As part of my ongoing research on the Christopher Street scene (see my various essays on Michael Denneny, an early presence at the magazine and founder of its fellow-traveling line of gay books on the gay imprint of St Martin’s Press, Stonewall Inn Editions) I’ve been reading The New Yorker from the 70s-80s, because that magazine was the target CS’ editorial team sought to emulate.

They wanted to be—and were soon perceived as—“the gay New Yorker,” which was sometimes meant positively and sometimes not. Many of the gay writers of that era wanted to be in The New Yorker— Holleran managed to place an early non-gay short story there at the start of the 70s. But until the mid-80s none of them could get an actually gay story in the magazine (then David Leavitt did it, and everyone in gaylit resented him as a sexless loser sell-out serving domestic comfort fiction to a straight audience—which wasn’t wrong of everyone lol).

The appeal of publishing in CS was thus in part just the negative one that TNY wasn’t going to let you be gay so you might as well write something explicitly gay—and frankly sexual—in a magazine with a much smaller circulation among much less important people but whose readers might, if they liked your work, admire and fuck you (“We can get you laid, even if you’re ugly—and recognized at bars/clubs/etc you want to be seen at” is a powerful allure if an editorial team can really make good on it—although my limited experience, sexual and otherwise, with ‘fans’ readers etc suggests that this sort of thing looks desirable only when you haven’t tried it yet).

And the appeal of TNY as a model to be imitated was, minimally, that it was the most prestigious wide-circulation literary magazine, the best place to place your short story (and maybe your poem), such that being ‘the gay New Yorker’ would mean being the gay magazine gay writers would most want to appear in. But TNY also and I think maybe more importantly was a little world that constituted/reflected a set of people with overlapping tastes, a sort of world CS’ team wanted their own version of.

Obviously, every magazine in some way does this—making/mirroring the world of people who fancy cats, for example. But TNY, at least then, seems to have the combination one would of course desire of being at once quite specific (there is a distinct New Yorker reader, voice, style—a range of products advertised, topics covered, authors published, which is wide enough to live in, at least for a lazy morning or afternoon almost every week, but narrow enough for everything that it contains to have a family resemblance) and respected by the other, larger general world. And TNY’s world is very comfortable—a particular kind of urban person imagined to be upper-middle class, well-informed, open to new aesthetic experiences, sensitive to social problems, continually enrolled in an on-going conversation about issues of important (many many articles begin and run their course along some notion “one hears that people are saying… and yet it could also be said…”—just the tone, with more gentility, of what I suppose must already be put in the past tense as The Way Twitter Was, in which knowing posters offer themselves as neutral-but-engaged observers of the totality of things said).

As I’ve been flipping through them over the course of some months, I’ve sometimes felt a wish to be A New Yorker person who wants to know what’s on at the art galleries (in those days TNY listed every gallery show and every movie playing in the city—and covered the horse races!), because I’m definitely getting out of the house and not staying at home watching King of the Hill or gooning. I’m hip, I’m vibrant! Or I can imagine wanting to be. Just as I can imagine wanting to hear more about that Latin American Boom I’ve been hearing that we’ve all been hearing about, or the crisis in Cyprus (what a shame), c. 1975. The seduction of the sense that one is, and ought to be, keeping up with The Conversation, a real thing that exists, even though you can’t go out into the street and find it , or cash in whatever unseen earnings you imagine accumulate following and anticipating its turns.

The New Yorker, I’m saying, was a sort of community—one that not incidentally had cultural power relative to other communities—and thus might be, understandably, something that another community-in-process might want to copy. Gays of course often think of themselves as something like an ethnic minority, or as part of the coalition of the wretched of the earth (or even worse as ‘just like everyone else’) but contemporary gay identity was produced also by imitating (you could say parodically subverting if you want to be queer about it) the forms by which another sort of community, a community of taste—an implicitly white liberal well-to-do urban set—reproduced itself, in this case without ever naming itself as a community. It’s a consumer demographic, sure, a sociological category, but also an initiation into certain kinds of pleasure, and not without a distinct political sensibility.

