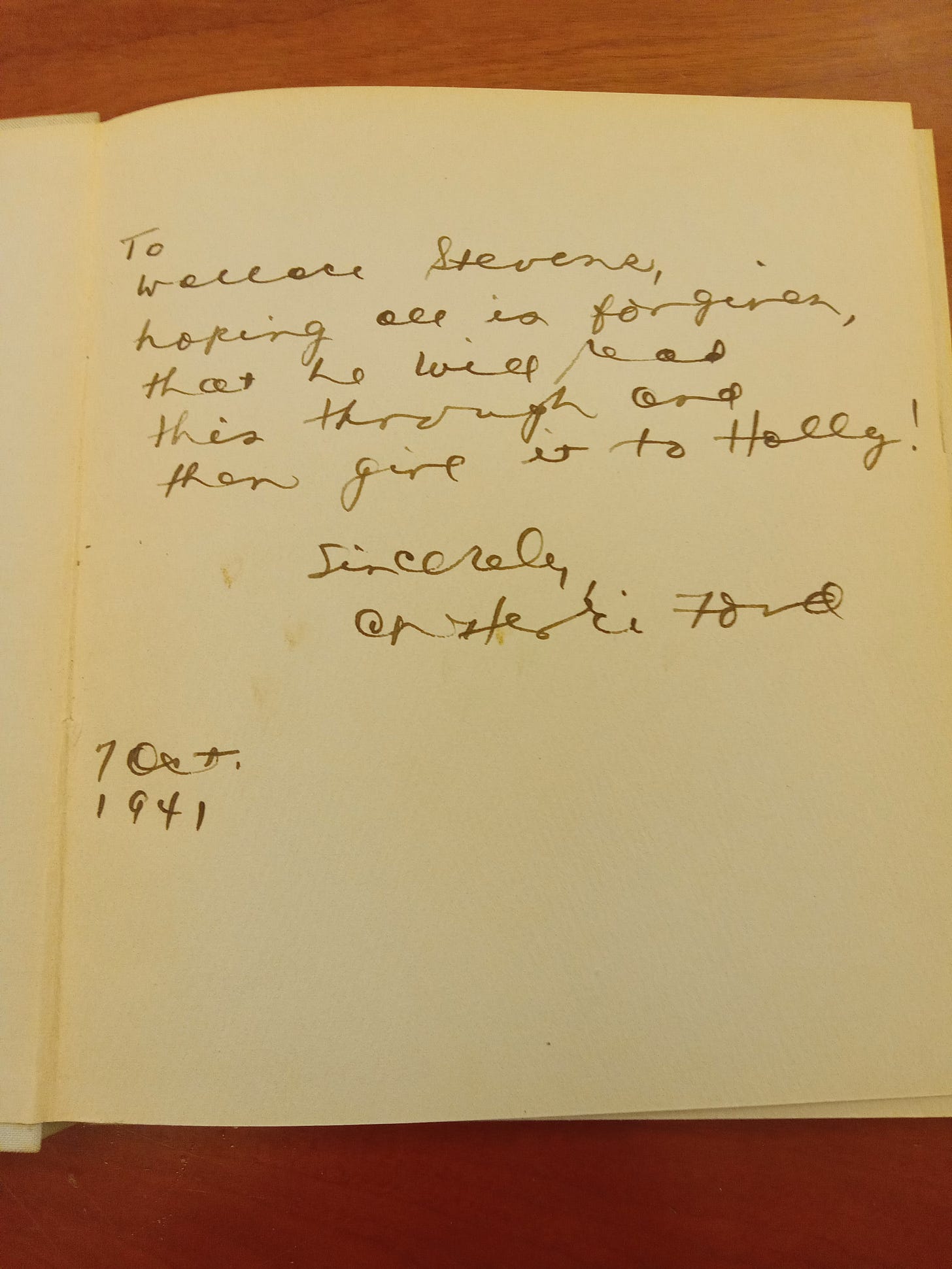

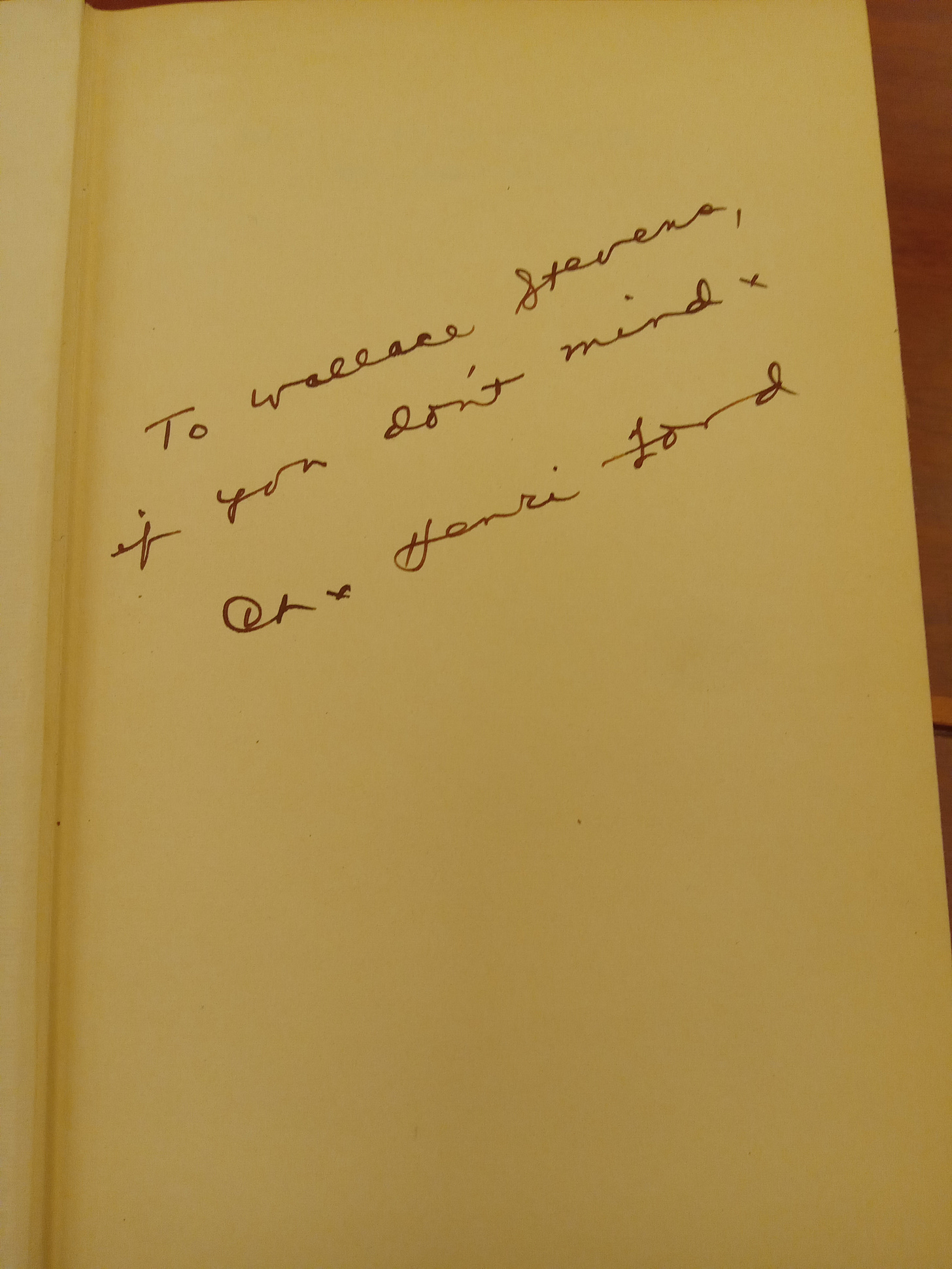

But back to Ford! For some reason the Huntington has Wallace Stevens’ library, which includes a number of books Ford sent to a man he called in View “the Verlaine of Hartford” (is Wallace Stevens, like Frasier Crane and Roger Ebert [for his service to the community in writing Beyond the Valley of the Dolls], an honorary queen?):

I find this intolerably cutesy, but I appreciate Stevens (whose ‘Materia Poetica’ appeared in the same issue of View) getting some digs in at the expense of CHF’s poetry, which is, as we’ll see, quite bad, and bad in a way that reminds us how it is to write good Stevens, who makes being himself look so easy (gays still haven’t learned how hard it is to write good O’Hara, either).

