I haven’t paid much attention to gay erotica, at least, much critical attention to historical gay erotica (I do love nifty.org! and anyone who thinks our ‘literary’ gay authors are transgressive or interesting for their frank depictions of sex and desire—whether it’s Greenwell or Cooper or whoever—should check out some of the better nifty stories to see how it’s really done), mostly because so much of it is repetitive, same-y, and dull—like any genre fiction or porn. I don’t even care for the work of John Preston or ‘Phil Andros’ (Samuel Steward) which is supposed to be a higher-grade version. Seen one, seen ‘em all.

Except! At the urging of a local archivist I worked through some of the 60s-70s pulp novels of Carl Corley, a Mississippi gay author who, astonishingly, wrote most of them under his real name. And they’re of interest, at least to me, because almost all of them, as you’ll see, are set in the South—and in a specific south ranging from rural Mississippi to Baton Rouge and New Orleans, around an archipelago of bars and cruising grounds (with some excursions to prisons, the military, the frontier past, and, in one case, post-war Japan). So, I’d like to insist, this is Southern literature, or at least the small percentage of scene-setting in the novels is (it’s mostly fucking or building up to fucking).

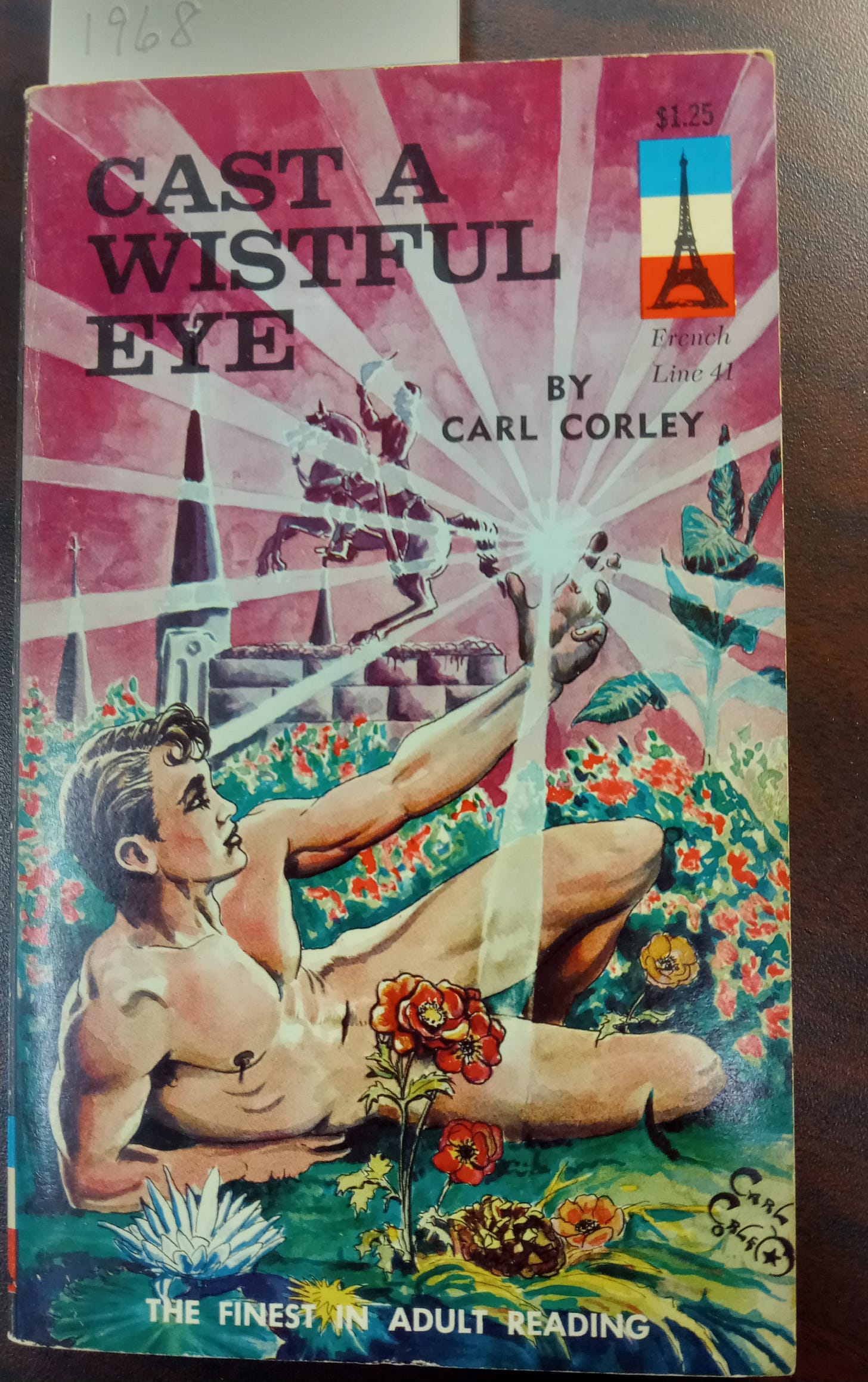

There are people who work on this sort of thing. Michael Bronski has a good book on gay pulp fiction, most of it semi-pornographic, from the mid-century to Gay Liberation. Robert Maril has an entertaining podcast reading some of the ‘better’ ones aloud (Gay Whore is my favorite), ‘better’ here meaning ridiculous, sexy, and in some way giving representation of the scenes of gay life (bars, Fire Island, etc) from the period. And a researcher, bless her, has put together quite a comprehensive page on Corley—including a gallery of the cover art, which he drew himself.

So I’ll just share a few choice images before getting on to the Southern elements—because, obviously, that’s what you want to read about, is the regional aspect (I’ve actually dreamt for years about doing a project on nifty.org stories looking at how they set sex in various places and eras—there’s a whole section of ‘Historical’ fiction, and don’t you want to know which is the sexiest era? or beyond plumbers and pizza men, which are the sexiest professions? where is our libido now? I do wish often, in the same spirit, that psychoanalytic commentary on contemporary culture/sexuality were not the preserve of the fools at places like Parataxis, who want to sell you their merch).

Ok, some covers!

You get the idea. The Southern element chiefly comes in at the beginning of the novels, and at the beginning of particular chapters, where Corley is setting up vibes. First, rural Mississippi—which is either a small town or ‘the farm.’ This is of biographical relevance to yours truly because my father comes from such a place, down state, and indeed we’d call going there (a non-town with dirt roads) ‘going to the farm,’ although by that time nobody farmed anymore. That’s where I learned to ride a four-wheeler, a shoot gun and eat a squirrel. She’s butch!

foamed over with fragrance! You will have noticed this is all quite purple gushing and over-wrought—so imagine how the sex-scenes are. Markers of ‘the literary’ inherited from the Victorian age that have become signifiers of pulp trash. I haven’t read enough of the scholarship on this sort of thing to know what there is (recommend me!) on how genre fiction relates to ‘the literary,’ and how certain kinds of straining towards effect in prose come to be taken at a given moment as ridiculous while others are experimental, bracing, etc—let alone to know how those changes track with the evolution of styles for writing about sex (Corley’s sexual vocabulary is lush but opaque and hard to imagine jacking off too, but I bet people did! Maybe they found this frothing nonsense hotter than they would have the ‘directness’ of our own sex-writers [I certainly don’t get it up for Greenwell’s prose!]).