This is one of the reasons why I think it’s a mistake to talk about gays either assimilating or resisting assimilation. It’s not a question for gays or any other minority (whether one that already exists or one that is just coming to produce itself as a category/community) of assimilating to a generalized Mainstream—it’s a question of what types, models, forms, etc from the dominant culture are we going to use, are we already using? Certain kinds of mid-century Jews for example became imitation WASPs—and maybe in the end waspier WASPS than the real, vanished ones (see, for example, not just of course oldsters like Lionel Trilling but their present-day imitations-of-imitations like Samuel Goldman crying in First Things about the end of Brooks Brothers!)—while Jewish Shelby Foote played a Delta gentleman on PBS. People are always trying to be something much more specific than just, eg, ‘white’ or ‘straight-acting,’ etc and in the process of trying to become that, they’re often inventing something interestingly else.

CS imitated almost everything about TNY, as if to dispel awareness that getting published in the former wasn’t the same as getting published in the latter. The same not-funny cartoons (although CS’ tend at least to be more, for my money, well-observed, along the lines of “lol gays drink Perrier and eat yogurt,” whereas TNY cartoons then and now have this to me anyway utterly baffling quality of floating at a remove from any particular situation or affect without ever getting excitingly silly—a kind of tepid, weightless, sleepy surrealism that at most elicits a ‘heh’—but maybe I just don’t belong to the social circle of people for whom this kind of humor connects with some real experiences of urban perpetual semi-ironic but unjaded detachment); the same long pieces of reportage where an emissary of the metropole goes out to the provinces (Mexico, Kansas, etc) to report, with a combination of novelistic detail and rather disinterested condescension, on the ways of the natives; the same genially disengaged liberal politics that regards the world’s plights with sincere, vague, short-lived distress; the same ads for luxury vacations, liquors and ornamental crap.

The appeal, I guess, is that to be a reader of the magazine is to be a member of a particular community of taste, one related to New York but not to most New Yorkers—a world of people interested in art, literature, politics and science, but not too interested in anything about them, not ever thrown off kilter and into, say, political extremism, edgy theses, religious fervor, etc.—but also not thrown off kilter by the weird doings at The Kitchen or stories on the Khmer Rouge; nothing that happens can be really disturbing in an existential sense. Almost everything, however, is mildly interesting, seen in the right way, for our sort of people, and worthy of some (but not too much or too excited) comment.