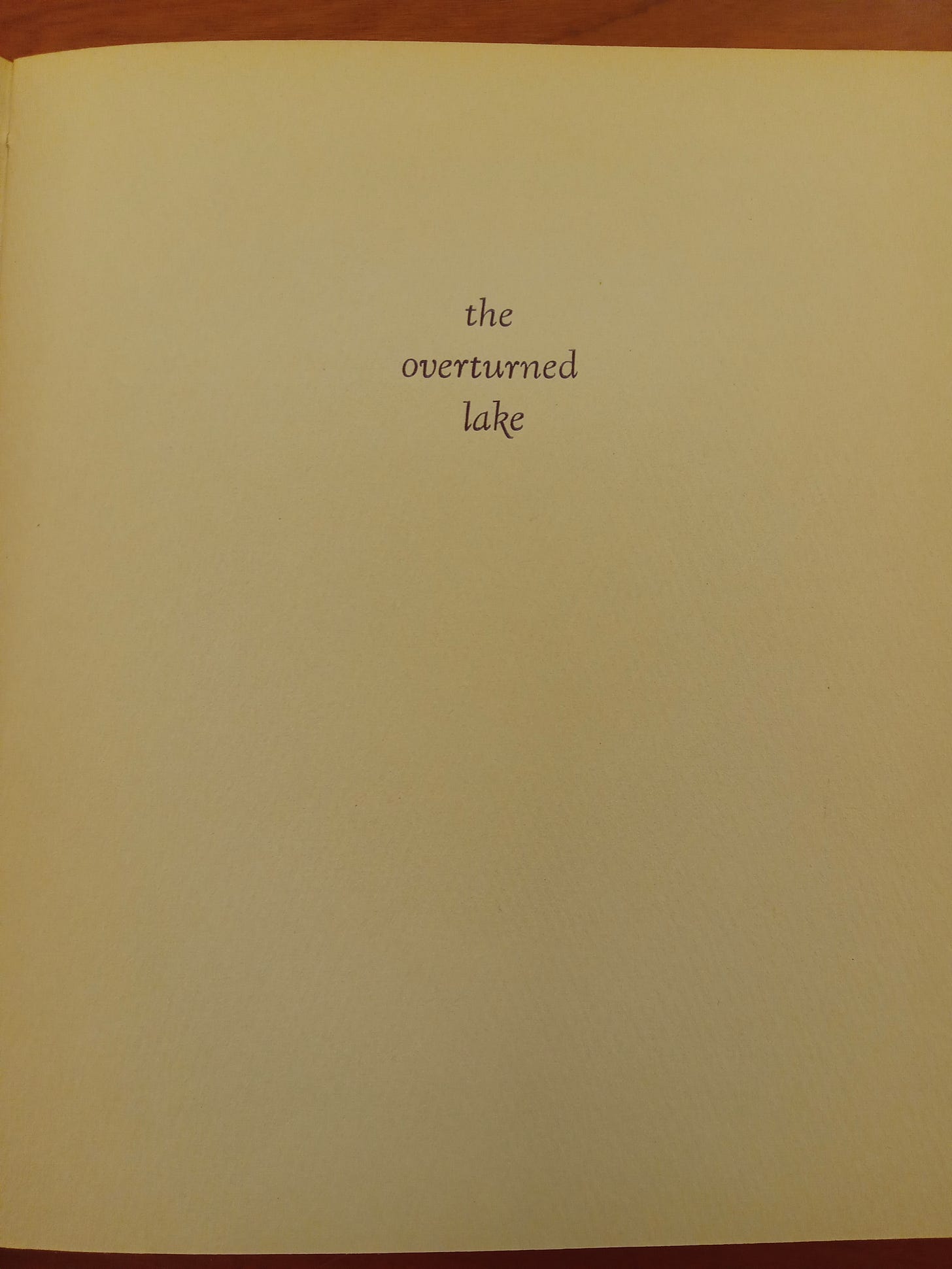

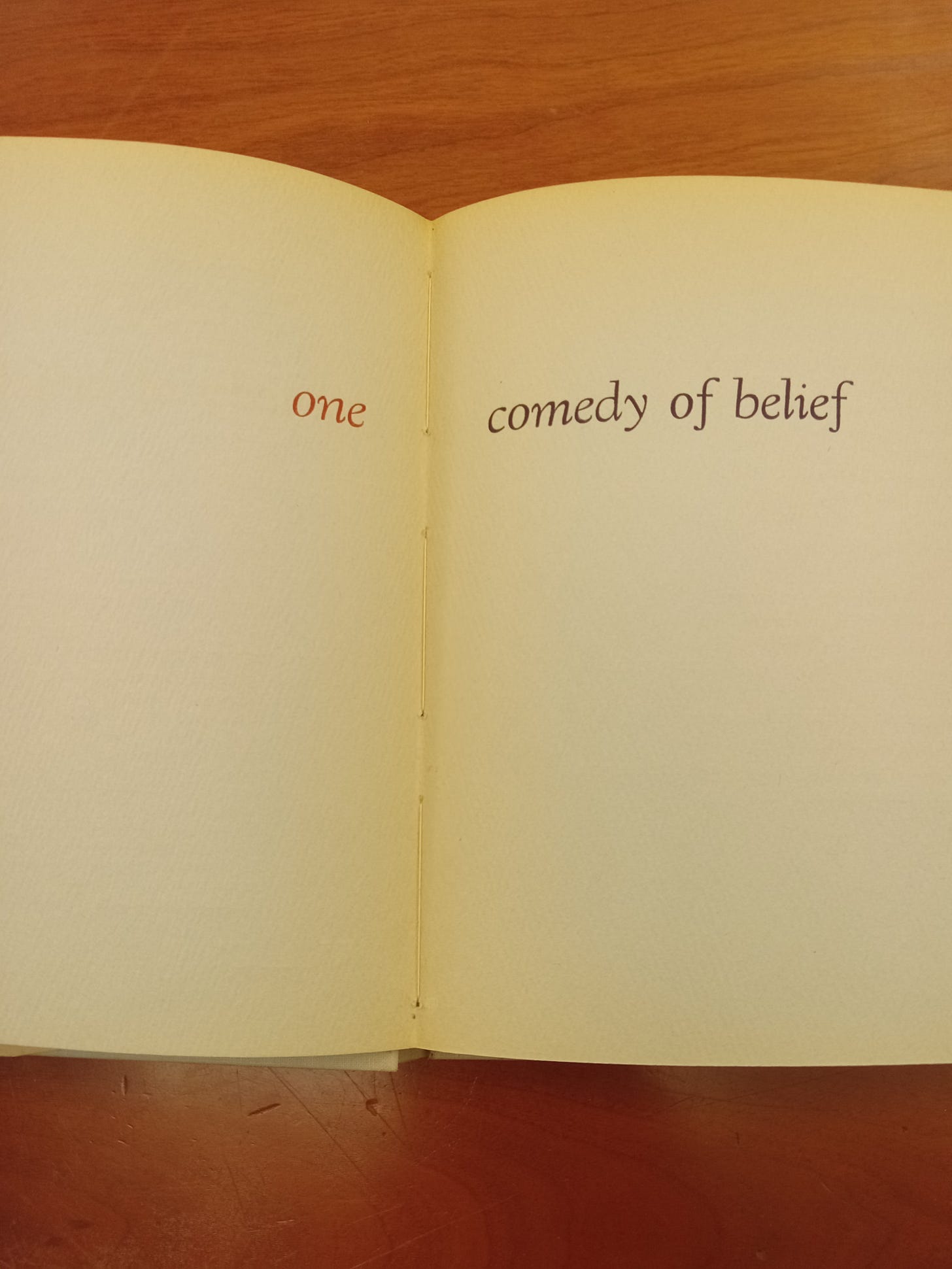

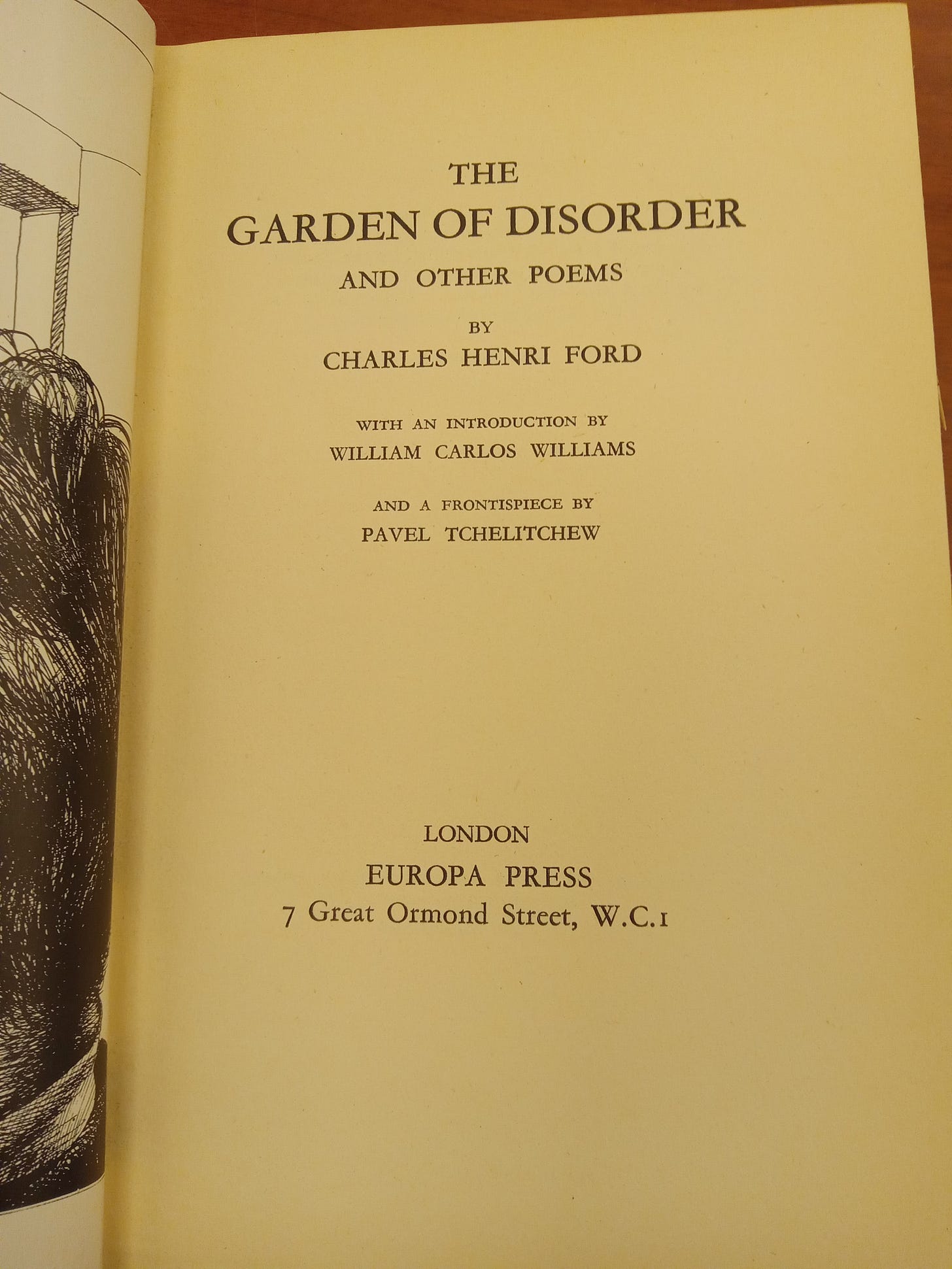

For example, this book of poems from CHF, published the following year—1941—one year before Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction—sounds at least in its section headings like something from Steven’s notes towards the Notes:

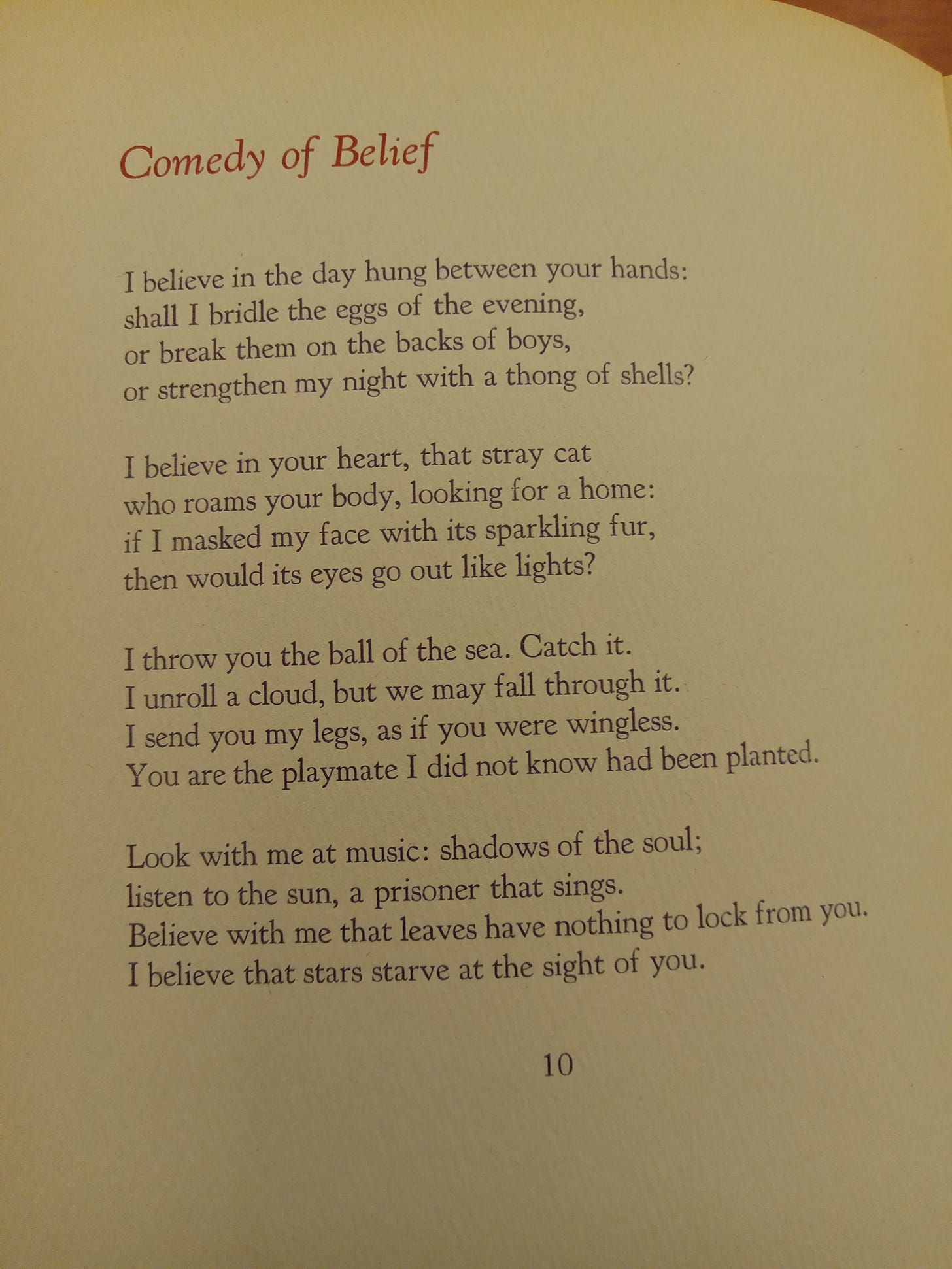

I love “The Comedy of Belief” as a title! As a poem, well… it crosses Stevens with elements of French surrealism and sound-effects downstream, I don’t know… from Swinburne? but without meter, shape, or taste…

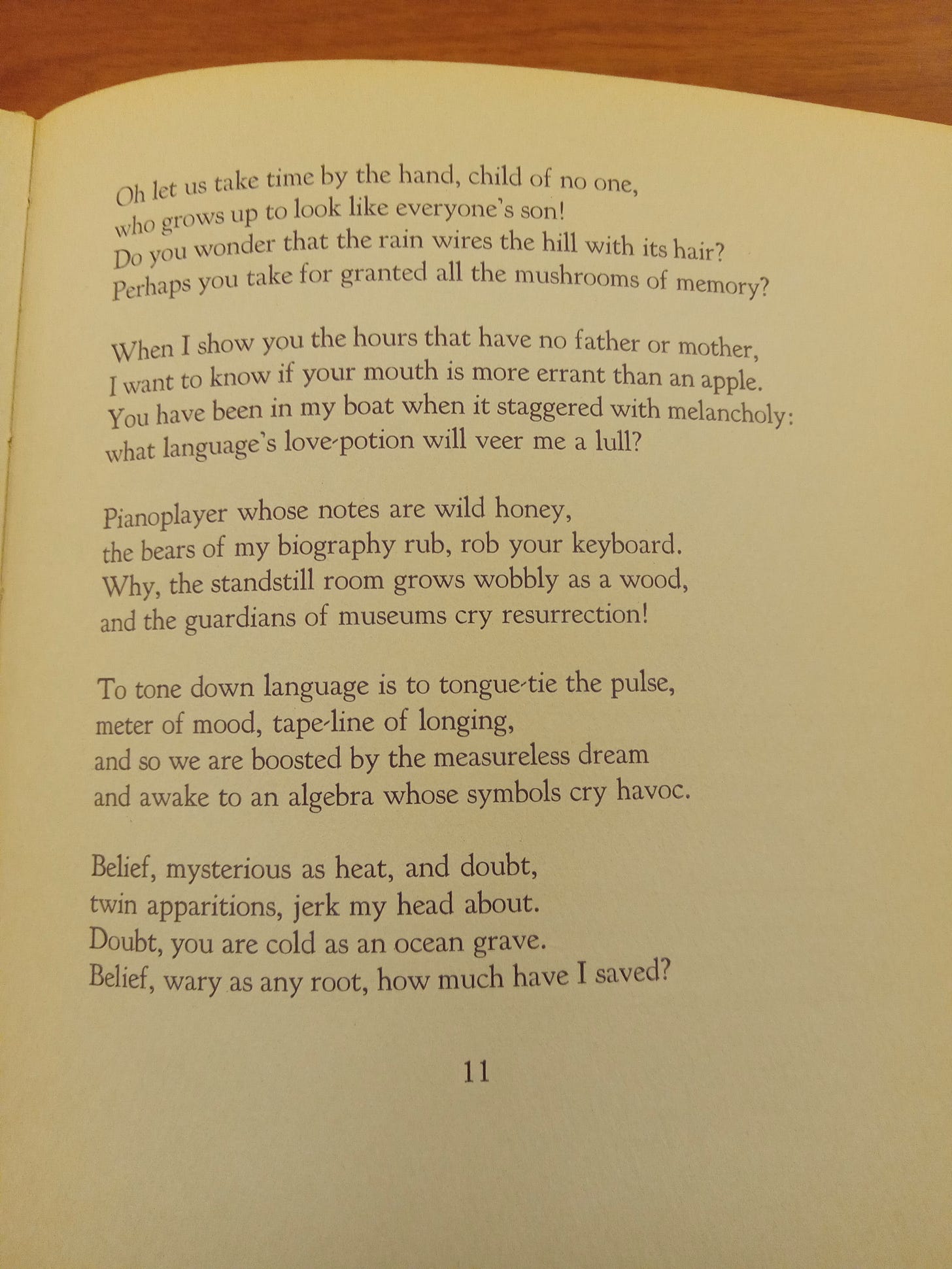

Ew. It keeps going for pages but I can’t, no more. I’d argue, however, “I throw you the ball of the sea. Catch it” and “awake to an algebra” are proper Stevens. And while I’m not sure what breaking evening’s eggs on the backs of boys actually involves, it sounds hot. What if Stevens were fruitier? is a question gay poets did spend at least a generation asking—and even Judith Butler has a fun article “The Nothing that Is: Wallace Stevens' Hegelian Affinities.”