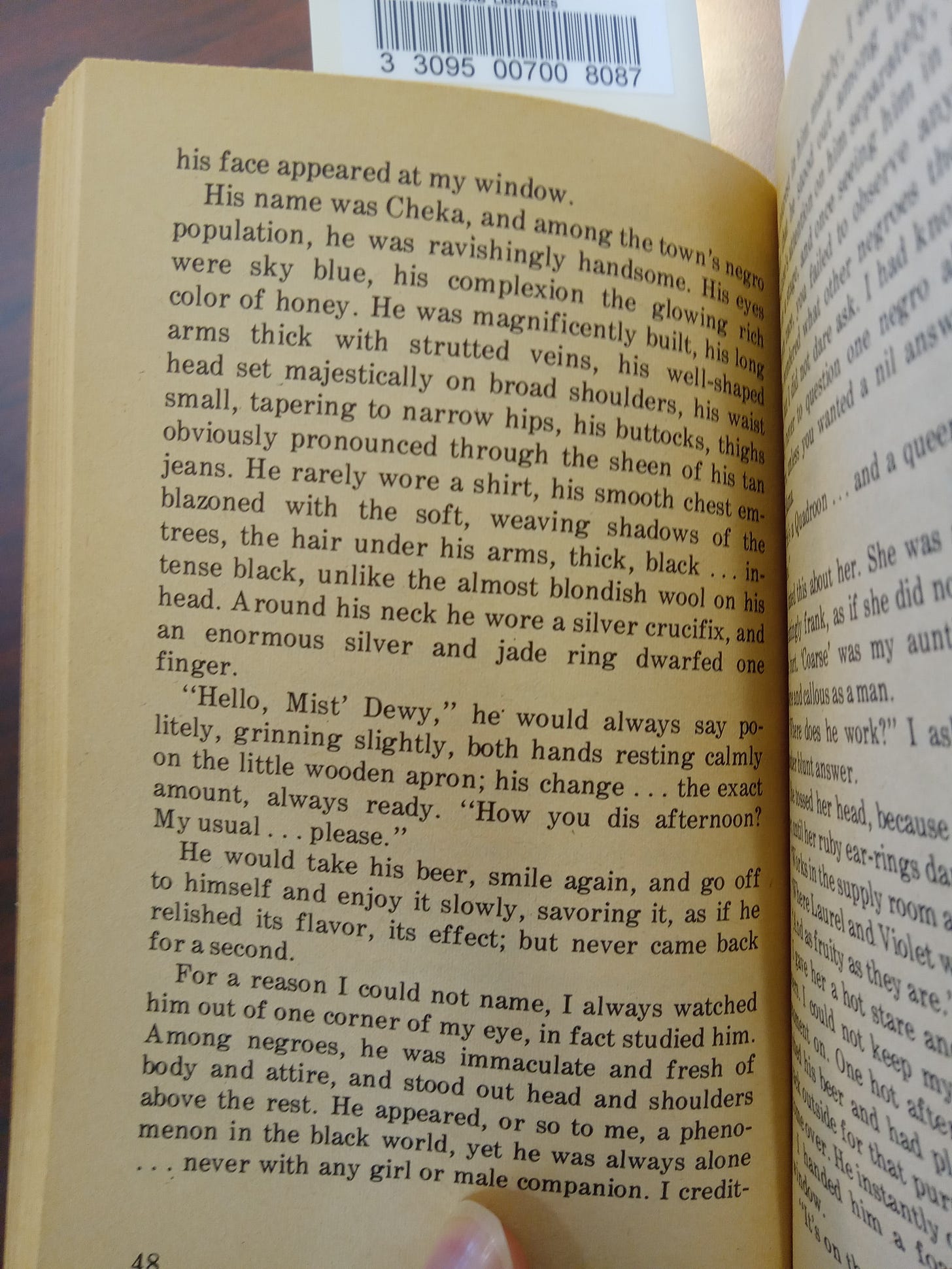

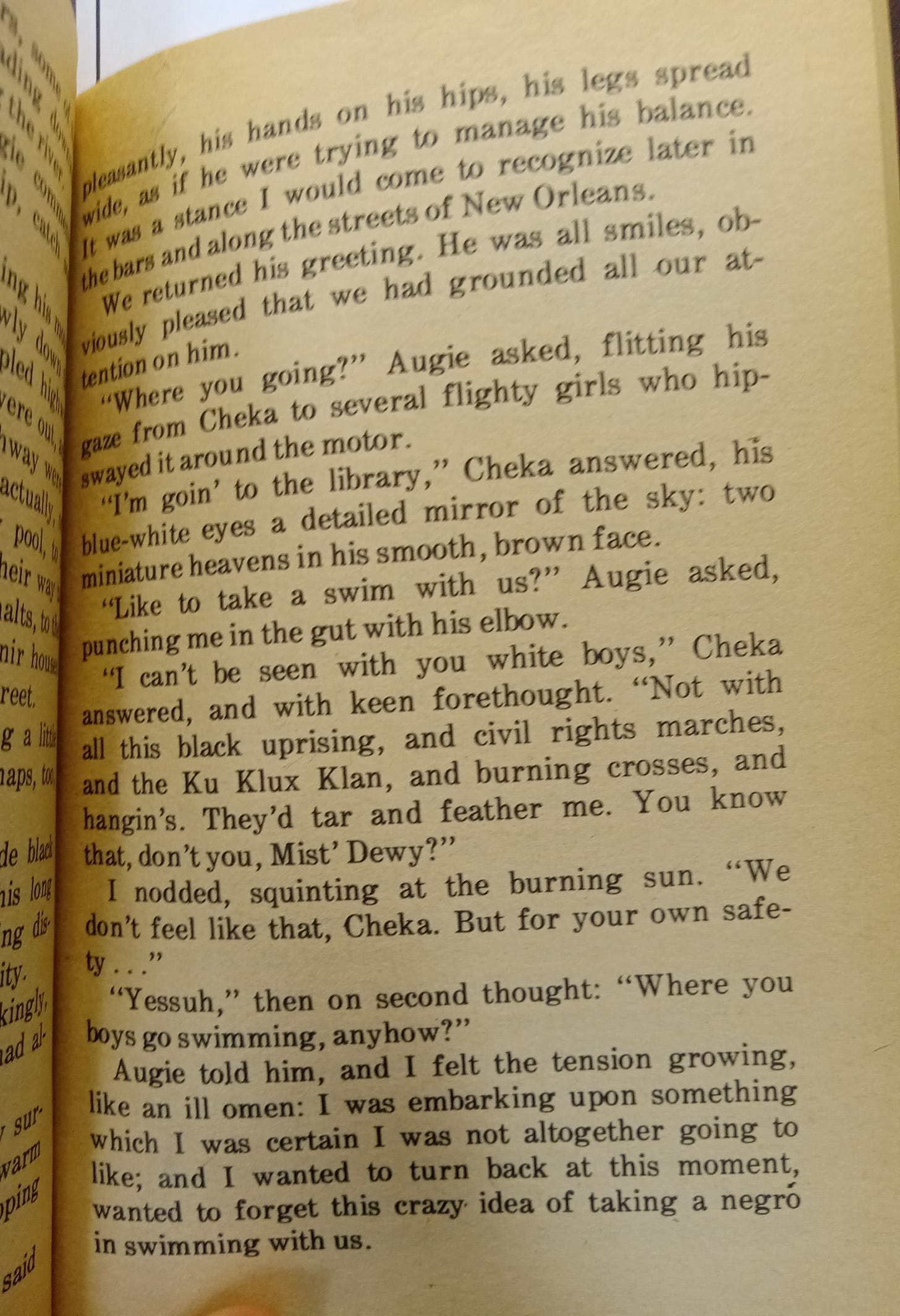

Race figures some in the books—the main characters or love-interests are often vaguely exotic, with some European (French, Spanish, Greek) or Native American tinge (and in my family too, there was talk of a Cherokee princess back somewhere). But also a bit of sex between white and black men.

The French Line press didn’t have sensitivity readers.