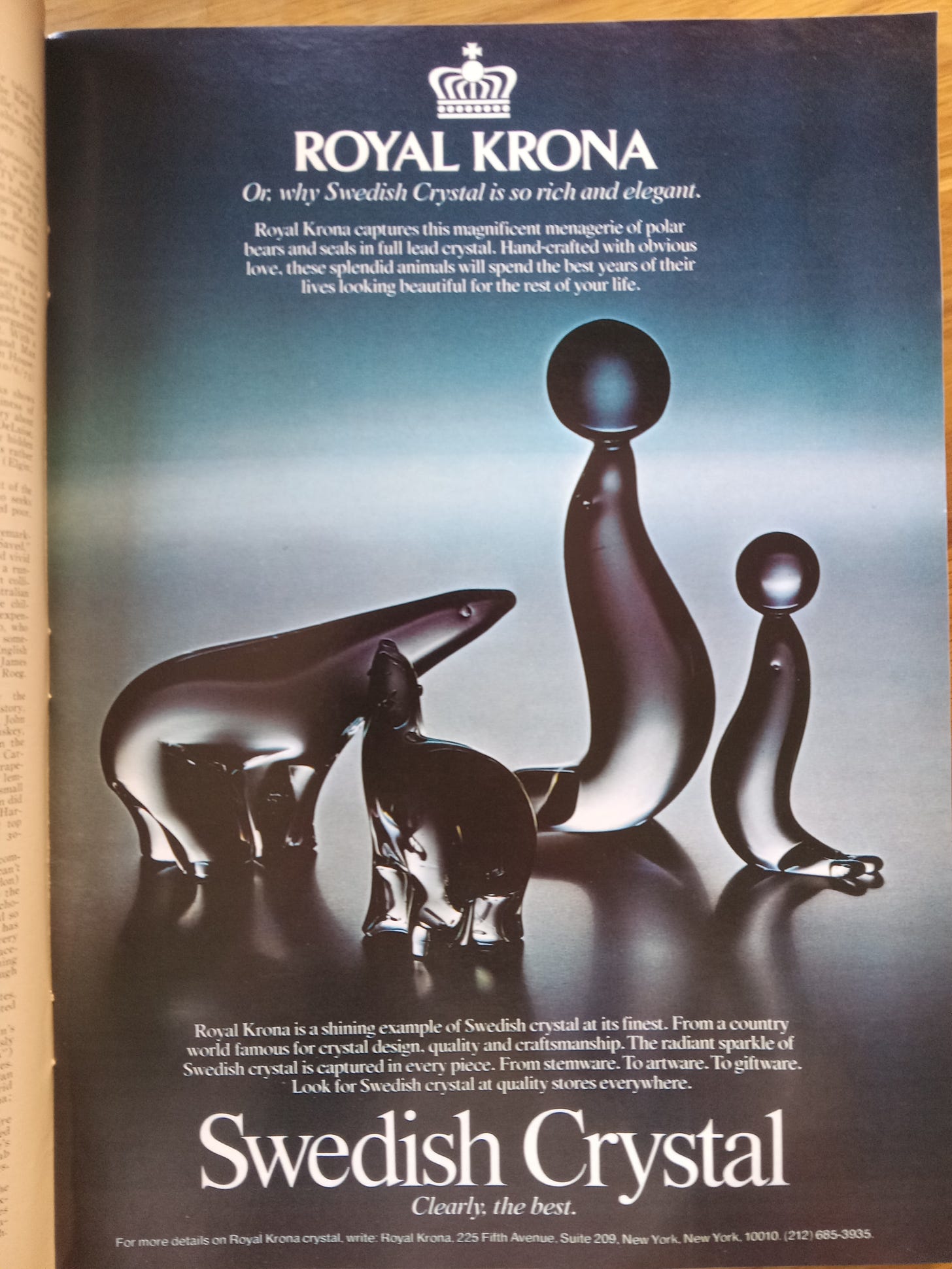

There were, of course, really unhinged people writing in TNY in those years—like Pauline Kael who is working out her psychosexual dramas in her reviews (which often stand hilariously athwart the critical consensus about the movies today—she hated The Shining on moral grounds but loved loved loved Flash Gordon!) as surely as Boyd McDonald in his CS column (reprinted by Semiotexte). And much of the fiction—Borges, Barthelme, Marquez—is wild, inventive stuff that when I first read it as a teenager, in books, struck me as some exalted demanding level of literature that would change, was changing, my life. The poetry includes many competent if not top-shelf cuts from masters like Merrill and Bishop. And yet in the context of the magazine even things by people I like, even things I’d read and admired before, seem unvitalizing and impossible to take seriously—they seem to fit within the same sort of off-beat unimpactful whimsy as the Sempe cartoons, a bit of exotic oddness between some tsk-tsk-ing about Carter’s energy policy and ads for 1000 dollar crystal statues of horses. It’s as though the function of the writer’s wildness were for the reader to reassure himself that he is after all quite sane, on-the-ground, able to chuckle over Kael’s excesses—what a character! Both the content that is soothingly banal and the stuff that is apparently opposite in character seem to work together to produce an over-all effect by which the reader can confront any situation with a remark indicating mild amusement and sophisticated familiarity with just this sort of situation.

Take this issue that has the Renata Adler “Speedboat” the book version of which people seem to have recently rediscovered. In principle the fragmentary, kaleidoscopic play with perspectives and cliches—something also common in the work of Mavis Gallant as it appeared in the magazine—is experimental, as the surrealism of the Latin Americans or Bartheleme is, or the work of Ashbery whom the magazine also much promoted. But it hardly feels experimental reading it on the page with cartoons, ads, and poetry, all of it lowering itself to a common level of ‘oh hm.’

First, the ads that precede it, which are targeted at the very worst people on earth:

Stupid rich people—or rather stupid people who will spend money in order to feel rich—remain the key audience for most surviving periodicals (what keeps the mostly embarrassing Gay Letter afloat?—besides my Substack subscription so I can read the Dick Diaries—Bottega Veneta, which sells products as necessary and affordable and tasteful as crystal seals). Perhaps I ought to be able to say that the things being sold and said in the ads are just there to support the Art or Writing, which is of a different nature, but it’s hard, when you seem them one beside the other, not to look at them with the same eyes.