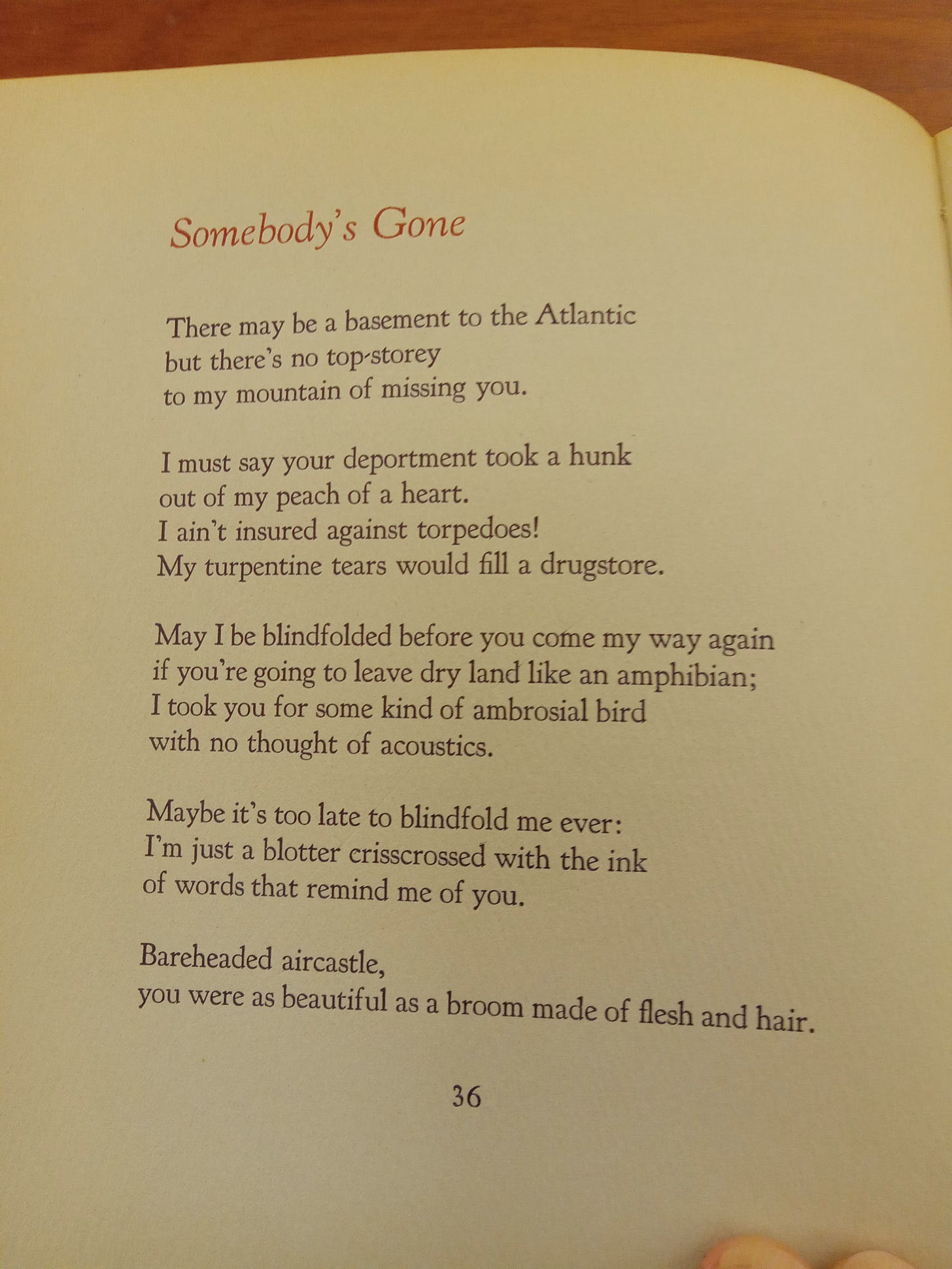

There is some awful prototenderqueer stuff here too:

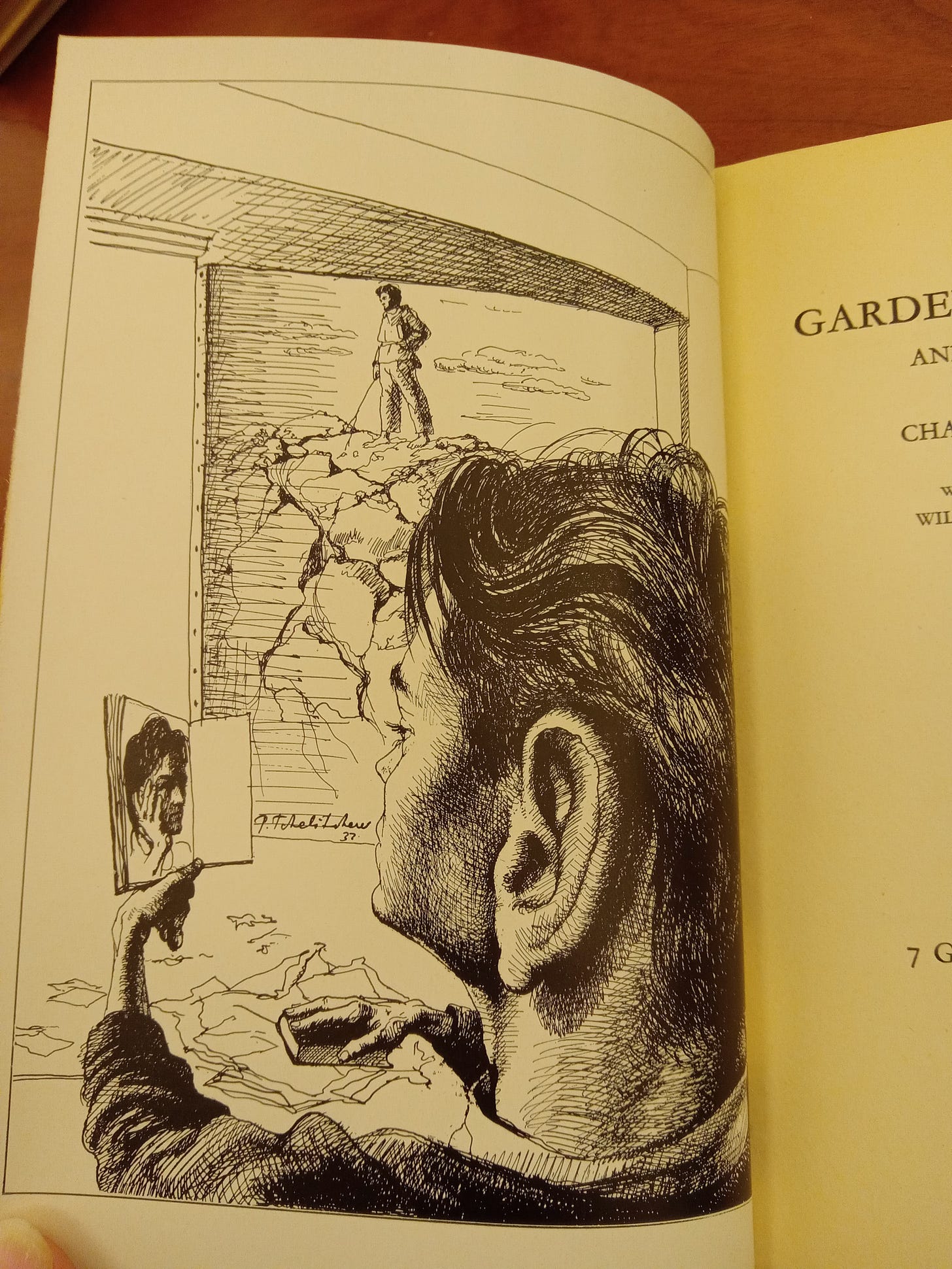

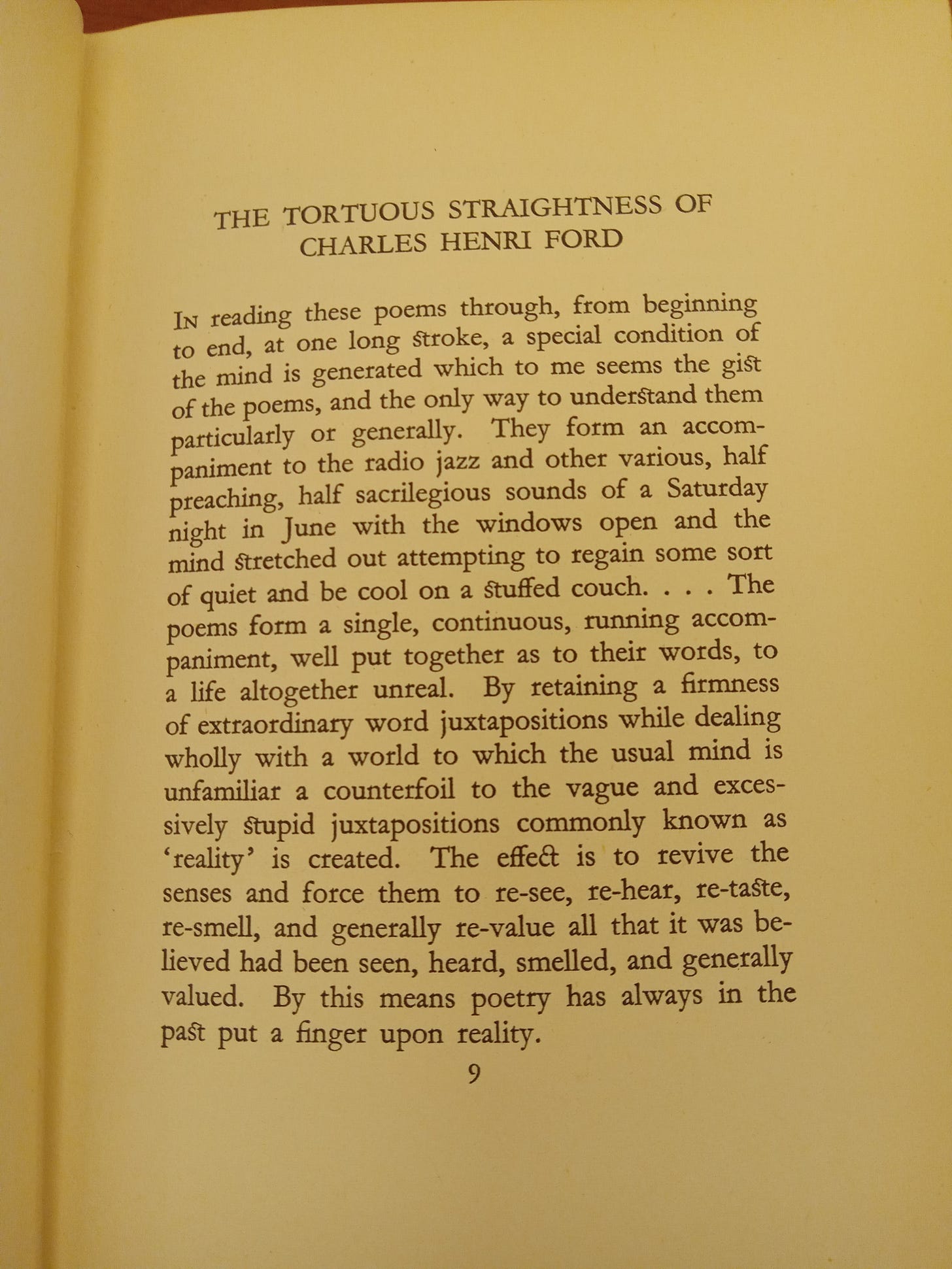

So CHF was not a great poet, but he had a great network. Besides Stevens receiving his books, he had Tchelitchew to illustrate them and William Carlos Williams (a frequent contributor to Blues and View) to praise their uhhh straightness?

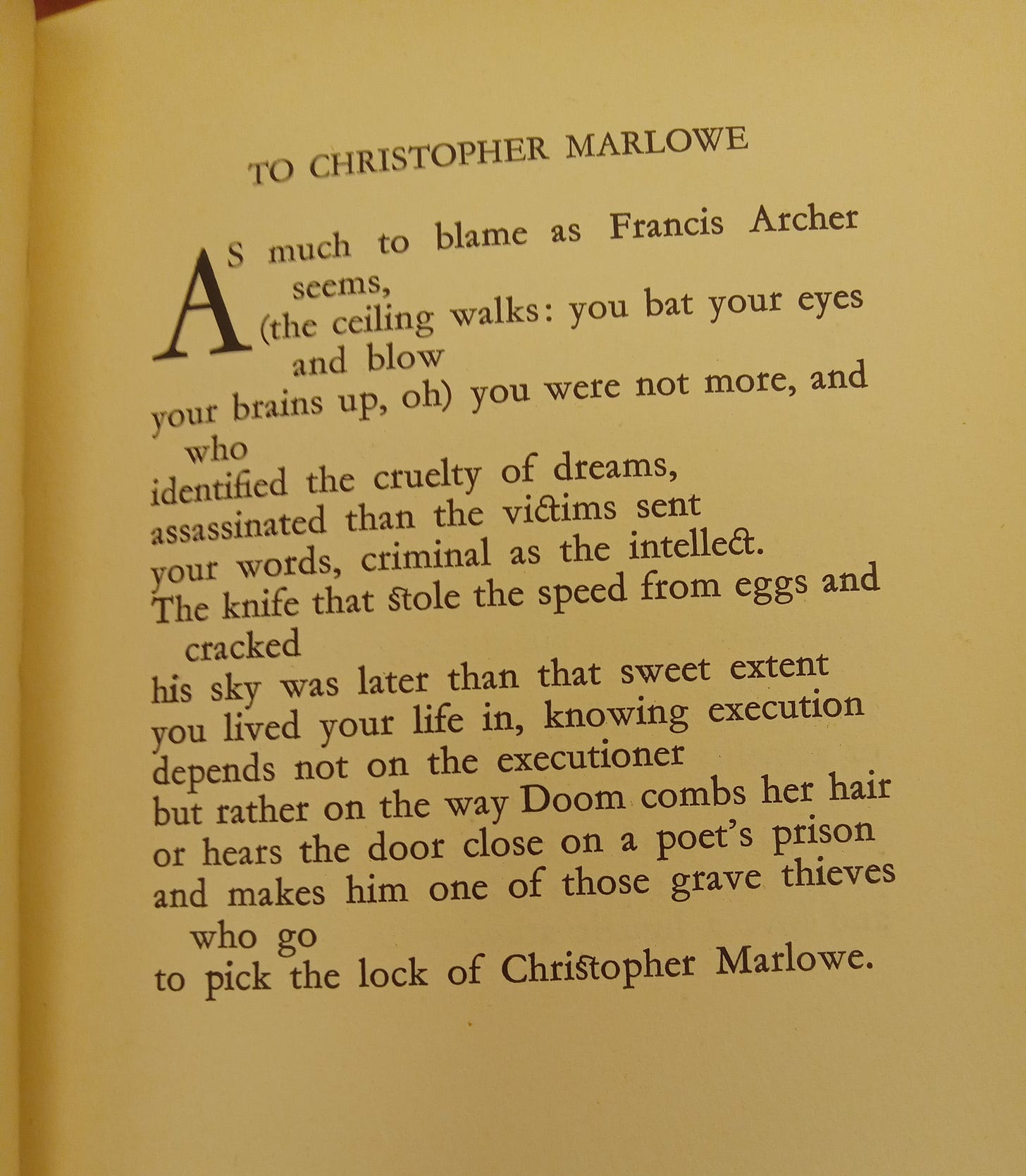

I love the nod to herstory of course (Marlowe was a queen, wrote about queen Edward II, and was an inspiration to Hart Crane and Derrick Jarman) but if only the poem were, you know, good (Francis Archer—but here I go explaining shit you could Google—was the guy who killed Marlowe).