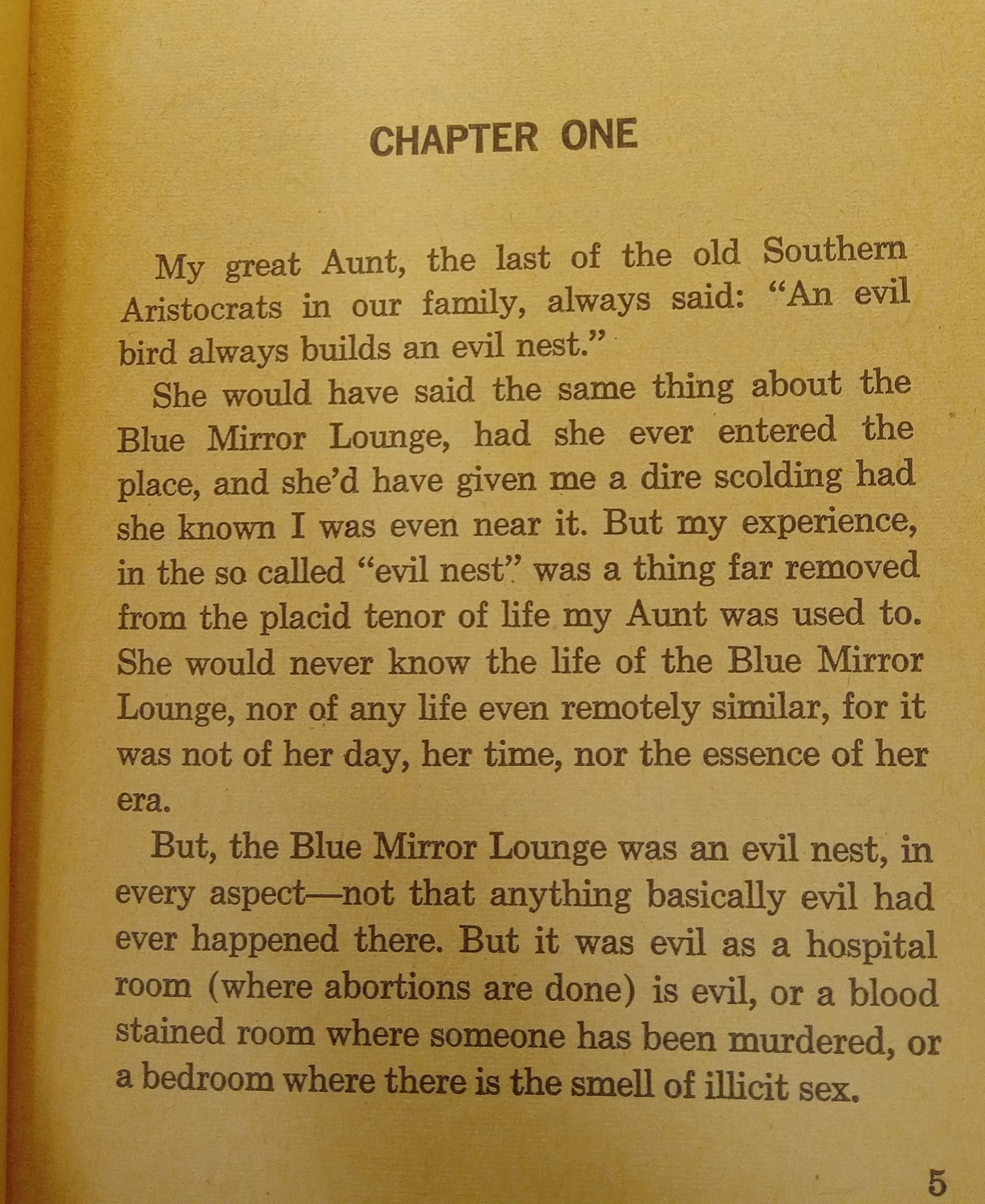

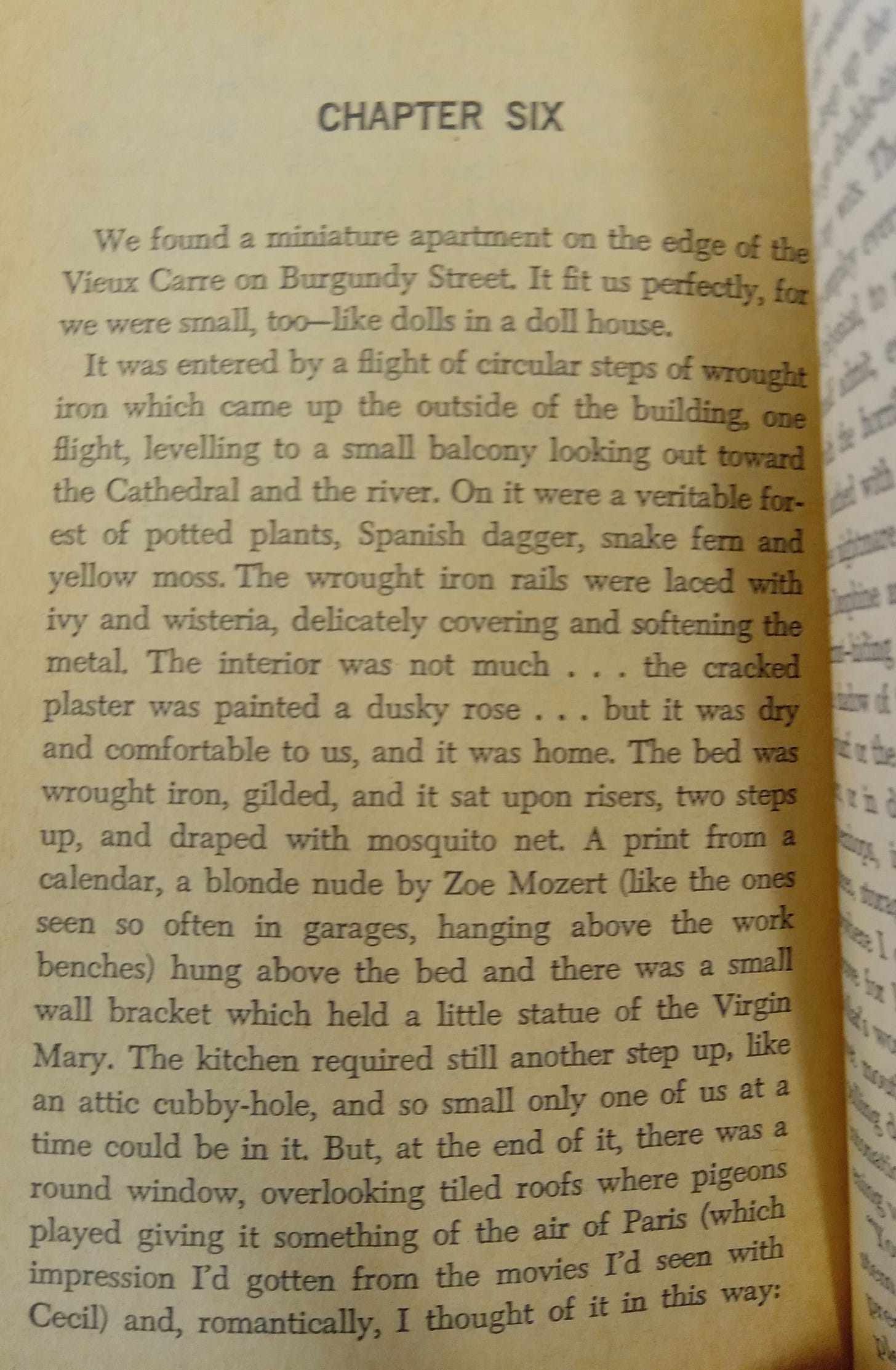

Our protagonists leave the farm, usually, and end up in the gay underworlds of Baton Rouge and New Orleans. It’s sort of Southern Rechy—hustlers, degraded queens, nobody happy or able to connect long with others.