Here’s some sections of “Speedboat,” which feel, precisely, like flipping half-interestedly through pages of a magazine—is this any different, attentionally, than Tiktok?

The text is cut-up not only by its author’s own methods, but also by inserted poems, cartoons, and—I don’t know the word for this—weird little bloopers where TNY makes fun of dumb stuff printed elsewhere:

The effect of distraction, of paying half-attention simultaneously to many apparently unrelated things held together perhaps on some level by a common vibe or if not that than merely in the blase sensibility of the beholder, is also the effect that produces the sense of belonging to and participating in a particular ‘world’ in which all these things hang together in the taste of someone like ourselves. I want to be ‘for’ the latter and ‘against’ the former—want to be, that is, for an Arendtian sense of taste as world-making in a positive sense, but also for the autonomous, demanding, attention-holding power of the singular work of art, which ought to somehow be sustained rather than suspended by the community of enjoyers. But I find myself resenting that the transgressive potential of experimental literature seems to be belied in such a format.

By the 70s of course the idea of an avant-garde as theorized half-a-century before was already out-of-date—the hope that some new twists to the forms of writing could blast the ruling or oppressed classes into a new consciousness, that they could make us at last intellectually adequate to the dispersals and excesses and lacks of Our Modern Moment and enact the liberatory or annihilating potential of new media technologies thusfar obscured by too-tame cultural productions, that they could do something other than create a sort of minoritarian pleasure for those who had acquired the taste for their mild surprises should have disappeared for good, although it kept and keeps reoccurring in everything from punk rock to new queer cinema to whatever debris of Dimes Square is publishing its shitty first novels.

And I want to say—I have been saying, for example, in my essay on Kristeva—good riddance to the old avant-garde, and, more cautiously, maybe ‘hello, I am experiencing some optimism around you’ to communities of taste instead (although the case against such communities, or at least against imagining that ‘taste’ can make up for the lack of politics or for the necessarily political conditions for even having a capacity for authentic experiences of culture and a capacity of exchange judgments about them with others has been made too in my essays on Arendt’s aesthetics and Dave Hickey’s politics). But I have both a certain sense of historical nostalgia for the era when an avant-garde might have meant something, and for my own adolescent period when a kind of story popular in The New Yorker felt avant-garde to me.

When I was 16 and 17, Donald Bartheleme—who in the period of TNY I’m now reading was perhaps the New Yorker writer—was, if not my favorite author (a position he had to share with people like John Barth, Philip K Dick, and Ayn Rand) then probably the one who most affected me. It was through him—first from reading “A Shower of Gold” in an anthology, then 60 Stories, then Snow White, that I encountered what I didn’t know was the already exhausted theme of The Exhaustion of Meaning. Many of Bartheleme’s stories present language and culture as so much wind-strewn garbage, with our words and thoughts losing their original energy and becoming gummy, sticky, foul-smelling cliches, a thick and blurry barrier between us and actually saying anything.

And yet his own language often and his protagonists sometimes are getting out from or making do enough in the second-hand quality of language that they can express something to the reader if not to another character. At least this was my impression at the time—surely exaggerated both because I was a teenager and because I’d perhaps had special hopes for Literature (I’d already decided religion was a disgusting, evil sham and had to believe I suppose in something). A kind of writing that confronted its own absurdity, always at the risk of disintegrating into the meaninglessness it showed to be the grounding condition of contemporary culture seemed both frightening and heroic, a challenge all the more exciting because Barthelme appeared, often, to confront it and to pose it (to me) with humor—a more exciting, because funnier and lovelier and really gentler, sort of Nietzscheanism.

Now this must have been a mistaken reading of Barthelme whom I haven’t re-read in the past 20 years. But if I had thought that this sort of thing could be the same kind of thing as a crystal seal—as wanting to buy a crystal seal, or even as making fun of the sort of fellow New Yorker reader who would buy a crystal seal—I’d have been even more depressed a teenager than I was anyway.