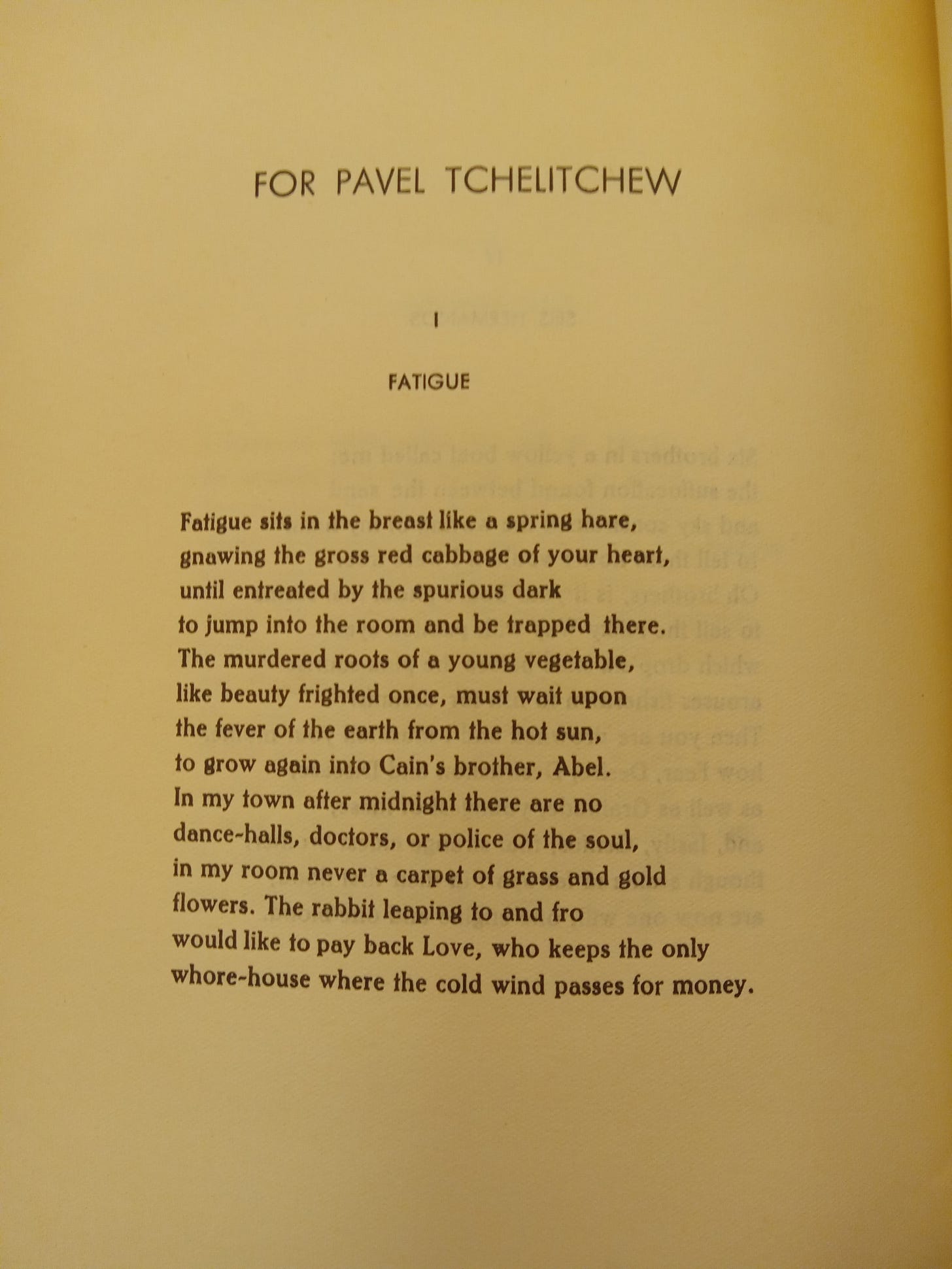

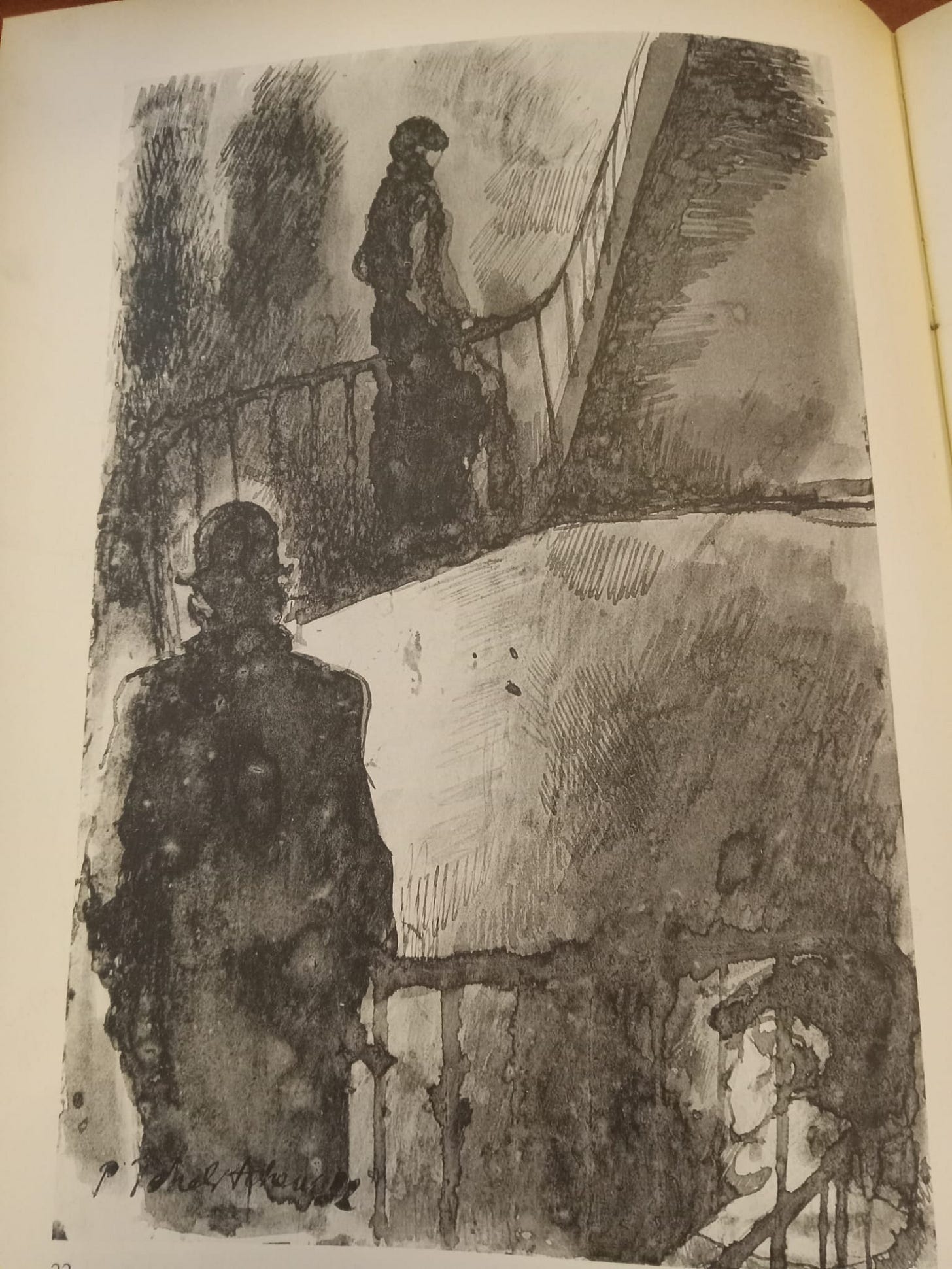

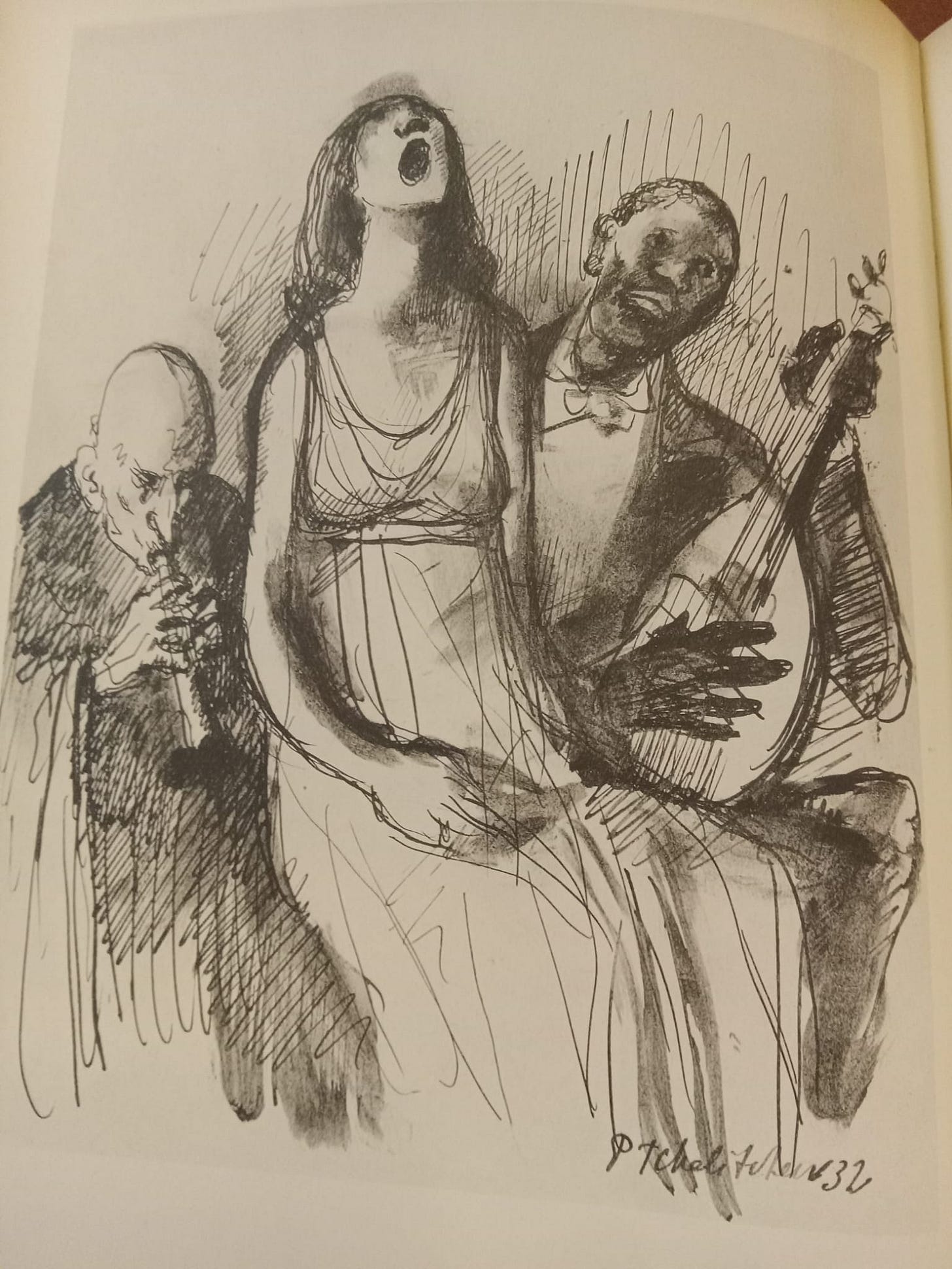

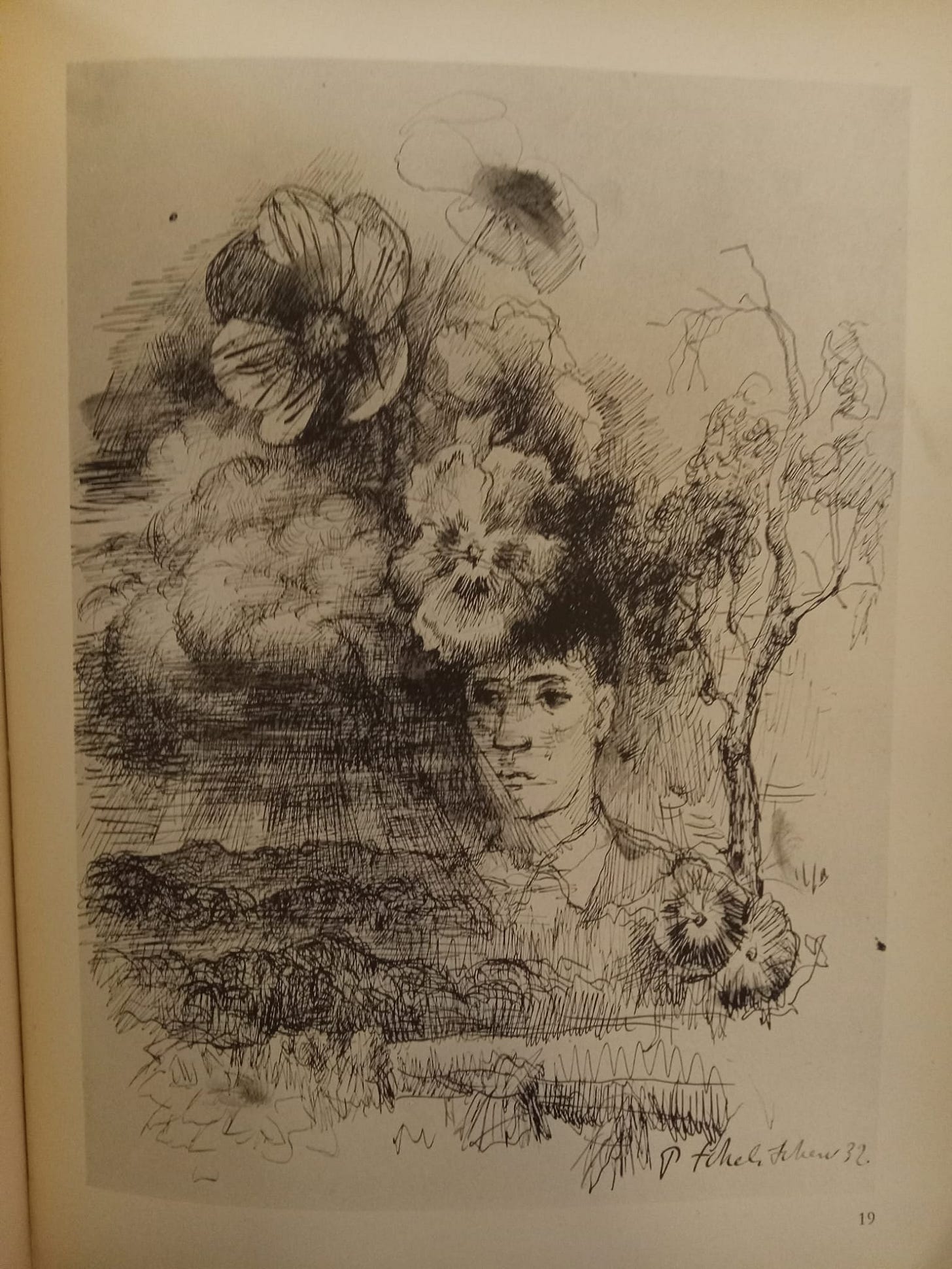

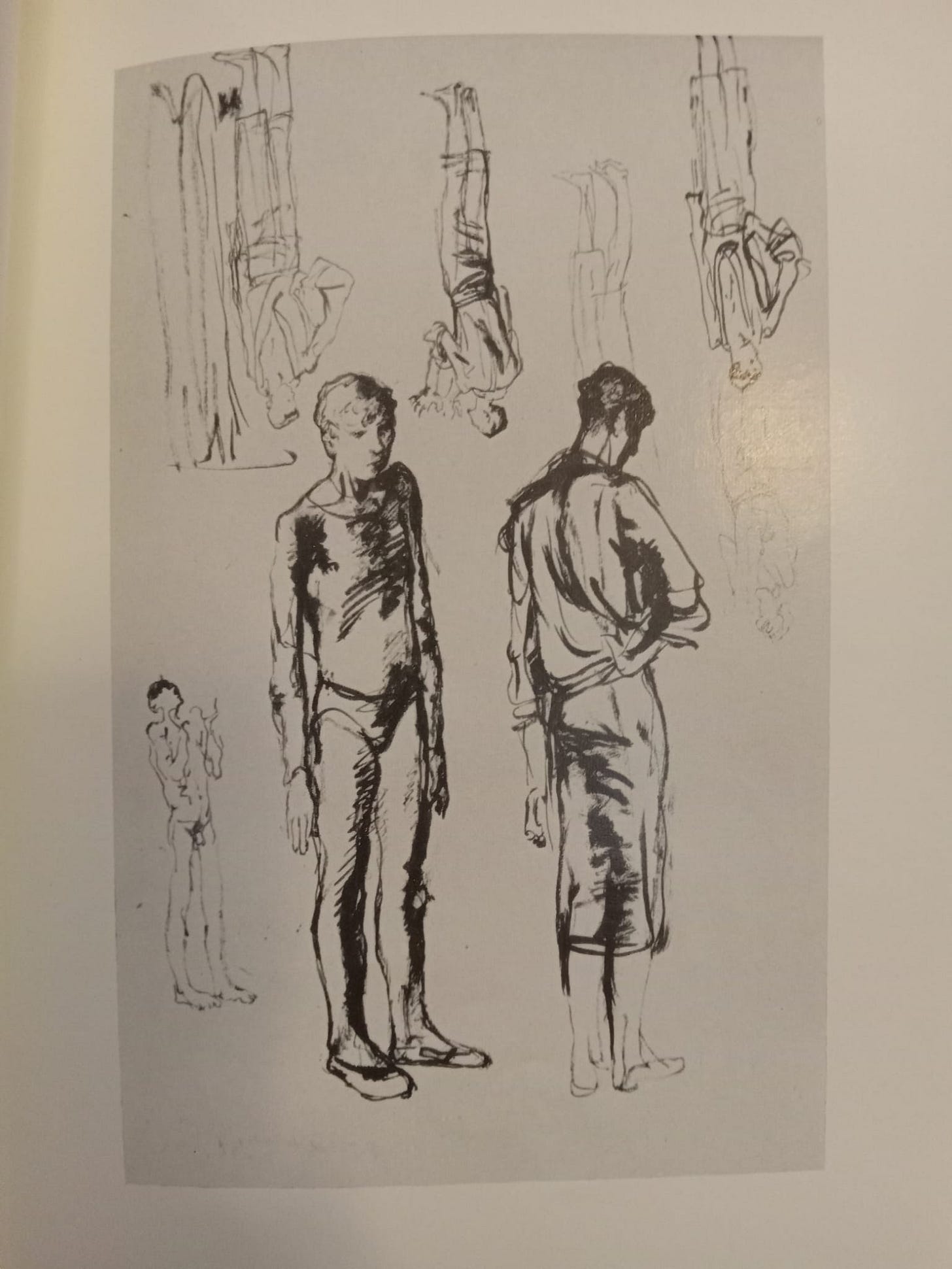

Tchelitchew illustrating CHF’s books seems like rather a raw deal for the illustrator—compare his drawing in