There’s one quasi-domestic coupling scene, although of course it doesn’t work out (most of the novels end tragically—with the idea being that a homosexual is a doomed figure who will be preyed on by hustlers, trade, the police, homophobes, etc, and will end up degrading himself in an impossible search for love—there are basically no gay friendships in this body of work).

Sad!

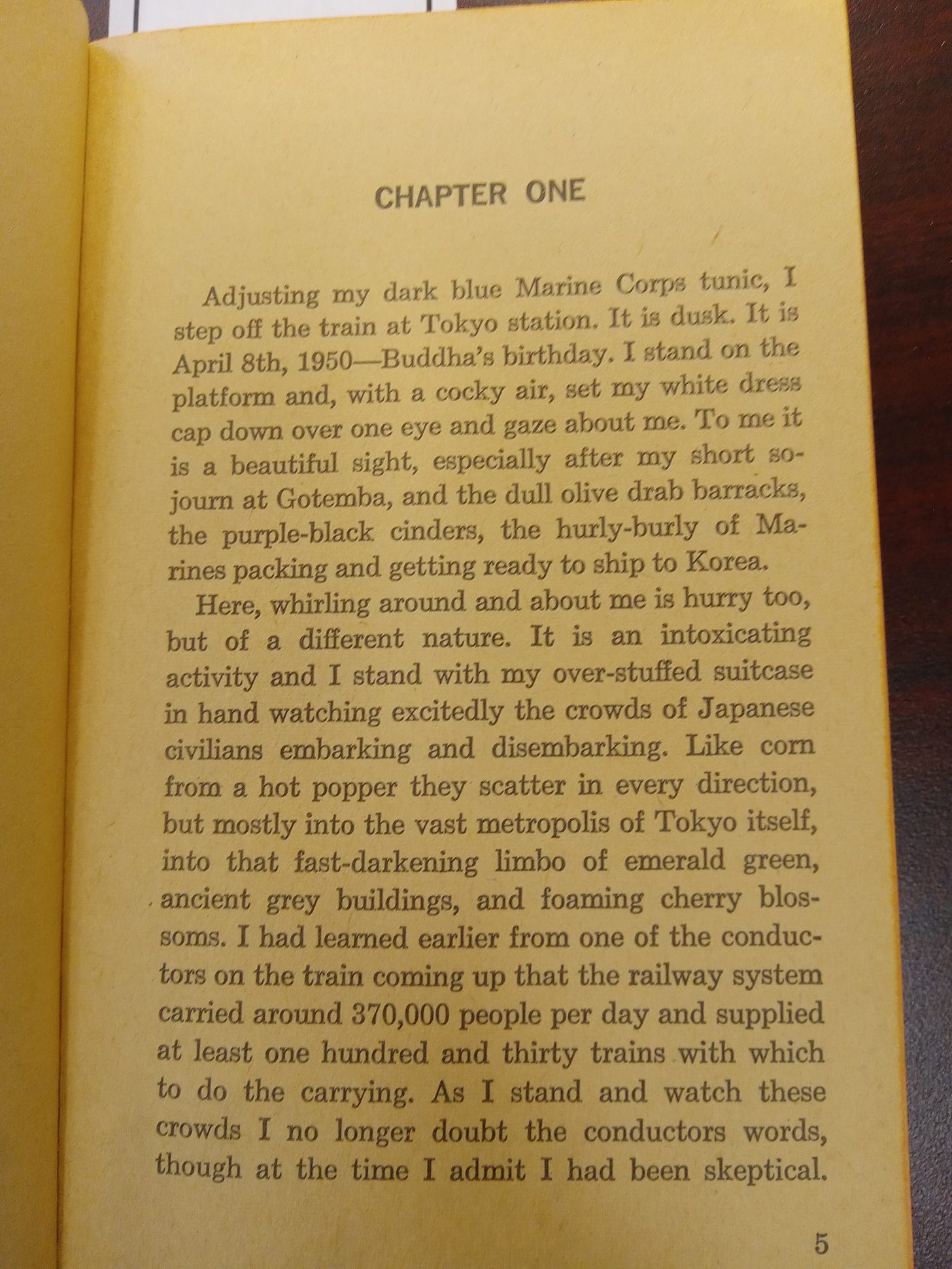

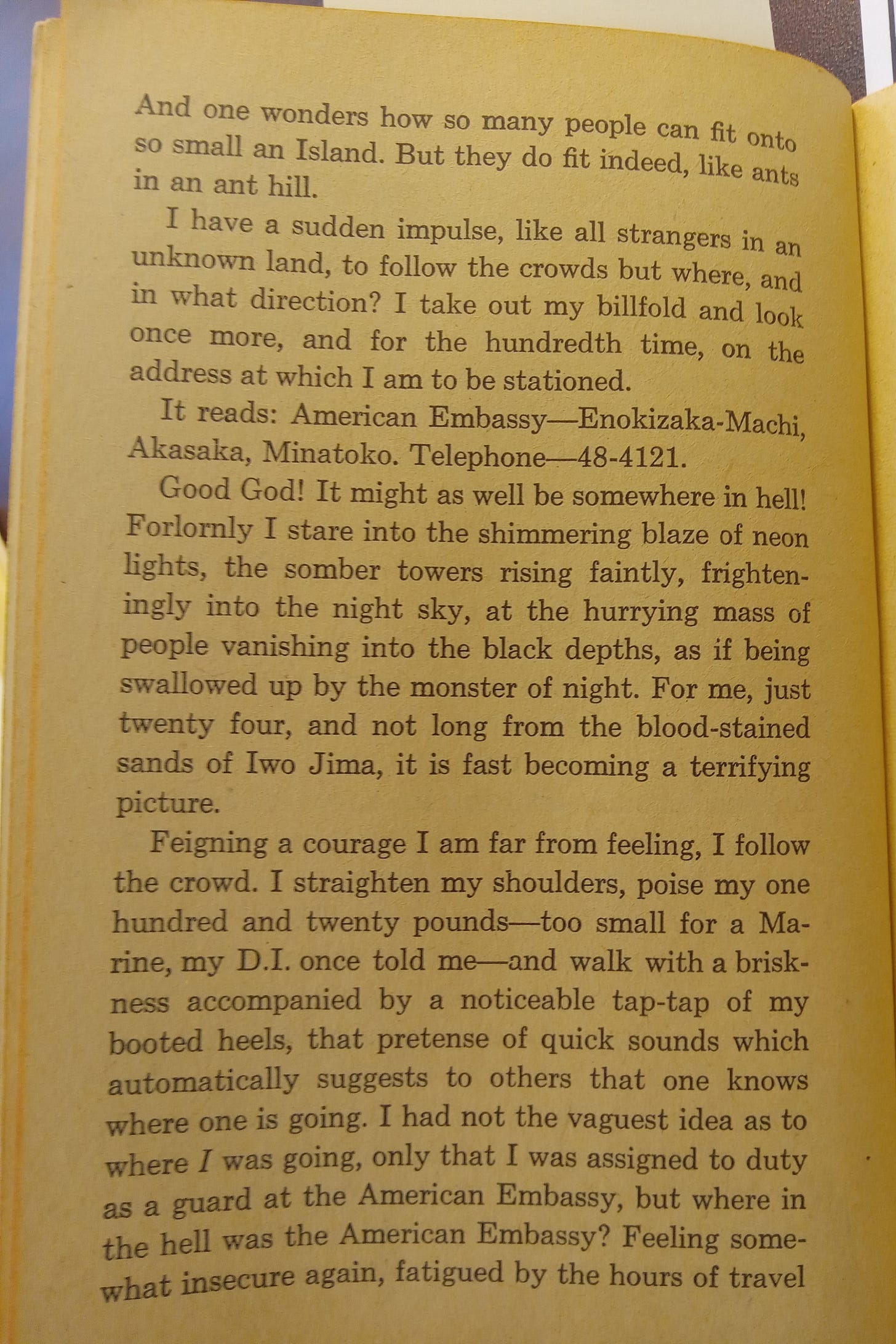

One of the exceptions that proves the rule is a novel set in occupied Japan, about love between a GI and a Japanese man. It starts off as the white guy—who is of course from the South—pursuing the sister, and fending off her brother who hates Americans. But gradually the two men bond (they’ve both lost friends in the war), and the sister conveniently dies allowing them to grieve and bang. Finally, when the GI leaves to go fight in Korea, the Japanese ruefully reflects on his and traditional Japan’s fight in unlikely terms.

Interestingly, this was published the same year (1966) as Sanford Friedman’s Totempole, a more ‘literary’ novel that starts with the Jewish protagonist’s upbringing before taking him to Korea during the war, where he falls in love with a local—and gets fucked by him in some surprisingly graphic scenes (unfortunately for AMWM couples everywhere, it’s not a great book).