Ok, well, aesthetics out of the way, now I want to complain about politics. Politics-wise, reading TNY from 1975 has been especially interesting, because you’d think, or I thought, that this would be a year in which New Yorker readers would feel anxious and imperiled. Inter/nationally, there’s the collapse of South Vietnam, which was for most weeks the first item in the initial Talk of the Town section—not, of course, an event that had any direct effect on New Yorker readers, but one that seems to have been taken by the editors as a matter necessitating ashamed comment and the appearance of reflection on this lowpoint of national destiny (it seemed, indeed, not only to people on the right who were furious about it but to people on the center and left who were rather resigned that America was now number 2 militarily and ideologically, that our era of omnipotence was over and had ended in a self-chosen, absurd and wicked defeat—how funny that we could be reenacting that moment a generation later, and then yet again, our decline getting again and again a new fall).

At home, there’s NYC’s financial crisis, with shortages and strikes cutting essential services (garbage, police, firefighting, hospitals) and the easily foreseeable grim future of austerity, inequality and decay looming—people seem to have had, in fact, quite an accurate picture of what the next several years were going to be like, of everything in the city that was going to get worse.

So in a sense, without pushing the comparison into anything unseemly I hope, this is sort of the equivalent of say, the dark sense in, I don’t know, 1982? 83? among the city’s gays that AIDS was going to be not a passing problem but something that would devastate their world. The knowledge that things are bad in the present and not likely to get better soon, that many people are going to suffer, that the government will do little, is indeed pulling back from healthcare specifically and from a broader social compact to care for its citizens. Indeed, gay in the late 70s were—with the handful of first Yuppies and some downtown artists—among the few who could feel amid the broader urban and national economic crisis, the collapse of the old post-war model of growth founded in a broadly egalitarian vision and the transition towards a new openly unequal one, something utopian, a sense of proximate collective future that would be better than the present and could be shaped by and for shared pleasure. Ooops!

But The New Yorker regarded events without alarm. As Saigon was 4 weeks from falling its reporter noted that the restaurants still had all his favorite dishes and the prostitutes on the street were younger and less expensive. As New York tumbled towards bankruptcy the magazine asked if trash really needed to be collected so often—is there really decline? is it such a problem? why are you making a big deal out of this? It often had more to say about how issues were perceived in the media (that is, in part, by the magazine itself) than about the issues themselves, even as it bemoaned that politics was ever more about image-manipulation.

Events at home and abroad tend to become for TNY material for cocktail-party-type remarks that show the speaker to be, he must think, sensitive, aware, drawing connections among diverse phenomena, as in this bit of geopolitical piffle:

We belong to a ‘we’ that is concerned, mildly, about Cyprus, but the situation (which no one understands, to be acknowledged sighingly) reminds us of so many others, we have seen so much of the world and find it really more funny than sad, which reminds me of another story, have you heard the one…

This we—a bit more aggressive, pompous, given to direct assertion rather than ‘it seems to be a fact…’'—is also in the voice of TNY’s leading book critic, George Steiner, who I find a miserable semi-ignorant bully. He presumes to tell us about the state of the we, and to know both what we know and need to know.

The comments on Russian literature—like those on Cyprus and islands above—suggest to me that this ‘we’ is essentially and not accidentally liberal-racist, in the sense that it depends for its own reproduction on the putting in circulation of stereotypes about the Other which are invited to take only semi-seriously—it’s only a bit, of course we know things are more complicated than that, calm down, I’m not saying all islands are like that. This is the shape of non-hateful bien-pensant racism—oh yes, I know the Other, ahah, I know what ‘we think’ what ‘one says’ about him and I know what ‘we think’ and ‘one says’ about that thinking and saying, isn’t it all quite funny and fascinating?

The person who reads this every week, well I don’t know what effect it has, and presumably—I was after all trained as a cultural historian—readers have a lot of agency to shape their unpredictable responses. But the person who reads it is at least invited to become, it strikes me, incapable of either authentic aesthetic engagement or of political seriousness—although such a person I suppose is also comfortably inducted into a community of people who always find something interesting and never disturbing to talk about, some opinion to enjoy considering without letting it wreck their life by becoming a demand from anything outside the limits of their good world.

In that sense New Yorker-verse is a very bad model indeed for a group like gays linked not just by common tastes and consumption patterns in the big city but by specifically erotic experiences (with their always-possible demands that we change our life to pursue, enact, resist, remember etc, the intensity of some particular ravishing beauty) and life-or-death political challenges. But—and I need to think more about this—not only did The New Yorker appeal to the set of gays who set about making a gay world in the 70s and 80s, but it also was a venue for thinkers who influenced them and still speak seriously to me.