Ford’s 1936 Pamphlet of Sonnets with the sonnet he gets dedicated to him in return!

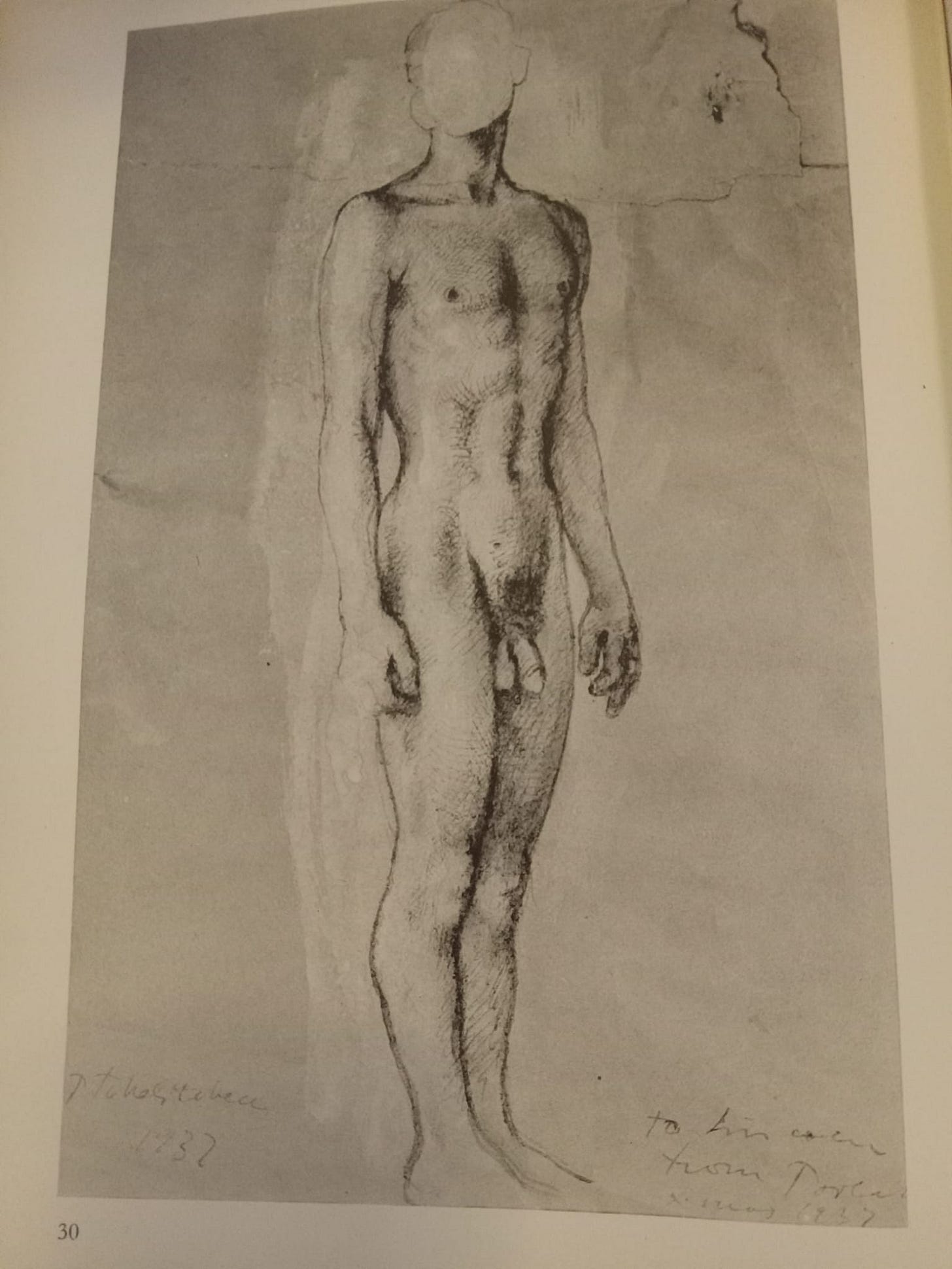

… let’s take a break from this bad poetry, in fact, and cleanse this post with some Tchelitchew-posting:

After that refreshment in “the active image,” back to CHF, but on to his magazine Blues:

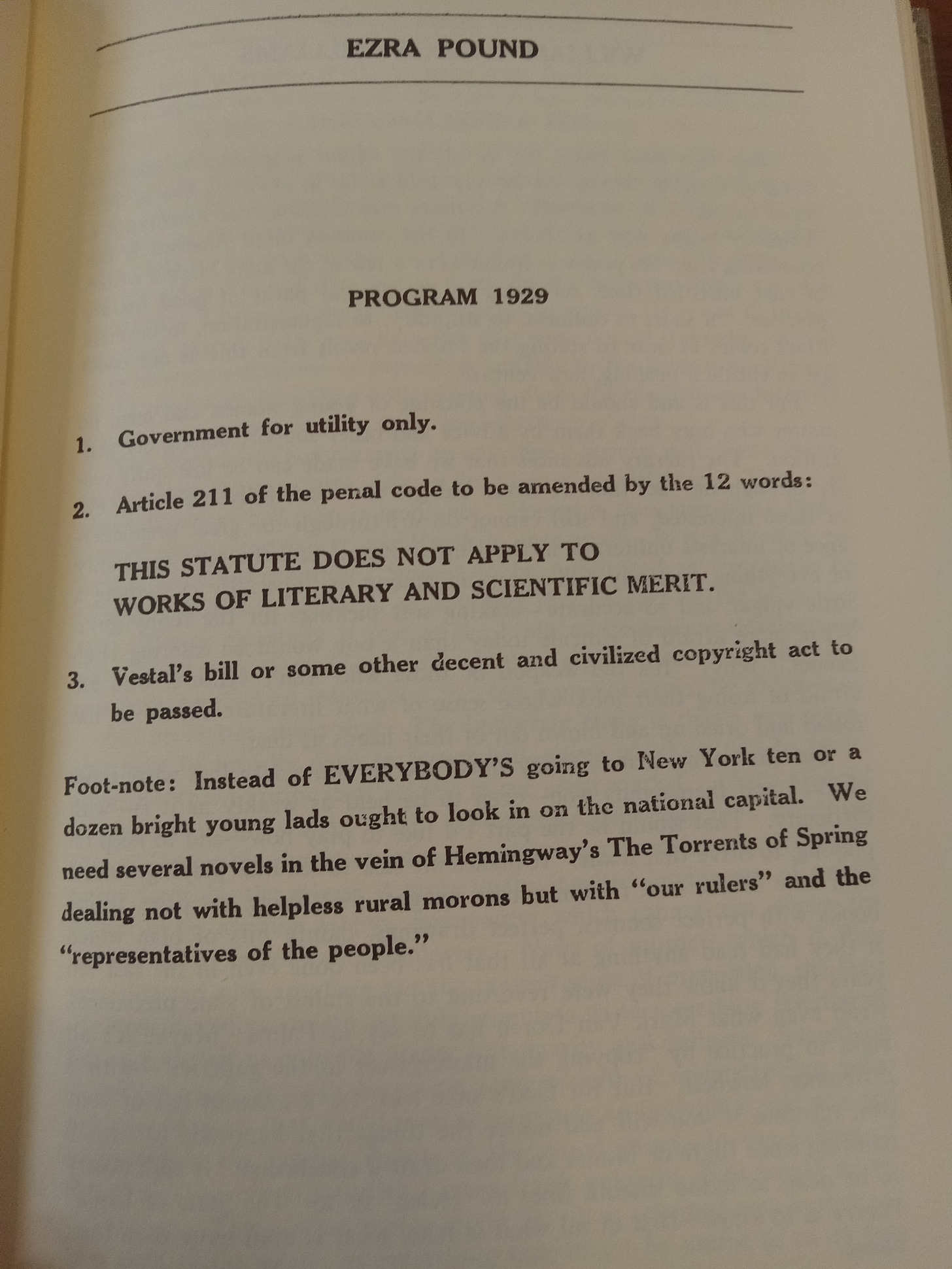

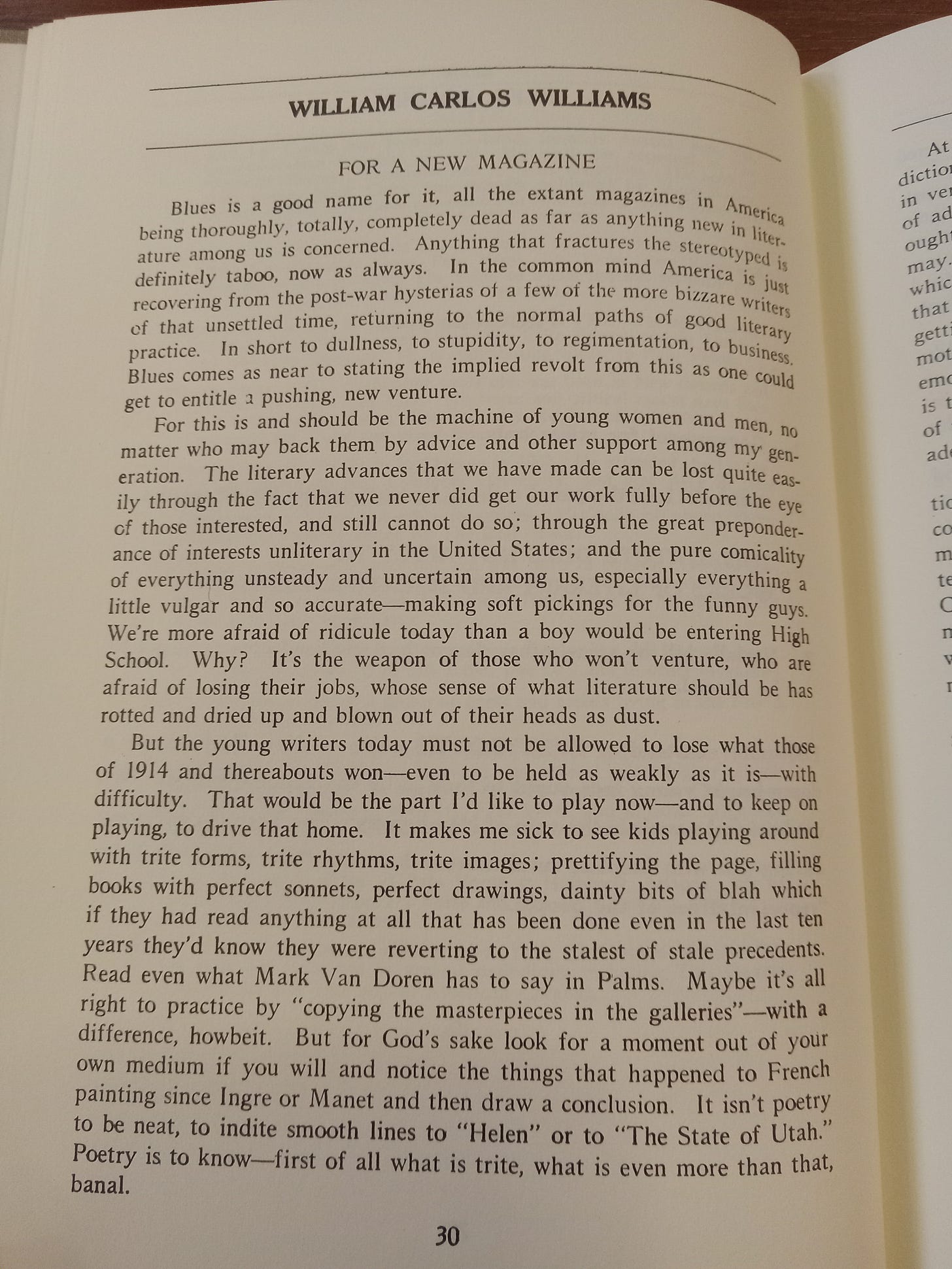

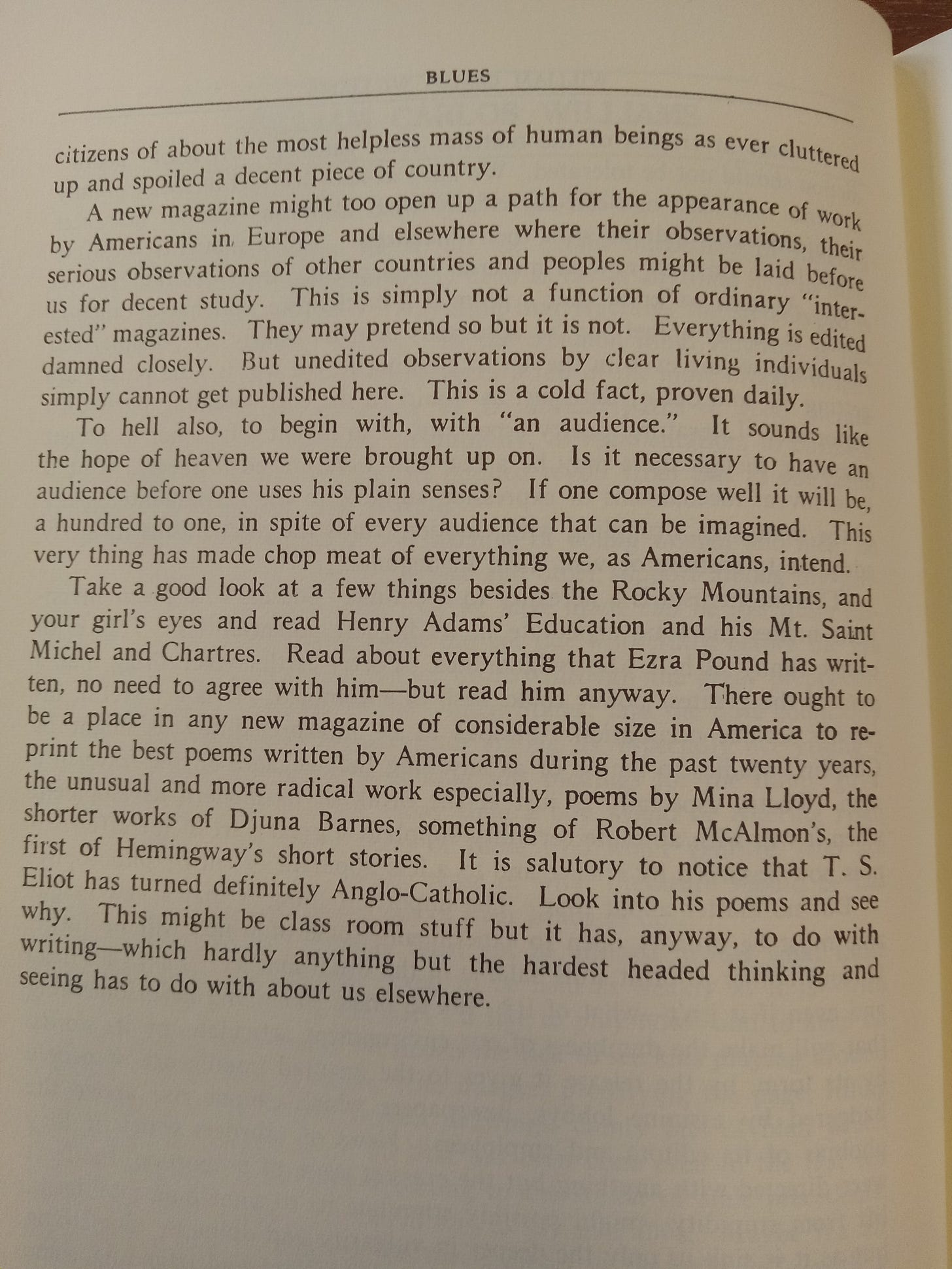

It’s full of declarations of the eternal avant-garde:

New York is over; we need a good literary magazine. Poetry is news that stays news!

Incidentally I’ve never understood what Pound and Williams were on about with their attacks on ‘literary’ ‘poetic’ diction (whenever anyone goes after inversion—or passive voice—I call homophobia); what’s more affected than their styles? But anyway, you can see that Blues got some big names—not bad for a Mississippi boy!

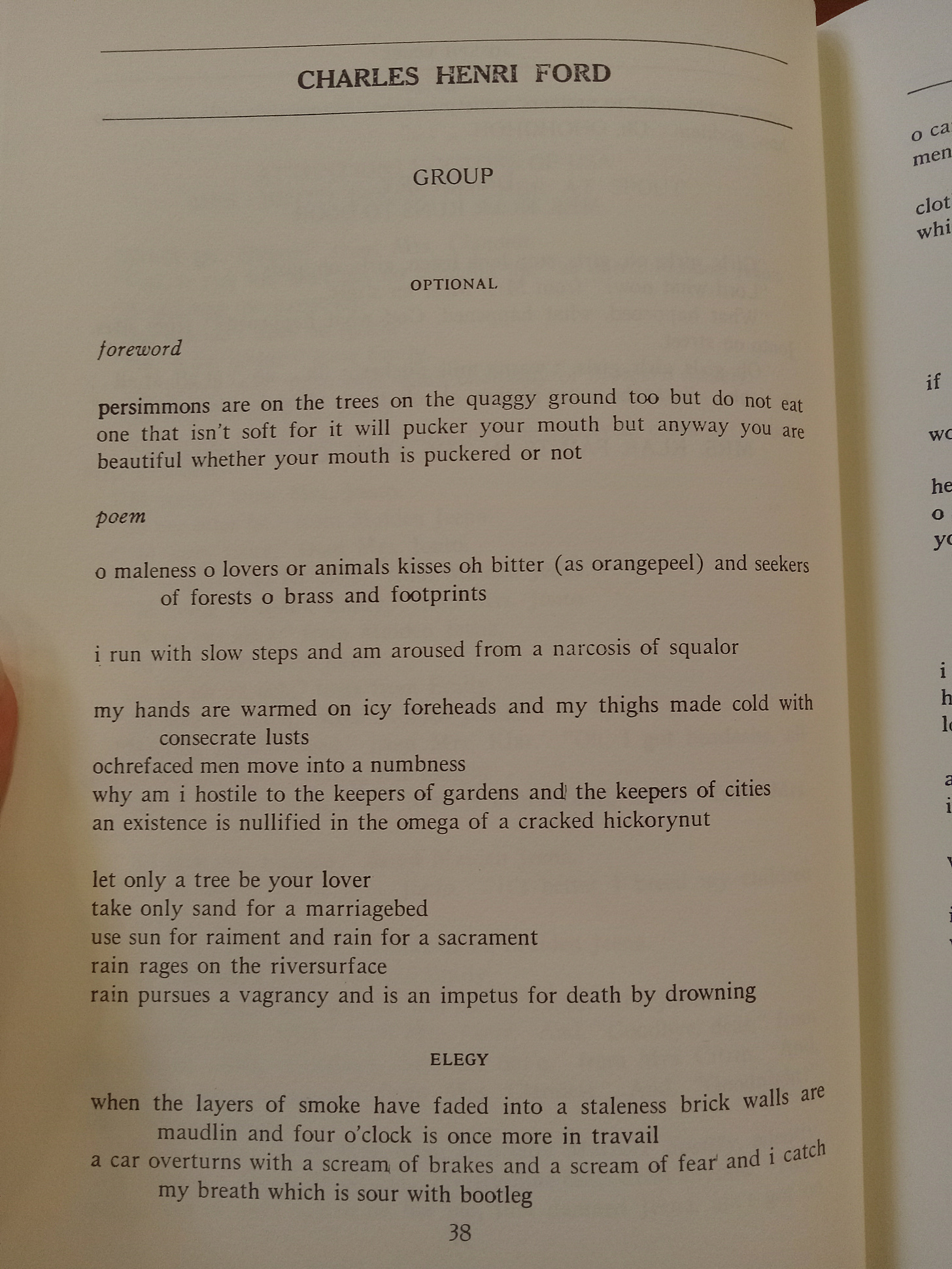

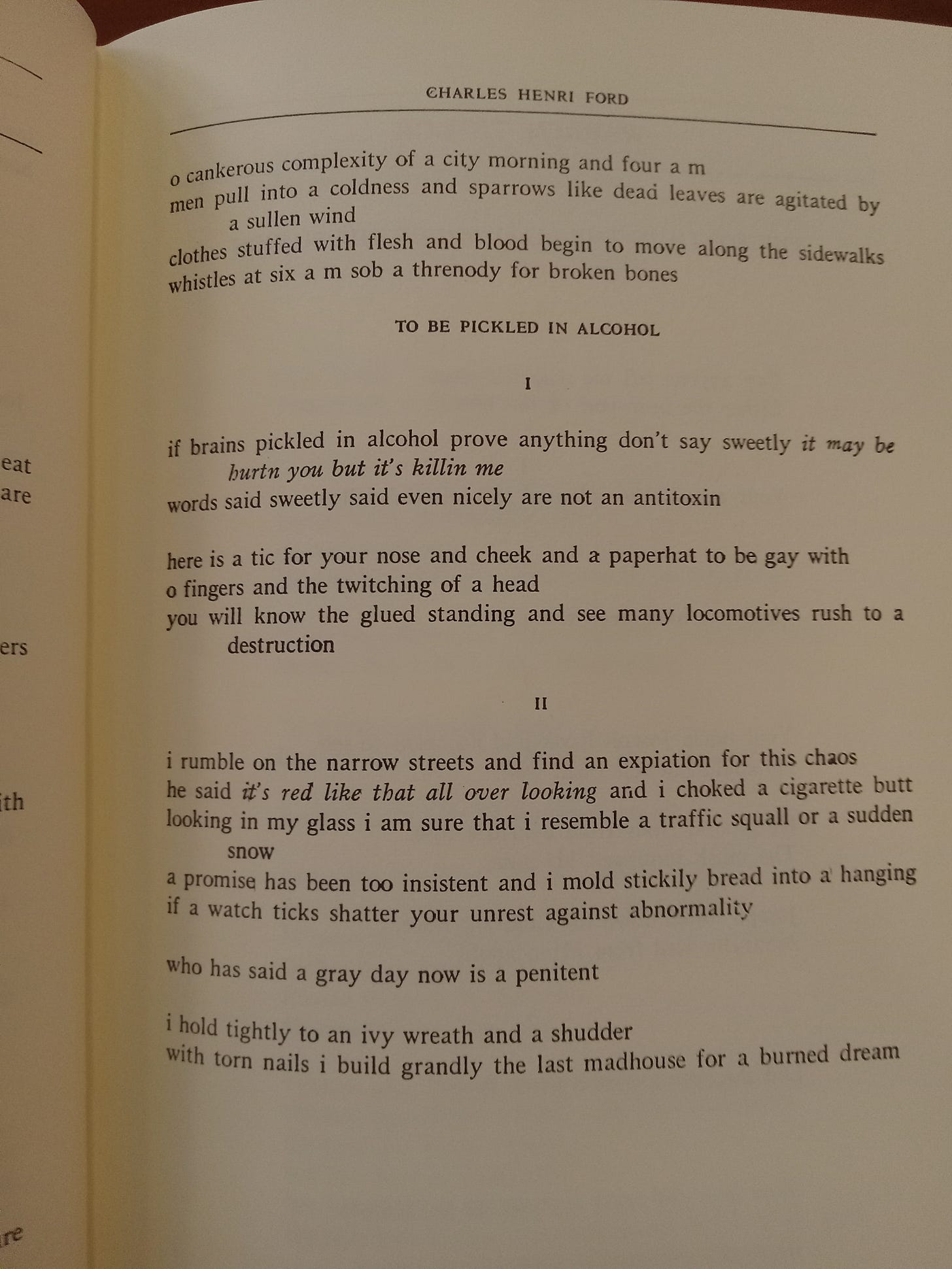

On the other hand he had to publish some of his own stuff…

I love the idea of an avant-garde and am momentarily seduced by the insistences of manifestos. But then what gets brought out as today’s (or even better, tomorrow’s) fresh urgent thing was already tired c.1930—so you can imagine how icecold I find your takes on Alt-Lit 2.whatever and the new internet writing.