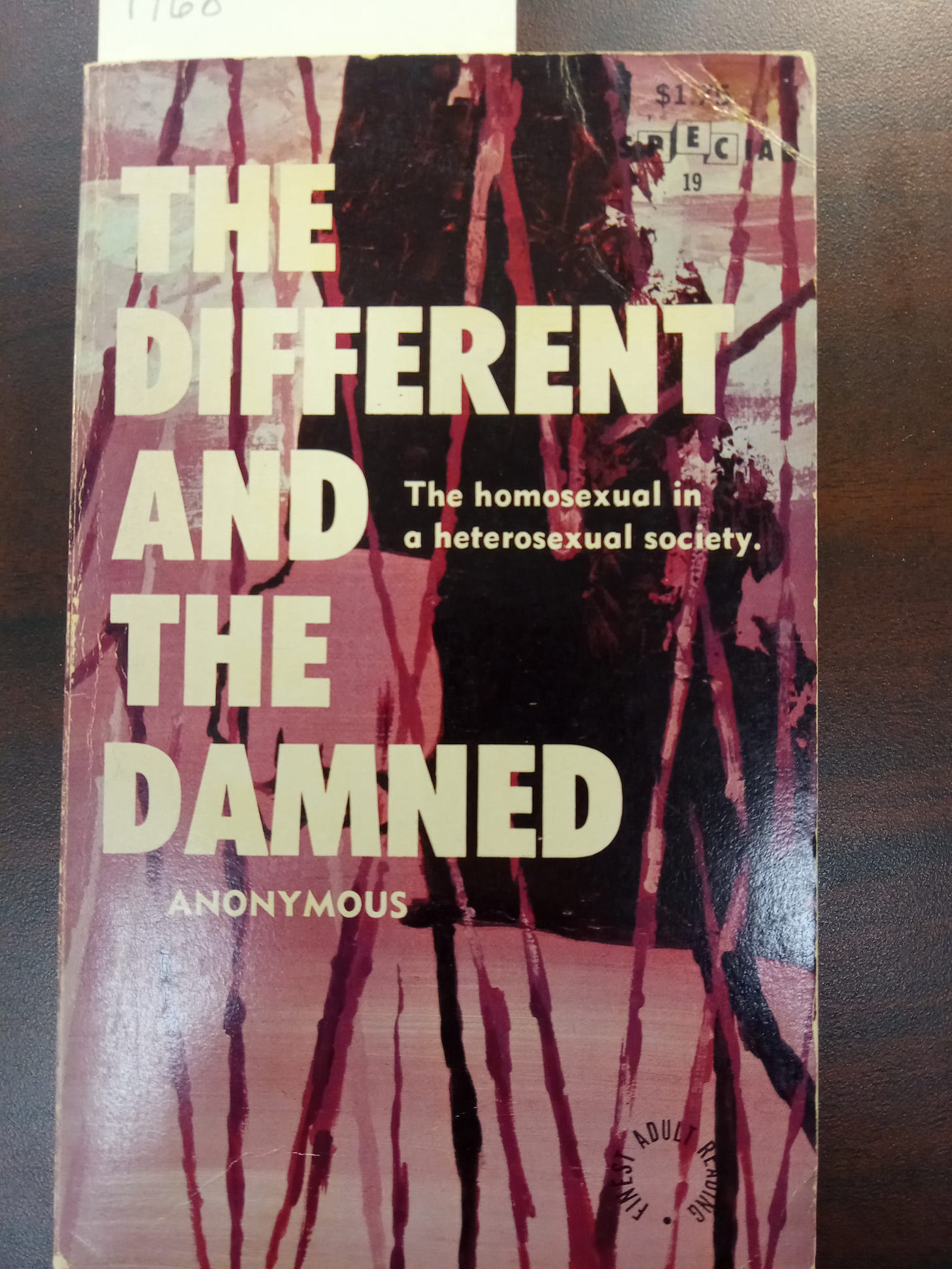

Corley also wrote a non-fiction memoir—which, tellingly, is anonymous, and almost uninterruptedly bleak.

He’s sexually abused, blackmailed, brought to trial, harassed, living his sexuality in fantasies, furtive desperate brief encounters, and humiliating episodes of degradation and exposure—the fiction seems at once to describe these experiences, to eroticize them, and in some moments to escape them, although never into anything like a satisfying gay life with other people (lovers, friends) who support the oppressed protagonist. For example, here’s a scene of him getting raped by his fellow soldiers in the Pacific:

His lover (Shreve) dies, and he returns to an America that, after 1945, is becoming markedly more conservative, homophobic, and persecutory.

And he returns specifically to Mississippi—why?

I wasn’t expecting Corley to be so Southern or (but I repeat myself) so depressing. I suppose it’s good to remember that even the most unsuccessful attempts at literature and the pulpiest pulp can speak from and about a desperate personal and historical situation—which, however hopefully transformed (not that in this moment it feels hopeful), we inherit.

Blake you are slowly drawing me in to this weird project of yours. I don't much like the genre/literary distinction, but you use it to tease out these more or less unconscious imaginations of what is (sexy, sophisticated, admirable, sad, fate, liberation, the list goes on) which begins to be evocative of more than a milieu . . .

I'm not sure what these little portraits add up to, or how you would even show that . . . but the pieces are starting to kind of resonate. I've no idea to what end. This seems to me critical and experimental in a really interesting way. Kudos & onward, I hope.