Like Harold Rosenberg, who, along with Arendt, was Denneny’s main intellectual influence (they met at UChicago, where Rosenberg and Arendt both briefly taught in the 60s—Denneny edited Rosenberg’s last books of essays and managed his literary estate for a time) and who in the 70s was doing most of his writing/thinking in The New Yorker, with essay-reviews attacking and praising artists and curators and fellow critics, the stakes of these pieces being invariably whether or not the latter were really existential in their approach to art, whether what they were doing was an authentic event—which on the one hand was a very dated sort of 40s critical vocabulary to be using in the 70s, and people knew it, Rosenberg more and more sidelined culturally, a white elephant—and yet his approach and his position was also a great influence not only on Denneny but on the whole cohort of white educated gay men around him, like Ed White, who often talked about gays as if they were the (first or last?) true existentialists, seeing themselves as pioneers of a new kind of freedom (a mode of self-regard distinct from that of the gay left that saw itself as part of the vanguard demolishing norms; this self-interpretation rather stressed that, norms around marriage, family, the meaning of life etc being already abolished for gays, the latter were figuring out how to live in a situation that called neither for conformity nor transgression but invention)—a way of seeing gay life that in some sense made it desperately, tragically, rear-guard (no pun intended) rather than intellectually and culturally forward-looking.

This is part of what makes that moment so interesting to me—that it was truly generative in inventing modern gay life/identity/culture/world, but also in some ways looking very much to the wrong gods, to what was already an unusable past. Then again, The New Yorker itself goes on—with different, scoldier politics, and a lower dumber literary-cultural level, but still, I think (I don’t really read it) not so different in tone, function, etc.

Is it possible to imagine a magazine—any publication, any venue, even lol Substack—that actually discloses a world for us in such a way as to make aesthetic and political life more rather than less urgent, that in its world/community-making qualities builds rather than diminishes our ability to experience as being made on us the claims of, for example, beautiful bodies, dazzling works of art, crises of state, etc, such that our sense of a shared taste with others, of belonging to a set, could help us hear and answer such summons rather than put us to sleep with a drizzle of textual and visual white noise—well certainly it’s possible to imagine it…

Although, in another petulant aside I cut from that possibly forthcoming essay on Harold Bloom, I found myself saying this more pessimistic thing about one of our moment’s (or maybe rather one of what already the previous moment’s) magazines:

This shift could be misread as a movement from a pessimistic liberalism that pretends to respect the aims of the left while privileging the aesthetic and private over the social and political (‘I sympathize with the revolutionaries, but, ah, their dreams of a new world are only ever fulfilled in the occasional works of literary geniuses; there is no collective solution to the personal problem of inventing a life’) to a more aggressive conservatism (‘The police need to break a few heads so I can get back to writing essays in peace!’)—a very common ideological journey undertaken today, for example, by nearly every contributor to Liberties. Bloom, however, militated against politics (meaning, chiefly, against the left—although he certainly had complaints about the grotesque stupidity of the Christian right, and especially its appeals, to the supposed moral lessons of the literary masterworks he praised) not for the sake of post-dogmatic domestic coziness, the freedom to slay surs in one’s own home, to read novels with problematic narrators, to commit genteel sexual harassment (although if we believe Naomi Wolf, he did more than a bit of this) or whatever ‘liberties’ the Liberties crowd seeks to defend.

Lol—of course that’s perhaps nothing but bit of pique about Celeste Marcus not getting back about one of my pitches (although isn’t that, when you think about it, the worst aesthetic-political crime a magazine can commit [against me]?)—but, that pique now expressed, maybe the more productive work of imagination can resume, once, that is, I figure out what really to make of The New Yorker c. 1975—my finger remaining, as ever, on the pulse of yesterday…

Have you read anything by James McCourt? He had some stories published in the New Yorker in the late 70s / early 80s. His later work I think is so close to you in its defense of a specifically gay male culture with its own particular taste and attendant political sensibility (he even has some similar insults to you), but I half suspect you’d find him insufferable