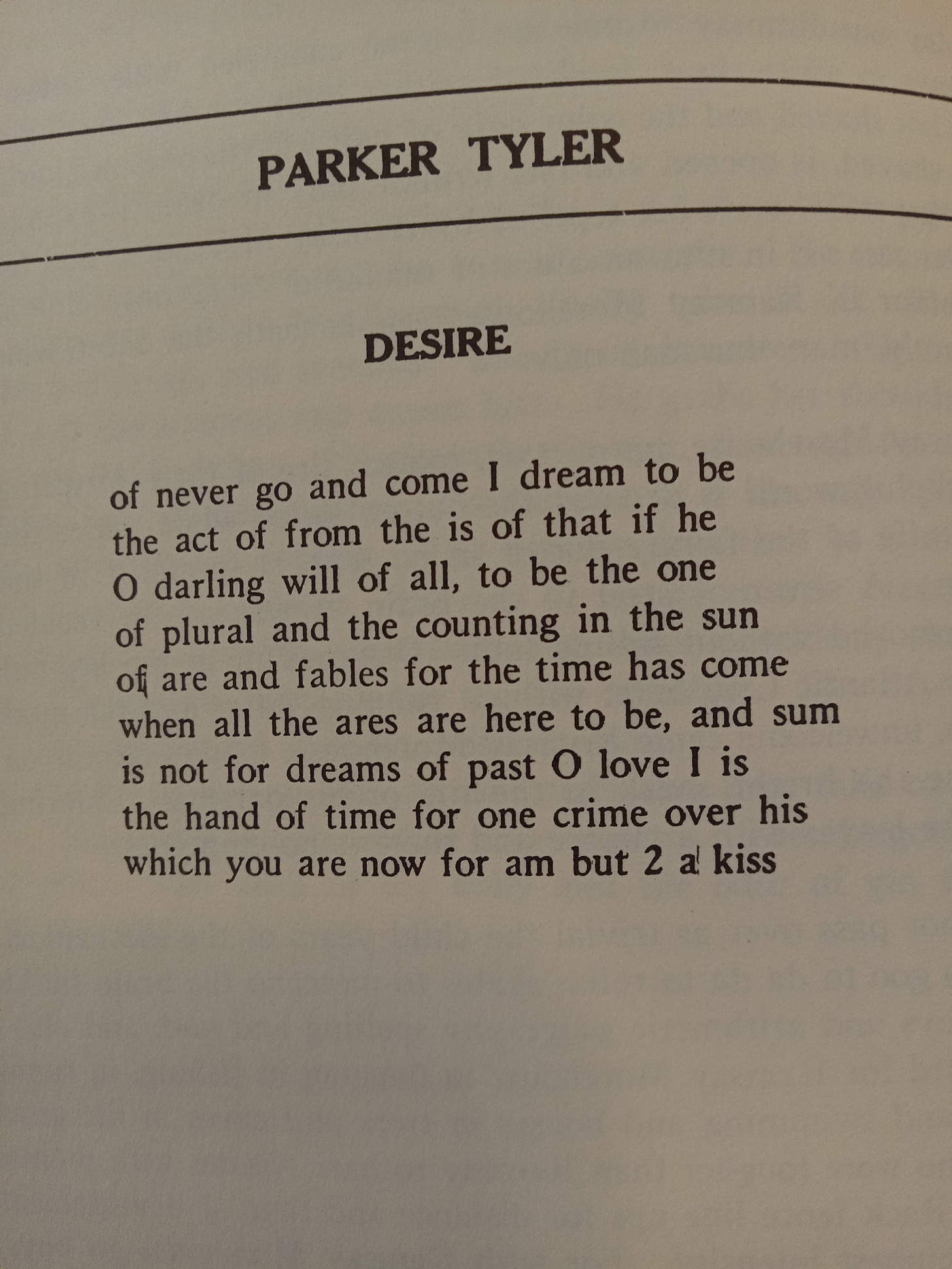

There’s some annoying writing by Stein, HD, Rexroth, Zukofsky, etc, which I’ll spare you (none of these are my favorites even on their best days!)—but here’s a mercifully short one by Tyler that reminds us good EE Cummings is also difficult:

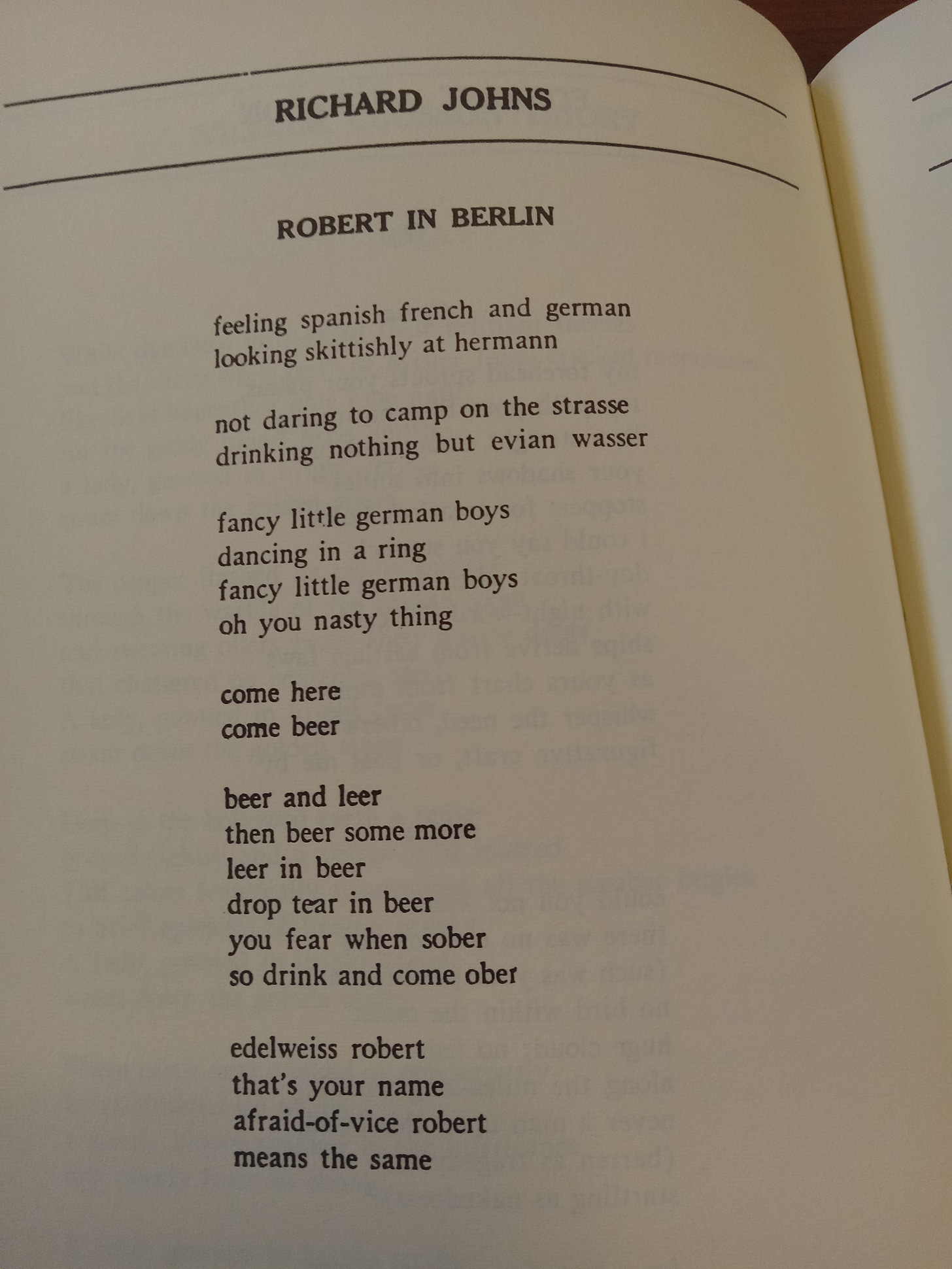

And one explicitly gay poem I actually kind of liked—by the founder of another little magazine Pagany (1930-33):

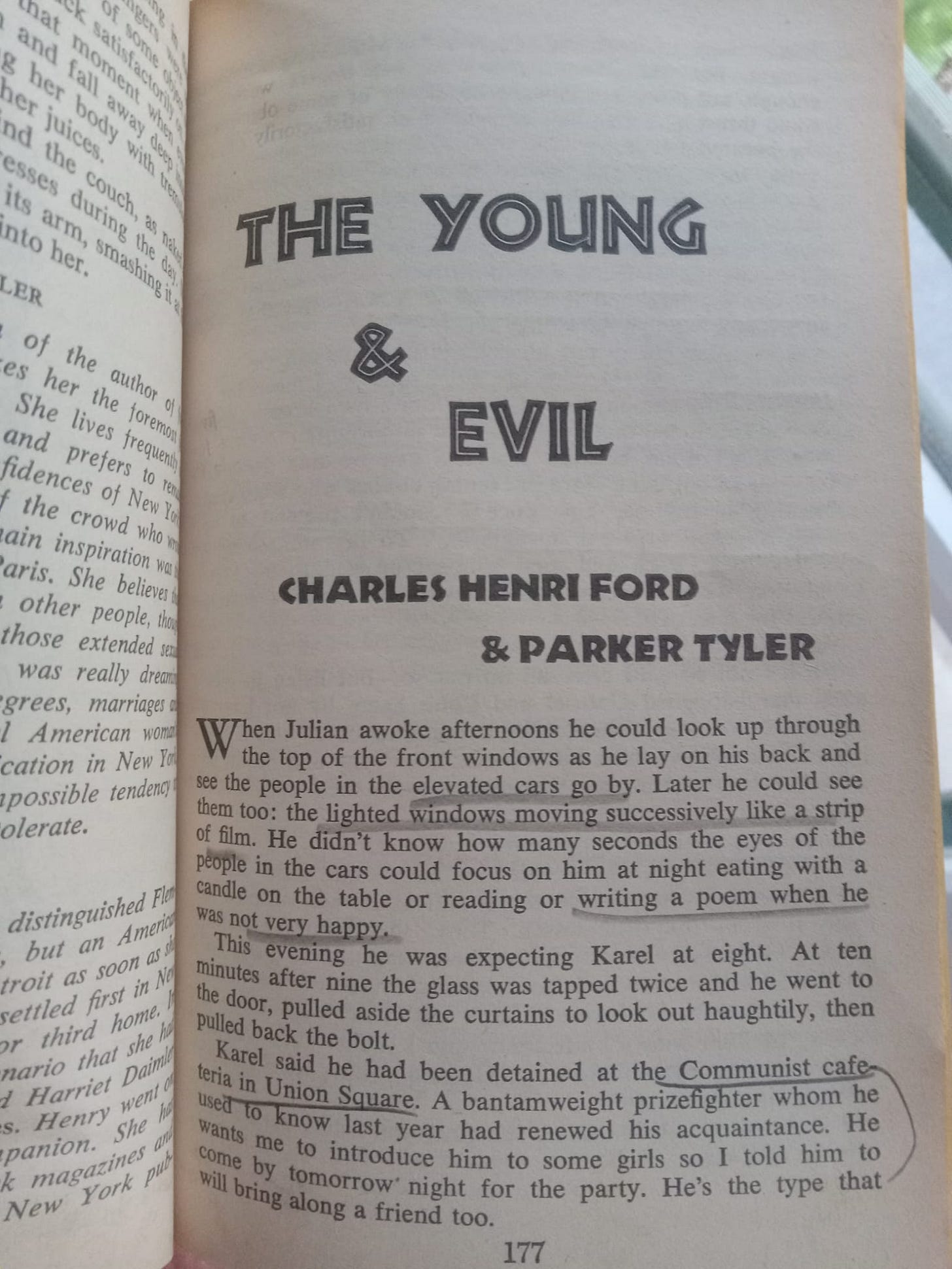

Blues published, and CHF wrote, prose as well as poetry… and I hate the prose even more lol! His most significant prose work is the novel he did with Tyler, The Young and the Evil (1933), which I’ve only read excerpts from the The Olympia Reader (1965). The excerpts did not entice me:

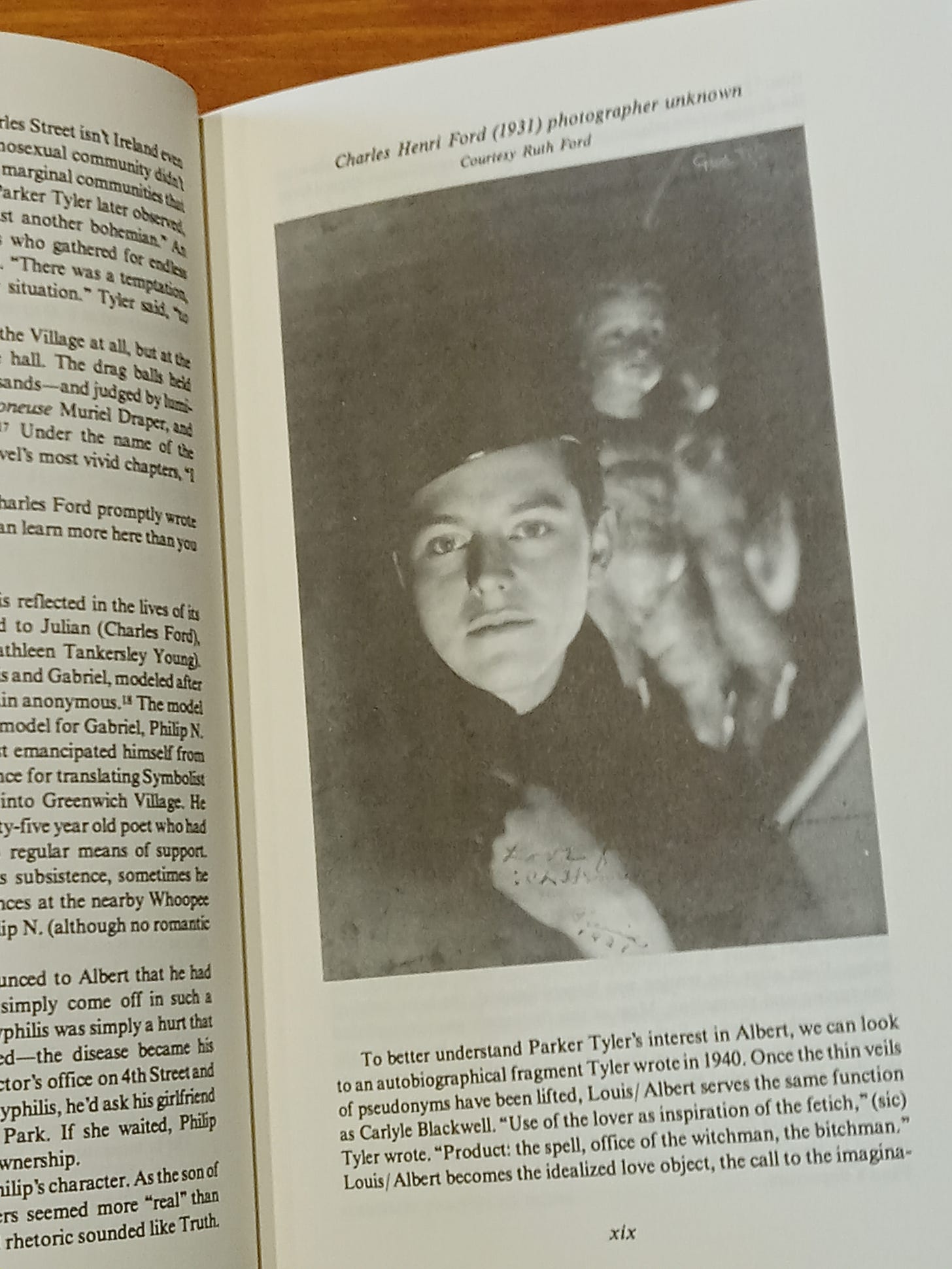

The Young and the Evil being terrible hasn’t stopped generations of gay guys from trying to find it interesting—and thus demonstrate their own critical prowess. Whether it’s the late Sam See or Dennis Cooper or Steven Watson in his introduction to the 1988 Gay Presses of New York edition, girls are using their big brains to turn shit into shinola! Here’s some Watson:

skipping merrily along…

Apologies for the blurs! Now this is all wonderful fun information I’m so very glad to have but I can’t help but feel a bit gaslit by all this brainpower being deployed without mention made that the novel isn’t good. It’s fine I think (because after all I do it) to spend a lot of time thinking and talking about gay cultural achievements that are mid or just shit; they’re ours, they’re interesting, we love them and love to hate on the and we don’t have to turn off the part of our brains that can tell good from bad!

By all means—but protect gay criticism, too!

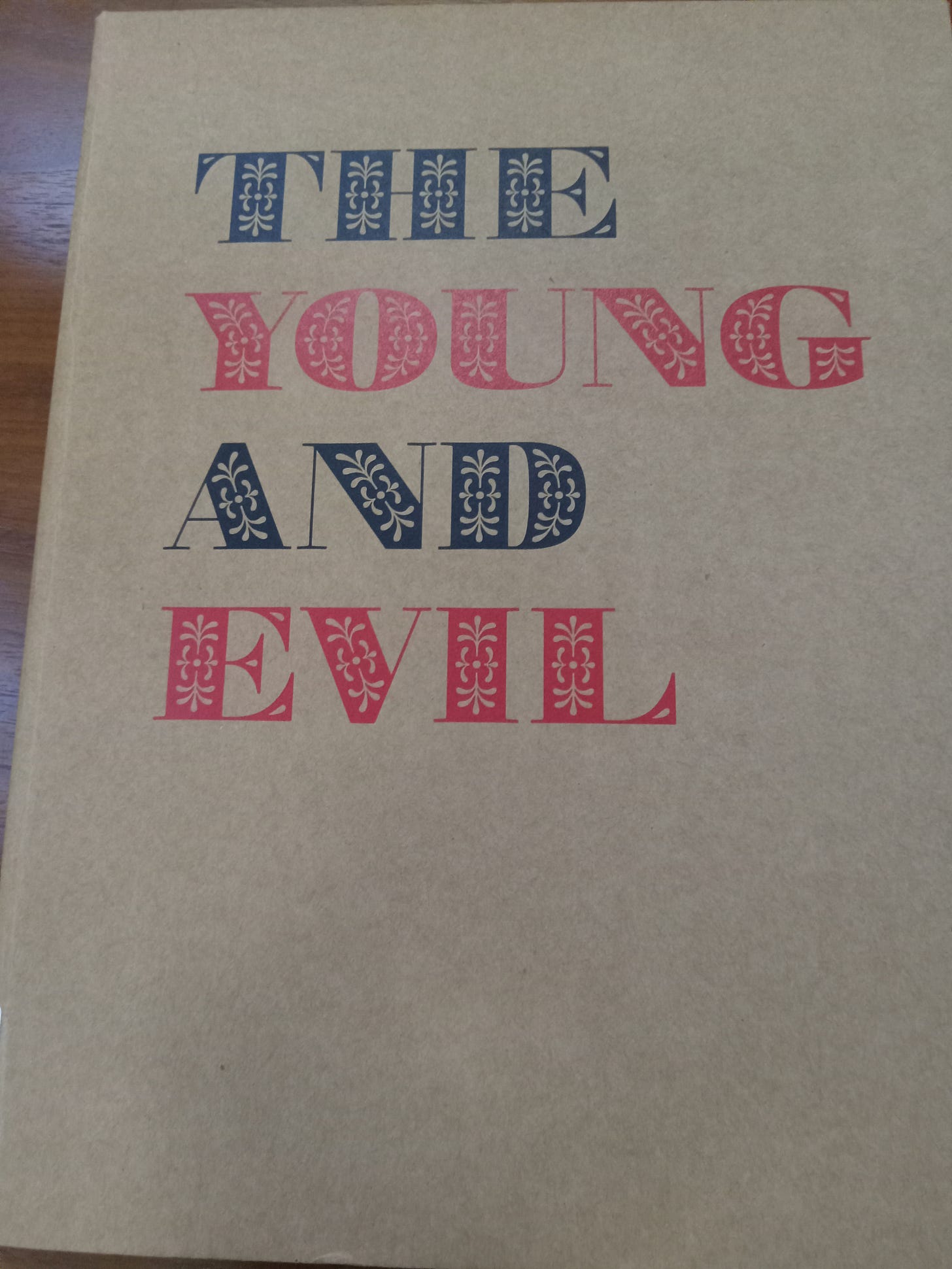

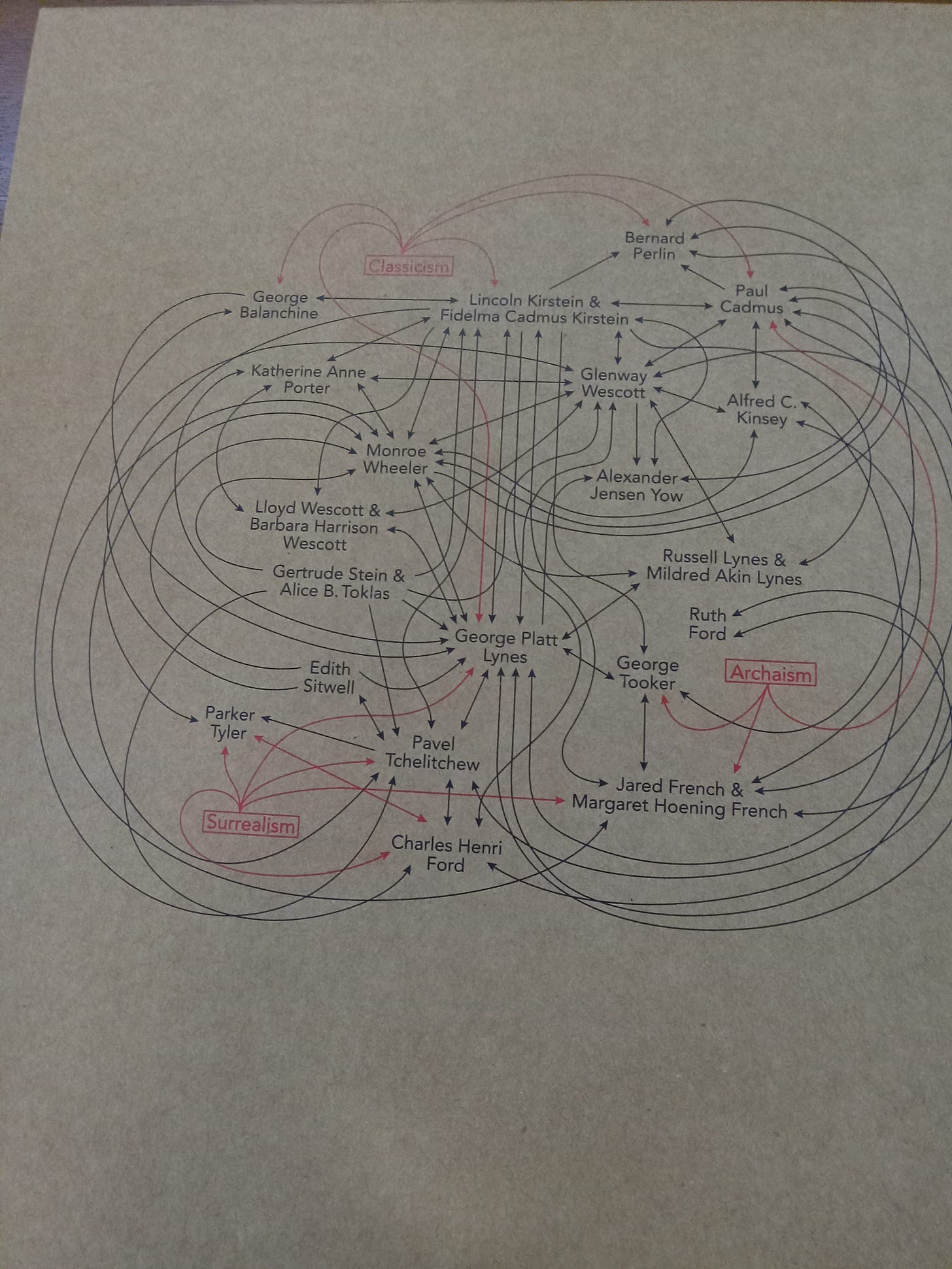

Not least from the gay critics-cum-curators. For instance, Jarrett Earnest did a show at Zwirner titled, and ostensibly organized, around The Young and the Evil, leading to this 2019 book—which, I must say, is a cool object that I’m glad exists to document and introduce people to some interesting artists, a few good ones, and a lot of ho/mediocrities connected by what the back of the book so accurately shows are noodly vibes:

It’s giving the Powerpoint that lost us the war:

Earnest’s show and book brings a lot of things together, clearly—and works by suspending judgment about which ones are good. Instead his intro does some kind of Guy Davenport type conceptual free association about magnets and Etruscans:

I suppose it’s only appropriate that since, like the founding figures and arch-publicists of such literary scenes as The Beats or Dimes Square, Ford was not himself a skilled writer or thoughtful judge but an excitedly indiscriminate vibes-machine, he should be remembered through a mist of gush and puff by which criticality is evaded.

And maybe after all we need such overheated zhooshy idea-confetti and refusal to notice differences in quality in order to constitute the networks, scenes, energies, feelings etc that make actually good writing possible (although I usually think this prevents us from having the judgment writing requires, I’m willing to consider the alternative!). I have to be grateful, for instance, that Blues published this dumb story by a then 23 or 24 year-old Harold Rosenberg, who would spend another decade writing bad stories and poetry before finding his voice as a critic:

Ugh, my vertigo is growing so mighty I can’t post any more of this—good night!

I'm liking these Christopher Street bios

Nice photograph of Stevens, open faced, almost in the middle of saying something. Stevens though of the Oboe, August and Summer’s Day, not Guitar. Tchelitchew seems stuck in Picassoland 1903. Wonder what O’Hara thought of that Kirstein/Zwirner group of painters, Cadmus, French, Tooker (though drawing of Monroe Wheeler is fresh). Think of them alongside O’Hara’s Jane Freilicher, Alex Katz, John Button, Grace Hartigan. Difference - same with Ford & Parker maybe - is they don’t question the medium they’re working with, let the materials/ words have the upper hand. Seem prefabricated perhaps.

Thanks for the tour of Huntington rarities, first issue of View, etc